Eric Adams, Unleashed

He is closing in on his dream of becoming the 110th mayor of New York City

There was the mayor of capital, Michael Bloomberg, and the mayor of the multiracial coalition, Bill de Blasio. Perhaps now, with Eric Adams surging to a near-victory in the Democratic primary last night, there will be a mayor of both.

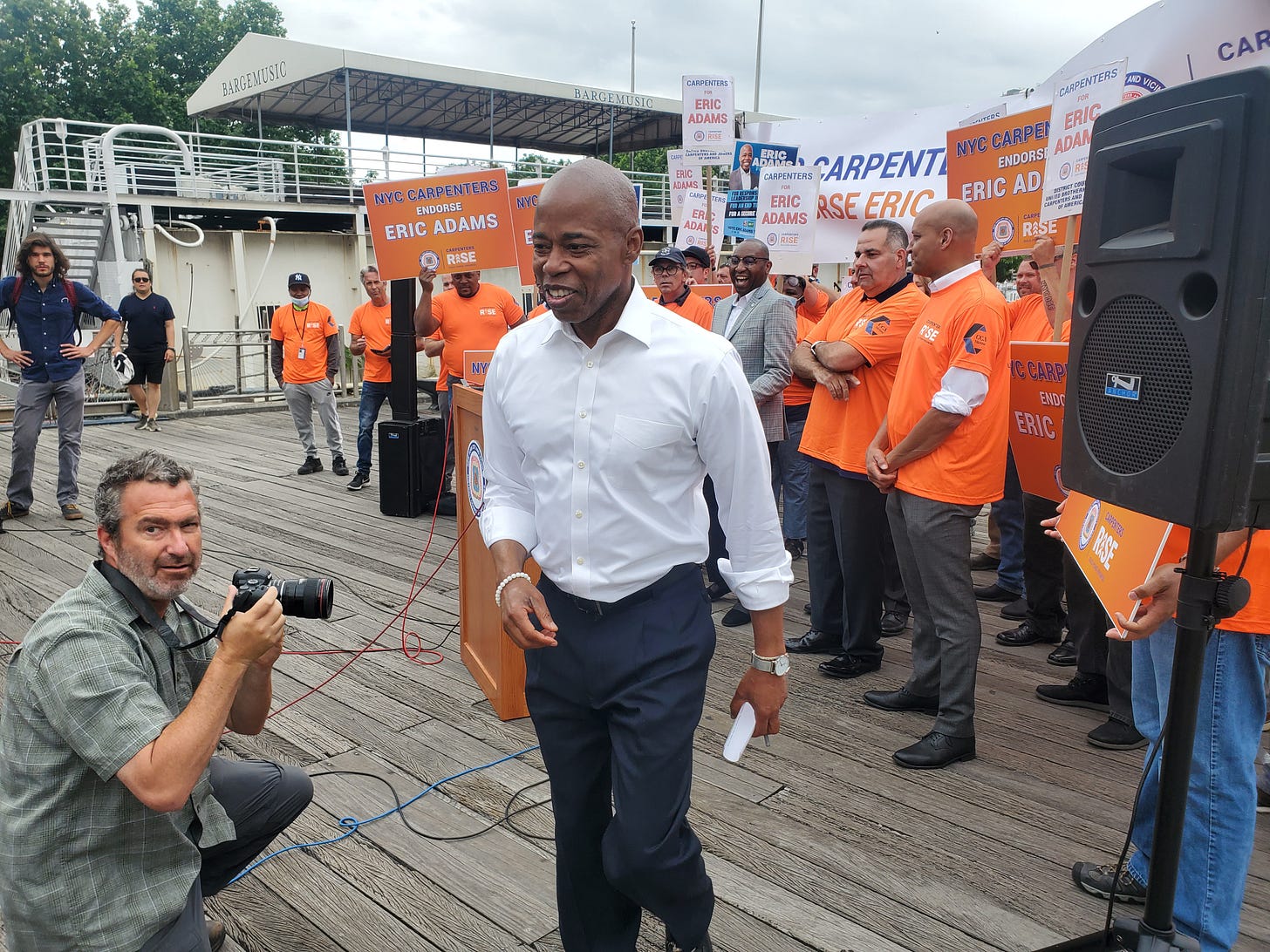

If Adams, the Brooklyn borough president, holds his lead and survives the gauntlet of ranked-choice voting against Maya Wiley and Kathryn Garcia, he will have won a broad victory with a multiracial, working-class coalition. Among first place votes, Adams won every borough except Manhattan. He dominated outer borough Black and Latino neighborhoods. His showing was not as overwhelming as de Blasio’s in 2013—the future mayor won all five boroughs and beat his competition in almost every single assembly district and demographic—but it was, at the minimum, a statement and a demonstration of power.

