A Conversation with Caleb Caudell

'Hardly Working' is out now

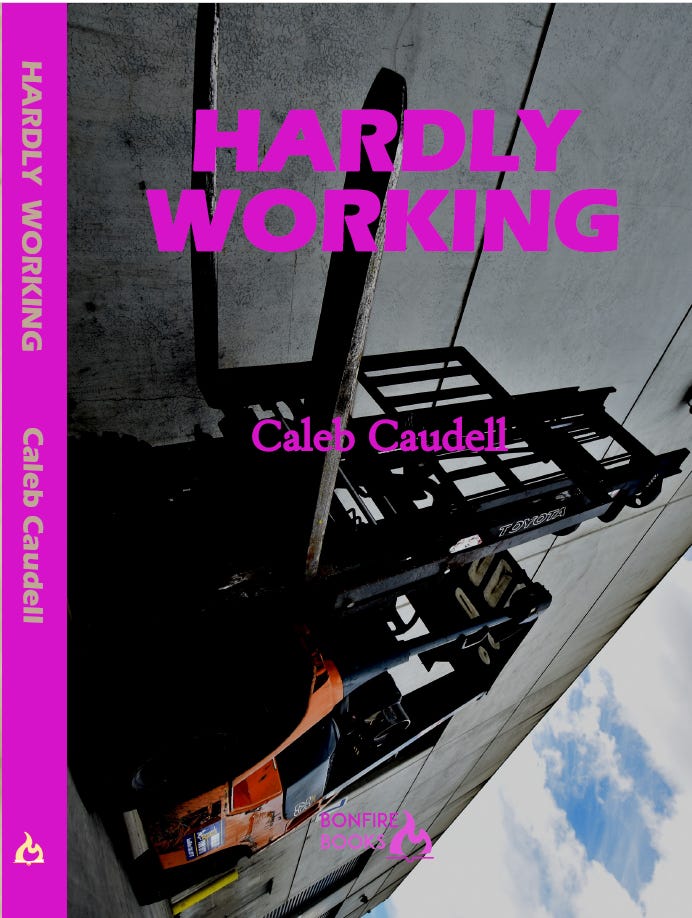

One of the more exciting aspects of 2024, for me personally, was discovering the bounty of new, unheralded writing out there. Ten years ago, perhaps, there was an argument to made that the largest publishers were still elevating the best novelists in this country. If the machine was wheezing, the machine worked. I am not convinced that is true anymore. Editors at the major houses seem to not want to nurture new talent or—more importantly—are not empowered to platform the most innovative, ambitious, and subversive voices. Literary fiction, at the corporate level, has never been less interesting. But that means a whole new generation of sparkling rogues is germinating below. One of them is Caleb Caudell, a writer out of Indianapolis. Though Caudell himself is not a great reader of Henry Miller—he cited, to me, Houellebecq and Delicious Tacos as influences, among others—I saw much of Miller, an early idol of mine, in his profane, witty, and deliriously scatological prose. Hardly Working, his new novel, follows a hilarious and miserable prole on the margins of Indianapolis, working various bullshit jobs to survive. The novel meditates on sexual struggle (including penile surgery), death, and American depravity. “How are you? In a Disneyworld version of hell.”

Below is my conversation with Caudell. For previous conversations with writers working today, go here, here, here, here, here, and here.

What motivates you to write so frankly about sex? Do you think this is missing from contemporary literature?

I wouldn’t say frank writing about sex is missing in contemporary literature. If anything, a stylized or mannered frankness abounds. It doesn’t take much searching to find essays and stories about disappointing affairs, selfish lovers, awkward encounters, and then, on the other end, there’s plenty of writing about the virtues and charms of the erotic life, the quasi transcendence of sexual pleasure, the union of two souls, exploring the body of the other, with all the attendant images of falling rose petals and flickering candle flames and fingernails grazing upward arching stomachs, bucking hips and fire hydrant explosions and soaking wet gossamer garments and bow-legged hobbling to brunch the next morning, as well exhaustive talk on the importance or centrality of sexual interests in the formation of identity and the achievement of happiness.

