After Bernie

A conversation with the senator in the Bronx

The last time I was at St. Mary’s Park in the South Bronx, it was 2016. I was twenty-six, trailing along the presidential candidates in the most consequential New York primary anyone could remember. Somehow, both the Republicans and Democrats were contesting a state near the end of the primary calendar; Donald Trump was barreling his way to the GOP nomination, but Ted Cruz and John Kasich still hoped to stop him. This led to all sorts of tableaus we’ll probably never witness again—Cruz, the shrill Texan, wandering into Brighton Beach and Kasich eating himself to death on Arthur Avenue—and it made my reporting life much more entertaining. On the Democratic side, Hillary Clinton couldn’t quite put Bernie Sanders away. He almost won Iowa, won New Hampshire outright, and managed a shock victory in Michigan when most pundits had left him for dead. His path to victory in New York State was exceedingly slim, given Clinton’s time there as a senator and the unstinting support she enjoyed from the Democratic establishment, but Sanders had every reason to contest it. He needed all the delegates he could get. And in certain quarters of the city and beyond, Sanders was undeniably popular. It didn’t hurt that, unlike Clinton, he had actually grown up in New York, in a rent-controlled Brooklyn apartment. He staged one of his campaign rallies in the street outside that very building.

When Sanders came to St. Mary’s, he brought a crowd of almost 20,000 with him. As much as Trump has become the Candidate of Crowds, Sanders could match or exceed him. Around 30,000 came to hear him speak in Washington Square Park. Another rally seemed to bring the Coney Island boardwalk to a standstill. Sanders was, in every sense, a phenomenon, an outgrowth of the mass disaffection young people felt with the political system. Millions of voters didn’t want another Clinton shoved down their throats, especially one who seemed to believe she deserved the nomination by decree. He thundered about free college tuition, free healthcare, and ending oligarch rule. He had a fraught path to the Democratic nomination, even at the peak of his popularity, but his unalloyed leftism held mass appeal. He spoke to economic anxiety without Trump’s xenophobia, and he engaged with race relations, in a conventional sense, well enough. The activist class would force an overt cultural liberalism upon him, but that was for his next, and less successful, presidential campaign. Back then, just about everyone to the left of the Democratic establishment was thrilled to have him and overjoyed at the prospect of a competitive primary. A few dared to dream of a United States president who identified as a democratic socialist—and one who, in Vermont, never formally joined the Democratic Party at all.

Among the delirious attendees of that 2016 Bronx rally was a young Sanders volunteer named Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. There is no AOC without Bernie, no DSA revival without Bernie, and no left-wing of the Democratic Party to celebrate or deride in 2024 without Bernie. If he lacks the oratory genius and world-historical aura of Eugene Debs—if he can never be a political martyr, or the sort of politician who could bring grown men to tears—it can be argued Sanders is the more tangibly influential persona, a sitting senator and two-time presidential candidate who drove closer to the White House than Debs ever did and leaves behind a greater, if battered, infrastructure for leftist politicking. Debs was the hero of the old Socialist Party, which in its heyday elected thousands of local officeholders and sent at least two men, Meyer London and Victor Berger, to Congress. The Socialist Party was undone by the Palmer raids, the revanchist turn against leftist organizing, and the ultimately unbreakable two-party duopoly. Unlike today’s DSA, the Socialist Party ran candidates against the Democratic and Republican machines, and both parties were happy to combine forces to crush socialism, which was most popular with those they deemed suspect: working-class immigrants from Europe. Michael Harrington, the author and activist who founded DSA, had the insight that the only way the left could win in the United States was by running candidates in Democratic primaries. The fact that DSA, much changed from Harrington’s era, has survived and even thrived in the 2020s is a testament to this straightforward concept.

