Designed to Fail

The Eric Adams patronage operation does what it's supposed to do

For months, I’ve wondered how exactly things were holding up at one of the most prestigious transportation agencies in the world. Running New York City’s Department of Transportation, with its annual operating budget of $1.1 billion and a capital program 20 times as large, is one of the great ambitions of any urban planner or transit wonk. NYC DOT is not just the biggest transportation agency for any single city in the country. It is where national trends are incubated and the best policy minds can wield direct power, freer of the bureaucratic hurdles that can bog down progress at federal posts.

An energetic and aggressive DOT commissioner in New York can get much done, especially when given a broad mandate by the mayor. Michael Bloomberg named Janette Sadik-Khan, who had held a high-ranking post in the DOT under David Dinkins, to be his transportation commissioner, and she set about transforming the city’s streetscape. Bike lanes, once virtually nonexistent, shot up across the city. Times Square was pedestrianized, boosting tourism there and saving the countless lives of those who no longer had to wade through vehicular traffic. Specialized bus lanes came to the outer boroughs. When Bill de Blasio entered office, he stayed mostly true to Bloomberg’s transportation vision, appointing another renowned transportation expert, Polly Trottenberg, to run DOT. Trottenberg continued bus and bike lane expansions and successfully fought to lower the speed limit on city streets. Her signature program, Vision Zero, curtailed pedestrian deaths for at least several years. She now works under Pete Buttigieg at the federal DOT. Agree or disagree with Trottenberg and Sadik-Khan, it was inarguable that they were serious people with deep backgrounds in the transportation world. DOT had no trouble recruiting engineering and policy talent to New York and retaining them, even with the private sector offering higher salaries.

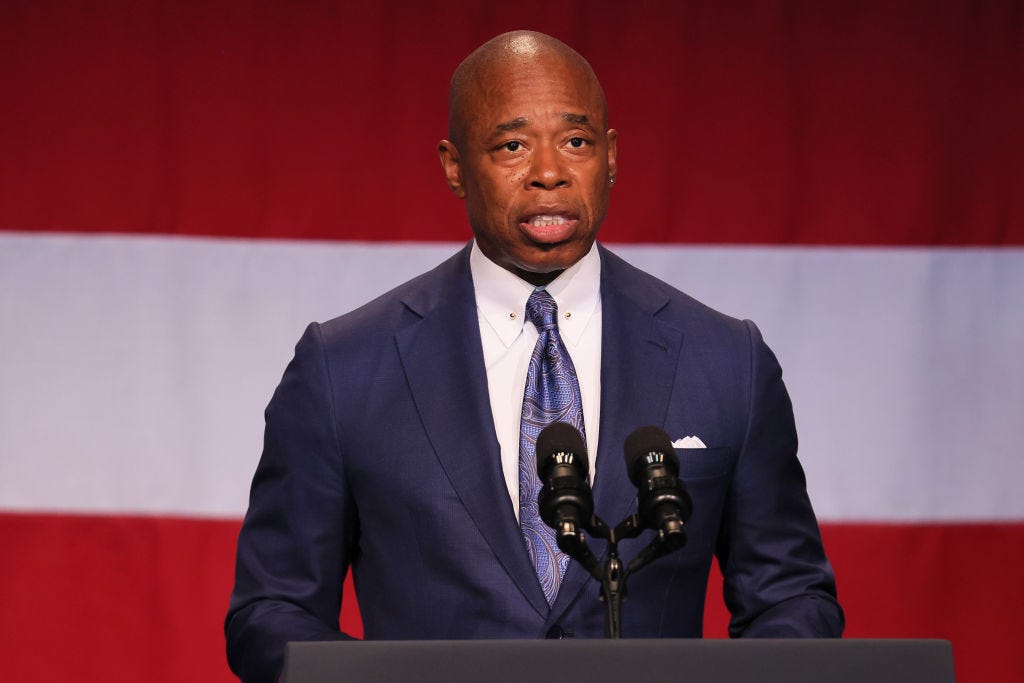

That all radically changed under Eric Adams.