My view on sex is not that no one talks about it in plain language, or that we still live in an era of repression and must continue to remove the remaining bastions of our puritan heritage. Rather I’m trying to place sex in a larger context and read the current preoccupation with it as a symptom of a much larger scale social and historical transformation, which for the most part I describe in negative and critical terms as a breakdown of social bonds and a decline in the ability to invest in personal relationships and participate in civic organizations and carry legacies and traditions forward. The liberation of sex from repressive social and religious structures follows from the general revolutionary project of human technical mastery of nature; the fruits of which increasingly appear as sterile, solipsistic, anxious, and ultimately self-destructive. What was formerly private (private here being understood as always socially determined, a product of shifting power relations) is imposed on an atomizing public; resources and institutional techniques (developed by the biomedical and psychological industries) are directed toward individualized satisfaction of fetishistic drives and reinforcement of delusions of identity, so that idiosyncratic fulfillment comes to depend on forcing support, compliance, recognition from fractured collectives and other individuals engaged in their own compulsive search for enjoyment or at least homeostasis. In other words, a fearful auto-erotic sadomasochistic war of all against all, shadow boxing fluorescent flesh tube masturbating antagonists in ghoulish mock cooperation.

If anything is missing from contemporary literature, it’s a sharp-edged critical perspective on sex, not necessarily dogmatically prohibitive, but not a pornographic pig trough wallowing in gender fluid slop either (more like gender mud), nor a pseudo-poetic shuffling of hackneyed erotic imagery.

I might have a rarely encountered attitude and write on sex the way I do because I was born impotent, and I’ve had two penile implant surgeries to restore basic sexual functioning. More than most, I was made aware of the artificial nature of sex, its tormenting imperatives that are neither reducible to unchanging biology nor completely arbitrary social signifying systems; I was involuntarily introduced to the links and breakages between sexual identity and the evolving social and technical complexes, and inundated with an isolating shame, a loneliness and inferiority that I couldn’t blame on a prudish morality or my own inexperience or clumsiness. Neither free expression and indulgence of desire nor ironclad repression perfectly solve the problems of sex, but certain moral codes and religious practices seem better equipped to manage our impulses and channel them toward productive and reproducible social patterns.

Do you think a writer gains anything by being steeped in a milieu that is neither East nor West Coast? How did growing up and living in Indiana inform your work and style?

Every writer draws on the particulars of his environment and historical moment. But then what he makes of those givens results from a nature or fate irreducible to time and place. A genius is always worth reading, wherever he’s from; no background, however exotic, can glamorize the trite thoughts of a dullard. From the viewpoint of a reader or scholar, it’s valuable to read writers from different times and places, but quality of mind, for me at least, tends to take precedence over other categories (not that there aren’t places and times with stronger gravitational pulls). There are still these references to place, time and class in my writing, but as far as a public image or brand goes, I’m feeling more and more distant from the obvious identifiers; I’d prefer to be read because of the singular appeal of my mind, and not out of an interest that would more fittingly lead someone to national geographic.

Growing up in Indiana, that could mean many different things; it could mean haymaking and cornhusking, small town shit shooting, flat fields and endless country roads, or it could mean squatting in a burnt-out hovel in Gary or going to prep schools in Carmel. My exact background is Southern Indiana rural/suburban and squarely middle class, so many of the details I put into my work in general can be traced to those settings, but as for how my climate has shaped my artistic inclinations or skills, that’s harder to say, as I’ve long felt somewhat alienated from my surroundings, although without special animus or resentment towards the standard types and scenes of my upbringing. My mom was an English teacher, so maybe a certain fluency with language was instilled by her, but beyond that our tastes and aspirations are divergent. Everyone has their neuroses, but most of my family for generations has been conventionally well adjusted, and though I was acquainted with lower classes and seedier sorts, people with less education, I wasn’t traumatized by exposure to crime and drug abuse.

I don’t know what it’s like to have been born on the lower east side of Manhattan or Echo Park, so I’m not sure if I can say I have certain advantages on account of my origins; it’s likely that I have an advantage over an idiot born in the greatest city in the US, but then if a once in a century talent is born in a port a potty in the hollows of Kentucky, if he ever gets his hands on a typewriter then my comparative sophistication and access to media networks won’t help me compete with him.

We never really know what we’re missing; at the same time we know we’re missing something.

I’m struck by how viscerally you write on the struggles of working-class life—dead-end jobs, cars that don't start, the misery of a lousy rental apartment. How did you decide to incorporate so much of this into your writing?