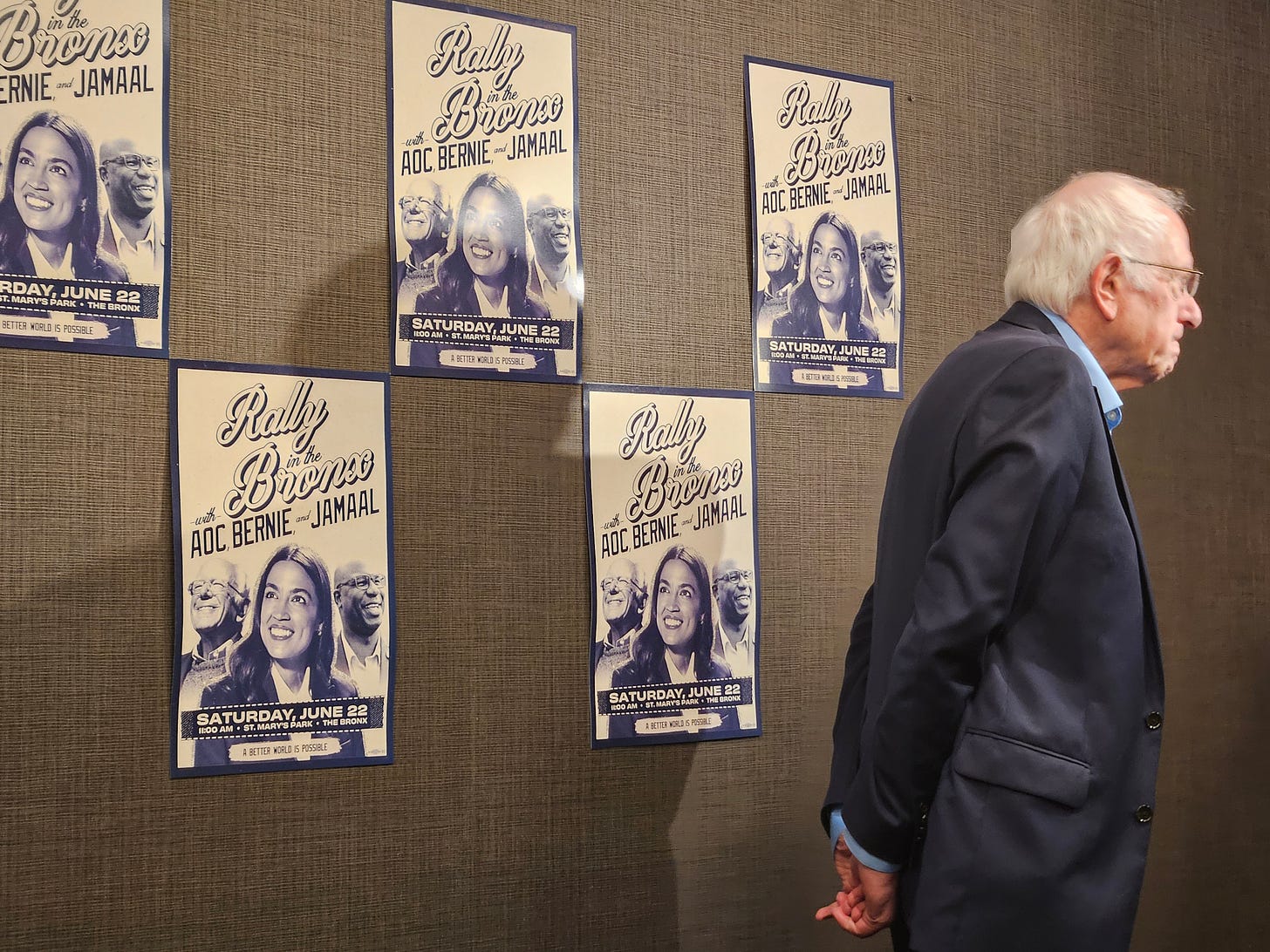

Sanders, the patron saint of DSA—if not a formal member himself—arrived at St. Mary’s Park in the Bronx on Saturday to stump for the endangered Jamaal Bowman. Ocasio-Cortez was the organizer of the rally. In punishing heat, around 1,000 people showed up, a far cry from that raucous night in 2016. Most of the attention was heaped on Bowman for dropping f-bombs, Ocasio-Cortez for dancing to Cardi B, and furious pro-Palestinian, anti-Israel protesters trying to drown them all out. I hovered about and sweated hideously through my dress shirt. There was, thankfully, plenty of free water, and campaign volunteers were hoping to take as many people as possible up to Yonkers, a pivotal city for Bowman just north of the Bronx. St. Mary’s Park, as many noted, is located in neither Bowman nor Ocasio-Cortez’s districts. But it was close enough, and the idea was to have a meeting point where supporters could congregate and the media could film it all.