The billionaire class invested heavily in Adams’ victory. The workers in the outer boroughs, drawn to his history as a police captain and his upbringing in relative poverty and violence, were invested in it, too. For all factions of the Left, as I have written before, this is a damning combination, a marriage of popular will and elite control, the kind of cover the Stephen Rosses and Steven Schwarzmans and Daniel Loebs always craved, and never quite got with de Blasio. A center-left Democrat who did cozy up to plenty of influential real estate developers, de Blasio nevertheless cared enough about the fate of tenants, advocating for rent freezes and granting low-income residents the right to counsel when facing eviction.

None of that really concerns Adams, a landlord with several properties in multiple states under his belt, a man who has cynically framed rent-stabilization as an attack on Black wealth. Unlike the other Democrats who might have become mayor, Adams doesn’t need to heed activists, progressive politicians, the professional left organizations, or the socialists. He can lock them out of Gracie Mansion entirely. And for old, tired foes of progressives in desperate need of new sinecures—Jesse Hamilton, Laurie Cumbo—there may be bright days ahead, indeed.

Adams doesn’t, for now, need the press either. On Tuesday, he barred me and another reporter from his election night celebration at a nightclub in Williamsburg. We had both written tough stories about Adams. His people told us, quite simply, we wouldn’t be let inside. We had no recourse. We both walked off, ending up at Garcia’s party instead. Until then, I had never been barred from any kind of election party or campaign event otherwise open to the public. I was allowed to cover two different Donald Trump election night parties in 2016, one in New Hampshire and one in Florida. Trump regarded the press as the literal enemies of the people. Yet even we were allowed, when it counted, to come in and do our work.

Adams is not interested in letting us—or at least me—do that at all. He feels he can probably pay no penalty for this. Maybe he is right. What do the gripes of a few journalists matter when you have wielded the collective might of the city’s working-class and its oligarchs against your weaker rivals? The message was clear enough: we do not need you, and never will. Bloomberg’s billions insulated him, but he was a businessman Republican in a Democratic city, forced to engage, at least during election time, with his fiercest critics. He could try to purchase a coalition, but had no natural assemblage to fall back on. He did not have Adams’ Bedford-Stuyvesant or Southeast Queens. He did not have the full buy-in of organized labor.

Adams, in his love of the incendiary and his willingness to pick fights, recalls another mayor that he once, a long time ago, appeared to support: Rudy Giuliani. Like Giuliani, Adams is fundamentally a bulldog, freest when he can call his rivals frauds and liars, freest when he is not forced to behave conventionally. Both postured as tough-on-crime executives. Unlike Giuliani, Adams did not ascend on a wave of white ethnic backlash. Instead, he tapped into very real fears that the Left will have to acknowledge: the working-classes of this city are concerned about crime. They hear about the shootings and the murders, or they witness them themselves. Adams always had more credibility on this issue than any other candidate.

In the coming weeks, we will have more clarity. Left-leaning candidates, beyond the mayoralty, may have done quite well, like Brad Lander and Antonio Reynoso. Alvin Bragg, the Manhattan DA contender, may have beat back a wealthy reactionary in Tali Farhadian Weinstein. At least two DSA-endorsed candidates will join the City Council and many socialist-adjacent members could be taking office in the new year. If he indeed becomes mayor, Eric Adams may look back on these days with fondness, when the press scrutiny probably came too late to matter. As mayor, he will not be able to duck behind celebrities like Andrew Yang or hope the pesky journalists sniff around elsewhere. He will be the star, with relentless pressure applied daily. The interest groups will get hungry. The billionaires will want a return on their investment. The working-class may start to make demands. The City Council, unlike in the de Blasio years, will not be in an accommodating mood, and we could very well see the rebirth of the veto-override.

Adams can keep me out of all the press events he wants. But his life is not going to get any easier.

The lack of awareness demonstrated by the Twitterati pundit class in yet another critical Democratic primary is disturbing – I'm sure why I still keep up with very many of them at all beyond there not being too many prestige reporters based in lower-income neighborhoods. For years now it has been obvious that Adams would enter into the primary as an effective incumbent. Leave Park Slope and UWS and talk to business owners, community leaders, etc. particularly in Brooklyn and you will see the lights switch on when you mention Eric Adams by name. The media and Wiley/Garcia/Yang campaigns were either far too slow or far too apathetic to realize that the basic truths of elections still hold fast: they are won on the ground.

Great analysis all election cycle. Hope you write about the city council, which may have undergone an even harder left swing than the senate in 2018. Adams is going to be an interesting mayor, because I think you're correct he won't be moved but as you pointed out he hold a thin coalition against internal (city level) and external (state officials) who'll be pretty aligned against him off the jump. There won't be a honeymoon period for Adams.