Mostly for the sake of gallows humor, and to make my own frustrations, humiliations, despair and anguish somewhat bearable. For as dysfunctional, stupid and lazy as I am, if I didn’t write then I’d be an even bigger piece of shit, probably still working the same jobs, just crushing 24 oz beer cans into my forehead all day long, kicking my underfed rottweilers and beating off to Instagram bottle girls. It’s not as if writing is the only thing standing in the way of me becoming Warren Buffet. I’m missing those parts of my brain or soul that help a person take an interest in horseshit or apply himself in a useful fashion. I’ve never cared about anything lucrative and I’m impatient with people I don’t like; at the same time I do like being able to eat and having a place to take a safe private dump, even if my conditions are less than ritzy; the work I do for money is a compromise. I also genuinely enjoy writing, no matter how apparently depressing the subject, and with work and poverty, the material is always right there.

Describe your writing routine. How often do you write fiction and what’s your process?

These days I don’t have an exact routine. I didn’t start writing consistently until I was about thirty, and at that time I was disciplined, though still very modest with the structure. First it was half an hour every other day in the morning after a cup of coffee. Then it was half an hour every day, and you can see where this goes. Soon enough it was an hour a day. When I started writing my first novel it was 1,000 words a day, however long that took, and then when I got about halfway through I was writing 2,000 to 3,000 words a day. It felt natural, I picked up momentum. At the very beginning, before the novel, I was doing slice of life stuff, and also way too much topical internet news commentary, as in “so I just read this article by a jackass....” but I suppose it was all practice; it helped me get into the habit, and it was a good time. Then I tried out some fiction with short stories and built up a little confidence and soon after that I came up with an idea for a novel. As of now, I write when I feel like doing it, which happens to be most days for an hour or two, but it does vary. I have to work, and I might enjoy reading even more than writing, so I make plenty of time for that. And there are the necessary social engagements as well.

I still tend to write best in the morning after some coffee and exercise, I like to run and lift weights, but I’ve been able to write decently in the afternoon and evening too. Whenever I can squeeze it in but I don’t force it. At the same time it’s not that I wait for some surge of inspiration either. It’s just something I do because it usually makes me happy, and if I don’t feel like doing it then I don’t. I don’t make money doing this, my dad isn’t going to disown me if I give it up, and God couldn’t care less either. Come to think of it, my dad and God would probably prefer it if I stopped.

I didn’t write shit for two or three weeks after finishing the latest book; here and there I’ll take a week off, or a few days. Those people who advise you to write every single day no matter what, like they’re SEAL team drill instructors, the whole writing is pain and sacrifice and you gotta strain until the capillaries in your eyes burst onto the page; I’ve always thought that was nuts, and more than a little contrived. I reserve the right to never write another word again at any time for any reason. Even to spite people who like me. Even if I’m under some publishing contract. Hunt me down and throw in me jail. if I don’t feel like writing I’m not going to do it. As for where my ideas come from; if I knew then I wouldn’t have them. It’s another one of those things I really don’t care about; diagramming or programming creativity. If I stop thinking of things I want to write about then I’ll stop writing.

This novel, in some sense, is very much of the U.S. and European autofiction trend, but it’s also quite different, in tone and voice. What do you make of 21st century autofiction and so-called alt lit?

Autofiction is one of those labels that accrues to a narrow selection of works, but then is seen as representative of a general condition, a time. It’s a critical cliche, marginally useful as classification, typically deployed in a more dismissive or grousing manner, and I’d venture to say, more so to distinguish the reviewer/complainer as a person with a taste for more expansive and imaginative writing. Rarely do you hear “I love all this autofiction, what a beautiful trend, I wish everything were written like this” rather it’s another grimace about self-absorption or lack of imagination or class privilege and performative politics, because what tends to be called autofiction is less defined by formal characteristics than it is readily identified by a set of more obviously irritating markers of social class background, political affinities and stylistic traits like flattened affect and simplistic sentence structures. In short, autofiction tends to be equated with credentialed wieners pretending to feel angst about political issues and bumbling through the murk of their half-hearted relationships and spiritlessly exploring their ambivalence with the diction and rhetoric of someone with a recent head injury relearning how to talk.

