Borat's Censorship Quest

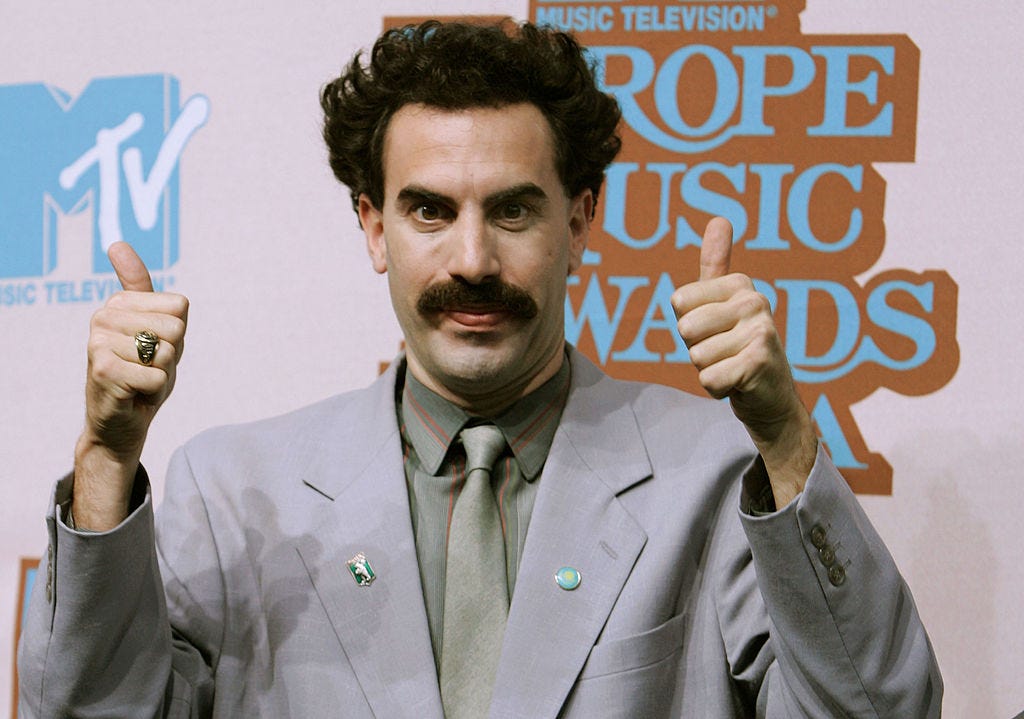

Sacha Baron Cohen's pleas to TikTok

It’s hard to explain, to much younger people, what it was like to be a teenager when Borat crashed into theaters. You have to imagine a nation of high schoolers streaming into cafeterias at lunchtime, their American accents sanded away, broken English tumbling out. My name-a Borat. I like you. I like sex. It’s nice. Great success! Everyone had an impression, and everyone had to share it with you. Undoubtedly, I was honing mine too, because I remember watching the film in 2006 and aching with laughter. Borat, named for the titular character, a bumbling Kazakh journalist who comes to America and films unwitting participants for a mockumentary on life here, vaulted Sacha Baron Cohen to stardom and marked a sort of apotheosis for a style of comedy that no longer finds mass acceptance. The 2000s were the cultural peak for South Park and, for The Simpsons, their final decade of genuine relevance. Chapelle’s Show, another oft-quoted Comedy Central staple, was exploding on high school and college campuses, young boys trying on their Rick Jameses (I’m Rick James, bitch!) and Lil Jons (Yeah!!) and regurgitating all the absurd details of the racial draft. If it all could be alienating to outsiders and expose the talentless—the non-Cohens, the non-Chapelles, the non-Simpsons staff writers—as they endlessly strained to entertain the denizens of dorm rooms and high school blacktops, it was, in retrospect, a golden age for comedy and free expression. The left, generally, was on the side of subversion, and comedy was rewarded for shattering sacred cows. None of these entertainment vehicles contained politics that were so easily discerned—savage mockery mattered, moral instruction did not—and it was possible, in a single episode or film, to find liberals and conservatives coming in for an equal drubbing.

Borat Sagdiyev, played by the Jewish Cohen, is ludicrously sexist and antisemitic. That is part of the fun. He roams America exposing the prejudices of those around him. Borat is shocked women can vote and horses cannot. (He notes that permitting women to vote is like “allowing a monkey to drive a car.”) As for the Jews, they all have devil horns and should be hunted like deer. Most hilariously (or infamously), he leads a country sing-a-long for his song “In My Country There is a Problem” which has, as its chorus, the call to “throw the Jews down the well.” Borat, in Cohen’s Da Ali G Show, is able to get real Arizonans to sing with him, many visibly excited that there is a song that tells them to grab a Jew “by his money” and “by his horns.” Once they throw the Jew down the well, their country can be “free” and they can have a “big party.” Enough Jews, when Borat came out, were aghast, but Cohen’s defense was clear—he was mocking Jew hatred and exposing those who indulge in it.

I, as a Jew, still laugh at this song. I haven’t watched Borat or Da Ali Ga Show in a decade, but I imagine I’d still find them funny. Cohen’s comedy is worthwhile. It also, for a time, inevitably emboldened the sort of shadow antisemites who could cackle at the song just a bit too earnestly. There were, among American teens, enough Christians and Muslims who might have liked the concept of tossing Jews down wells. Or, if not, they could tease the Jew, menace the Jew, impersonate Borat with venom and then retreat into a classic posture—it’s all just a joke. Why don’t you lighten up? This is the price of comedic risk. And if the alternative is censorship—of blocking Borat or any film like it from reaching an audience on the grounds that it’s too obscene—that price must be paid.

Would Cohen feel the same way today? Recently, he joined a group of Jewish celebrities to demand that TikTok police and suppress antisemitic content on the platform. Part of their anger stems from comments (“Hitler was right”) that are obviously antisemitic and appear, apparently, below the videos of Jewish creators. And part of it stems from pro-Palestinian sloganeering they do not like, the kind of rhetoric that has been popularized in the wake of Hamas’ slaughter of 1,200 Israeli civilians and the Israeli government’s retaliatory bombardment, which has killed more than 11,000 Gazans, many of them civilians and children. The actress Debra Messing, according to the New York Times, pressed TikTok to suppress the usage of “from the river to the sea,” which can mean everything from a call for Palestinian liberation to the actual destruction of Israel, depending on who is using the slogan and what their knowledge of Middle Eastern history might be. Cohen himself claimed TikTok was “creating the biggest antisemitic movement since the Nazis” and could “flip a switch” to fix antisemitism on its platform. “If you think back to Oct. 7, the reason why Hamas were able to behead young people and rape women was they were fed images from when they were small kids that led them to hate,” Cohen said in the meeting. All of these claims, with a dose of critical thinking, fall apart rather quickly.