Before the rally, the Sanders campaign invited a few journalists up to a hotel conference room to interview the 82-year-old senator. The last time I had spoken to Sanders, it was outside a New Hampshire town hall in 2015, so I gladly took the invite to the Opera House Hotel. Sanders came with a couple of aides and seemed largely unchanged from two presidential campaigns; he was still sharp, propulsive, and plenty gruff. It was a reminder of how both Sanders and Donald Trump, another recent Bronx visitor, differ from Joe Biden: age hasn’t altered their speaking patterns all that much. Sanders doesn’t drift, stumble over words, or mangle basic facts. Trump lies and meanders, but he always lied and meandered.

Sanders was almost compulsively on message. I plainly irked him when I asked, right up front, what he thought about the burgeoning anti-Zionism on the left, and the growing number of progressive young people who support a single, binational state for Jews and Palestinians. “It’s not an issue I hear a whole lot. What I hear, overwhelmingly, with maybe very, very few exceptions, is that Hamas is a terrorist organization pledged to destroy Israel and committed an atrocious war crime on Oct. 7. That’s what I hear,” Sanders told me. “Israel has, like any other country, the right to defend itself. But what I also hear is that Netanyahu’s right-wing, racist, extremist government has gone to war against the Palestinian people and according to the ICC—as you know, the International Criminal Court—[Israel] has committed war crimes and they have indicted both Netanyahu and Sinwar for war crimes.”

“Just a very quick follow-up,” I tried again. “I talk to a lot of Jewish activists on the left especially, some do support a multinational, single-state, I just wanted to get your thoughts on that.”

“I’m not really here to go into a great discussion about Israel,” Sanders replied. “I’m here to see that Jamaal Bowman gets re-elected.”

Indeed, Sanders spent most of his time talking about the more than $14 million the American Israel Public Affairs Committee had unloaded against Bowman and how such unprecedented sums warp American democracy. As a writer and journalist, I wanted much more from Sanders, but I understood, at least, his discipline. He was not stepping on any landmines. He is also someone who is going to believe what he wants to believe about young leftists.

If I had more time, I would have asked him about his signature issue, Medicare for All—I asked instead about housing affordability and he told me, unsurprisingly, he’d like the federal government to build public housing again—and how it has faded from the consciousness of the activist class. Few are screaming for it, even as American healthcare remains burdensome and byzantine. Just as Black Lives Matter gave way to Free Palestine, so has Healthcare as a Human Right. In the 2010s, activists could juggle several slogans at once, and it seemed abolishing ICE wouldn’t detract, necessarily, from the fight to establish single-payer healthcare. But Israel Gaza has proved far more totalizing. This, in the long run, is a problem because domestic activism can only do so much to resolve a foreign quagmire and this quagmire is virtually unresolvable. The Democratic Party will grow more skeptical of Israel, but it will be a grinding process. Activists are bound to despair.

Sanders always understood economic motivators. Making healthcare free was about, in part, reducing a cost burden. His successors—Ocasio-Cortez and the rest of the Squad—do not talk much about healthcare anymore. They have popularity and they know how to excite a crowd, but it’s unlikely anyone on the left is currently capable of assembling a national coalition on the scale of what Sanders managed in 2016 or 2020. The political conditions have changed. More importantly, though, few leftist politicians have internalized the lessons Sanders taught, especially when he rose so rapidly in 2016. A winning coalition is a broad coalition. It is knit together around the issues that matter to the greatest number of people. It accounts for those who might fail some of the stricter ideological litmus tests. It is professional, serious, and not held prisoner by online culture. And it is devised, somehow, to seize the Democratic nomination in the manner Sanders, even at his strongest, never could. Sanders, in the Bronx last week, tried his best, hollering about the billionaire class, his voice cutting through the heat. He could only do so much, though, not running for president again—and sans a genuine protégé.

Great piece, Ross! Love your up-close, in-depth coverage.

“It’s not an issue I hear a whole lot." Thanks for asking the tough questions. Sanders is clearly ignorant, blind, or both. He knows his base is the wealthy radicals pillaging college campuses.