Twenty-first century autofiction also seems to annoy people because it often features writing about the internet, being online, social media, living in a state of constant distraction, and is overlaid with tedious cultural commentary (in a globalized urbanoid zoomerist patois or an academic robot analytic therapeutic clown speak) already prevalent on the phones everyone uses all the time anyway. It’s sometimes thought that contemporary literature should reflect contemporary experience, reality, the current technological condition, etc., but the trouble is, contemporary technological experience is already defined by the banal ubiquity of reflection, commentary, analysis, quips, everyone everywhere weighing in with their bargain basement Althusserian critique of ideology or their dead eyed sarcastic misreading of some movement or phenomenon. The present reflects itself constantly in the dull shards of innumerable nincompoops and their posts and pieces and updates and threads and clips and streams on all platforms that more and more resemble each other in pumping everyone full of tooth rotting and soul-destroying brain candy; a literary version of this is redundant.

How much should writers care about money? How much should they care about their CV?

Depends on what kind of writer. The less talented you are the more you should care about money. Mastery, producing quality work, providing the world with insight even when you’re surrounded by dimwits, these things are their own reward. For everything else there’s money.

No, it’s a little more complicated than that. Some writing serves a more functional purpose and should be compensated with some consistency. In a better world that I’ve spent the last fifteen seconds imagining, respectable institutions with high standards would pay principled and skilled writers, academics, journalists, for their work. Brilliant minds shouldn’t have to waste their time stocking shelves or waiting tables. But then again, how do we establish these standards? I don’t want to be in charge of deciding any of that. Most of the supposed lofty minds of our time, from nationally recognized best sellers and vaunted intellectuals to all the mini meteoric Substack dilettante debutantes and spastic voluble ventriloquist dummies, with their shirt tucked into their underwear inhaler huffing sensitive nerd affectations and vacuous weepy I’m an alcoholic I was in jail or groped by my uncle and what about the genocide subscription group therapy sessions, seem to me lower than knuckle-dragging, they don’t even seem bipedal. But I make about 500 dollars a year, maybe a little more or less, strictly from writing, and I’ve won zero awards, so maybe there’s something wrong with my judgement.

People thrive in different circumstances; what allows one man to flourish will bring the next man to ruin. Some of us might need poverty, obscurity, censorship, misunderstandings, neglect, to feel sufficiently motivated to do the work only we can do. Others might need a constant supply of maple syrup buckets of praise and love and piles of gold coins to do the backstroke in. As for a CV, I’m still not sure what that is other than a resume. Making sure everyone knows you’ve been published in prestigious journals and magazines? Are there such things anymore?

Who are the writers, living and dead, you admire most?

Dead writers are always my favorite. I aspire to being dead someday myself. Proust is one of the sharpest wits of all time, a beautiful writer who can break your heart even if you don’t agree with his final assessment of love and human relations. Schopenhauer is another major influence, for the brusque clarity and humor of his style and the unsparing nerve of his observations. E.M. Cioran is another aphoristic writer who enthralls me with the brilliant gleam of his darkness, the burlesque comedy of his nihilism.

Fernando Pessoa is also up there for me. Unsurpassed melancholy. Some of the best fragmentary prose poetry. Faulkner is probably my favorite American novelist. I greatly respect the depth and complexity of his characterization and the intricacy and boldness of his formal experiments.

Living writers, I like Houellebecq for his scathing showcase of the devastations of the sexual revolution, his biting and deadpan humor but also his occasional flashes of tenderness. Krasznahorkai is excellent, funny and gothic and baroque, almost an Eastern European Faulkner. And Delicious Tacos is great. His humor is underrated, he’s one of the funniest living writers, but like Houellebecq, he’ll surprise you with his heart from time to time, too.

When you write, what do you feel? Do you need to be in a certain emotional state to write?

When I write, I feel several emotions, though whatever it is, it’s always controlled by a more neutral and more powerful drive to shape the expressions, a command of language, and some need to impress or outdo myself, to feel as if I’ve gone beyond what I thought I could do or what I’ve done in the past, and then that’s combined with a consistent desire to make myself laugh. If I’m feeling sad, what I’m writing will probably be a little sad, if angry, then I’ll go with that, but I’m usually not far from feeling the need for at least a shot of humor, even if it’s bleak or wrathful. I wouldn’t say there’s one distinctive state I need to be in to write; maybe the baseline is best put negatively; not being completely submerged in torpor. Any bit of propulsion in me, I can work with it.

I find it interesting that, for a novelist, many of his influences are non-novelists. I recall another novelist (can't remember who) saying that poets influenced him more than novelists did, because poets were more innovative with language.

This interview caused me to buy the book. But, finding the time to read, it is the problem! Still, it can look at me from the pile and it will know that I want to get to it and that I will as soon as I can.