Heading Home

On the love of a game

I hit until my hands bled. It didn’t happen often enough to be a marker of fear or rage or grit, rivulets of blood running in the creases of my palms, but I would wait to see when a callous broke, knowing some work had been done. It would be a Saturday or Sunday, winter heavy outside, and I breathed in deep, waiting for the little red light to flick on. Once it was there, I had a vanishing beat to get ready, just enough time for my knees to bend, my fingers to tighten, and my left elbow to rise to the level of my ear, the weight of my teenage body drifting backward, into a gentle coil. The ball, bruised and dimpled, was all I needed. Here it came, exploding, seventy-five, eighty, eighty-five miles an hour, whatever the machine could produce. In my memory, I swing with violence, and smash the ball upward, its parabola broken by the netting of the cage. And here comes another, and another, and another. I was hitting for my life.

In my memory, there is nothing greater than that feeling, a ball struck square, the bat whipping through across my right shoulder. When the light shut off, I hunted in my pocket for the next golden token, each one the price of a round, at least twenty balls. A token was a dollar. This was the only exchange rate that mattered to me. I was fourteen years-old, and godhood was only so far away.

You see, I was going to be a famous ballplayer. What else would I be? Could I be? An adult career produces a narrative that others backfill for you—you write now, so you must have always cared about writing. You talk politics, so politics must have always been of great concern. You have ambition for this or that position, accolade, or trinket—therefore, didn’t the longing reach back to childhood, your little brain scheming for a great big professional class future? No, no, no. I will never want anything again like I wanted, at twelve or thirteen or fourteen, to be a professional baseball player, to ascend to the Major Leagues and prove, finally, this crumpled little life could give way to something enormous. If history is longing on a mass scale, baseball waits at its core, a game played across many thousands of square feet of grass and dirt encircled by the cathedrals of the industrial age. Baseball calls back to the empyrean ambitions of Rome; if it’s too plodding for you, so is prayer or The Birth of Venus. It is both the apotheosis of the team sport—truly, no single player can carry a baseball team to victory—and a contest of individuals, pitcher against batter, fielder against runner, talent and will and luck colliding, in single marvelous bursts, again and again and again. Football is violence condensed, organized in short eruptions over predictable geometry. Once, I cared about it a great deal. But I never wanted to be a football player. I wanted to hit long homeruns into the night. I wanted to race across the yawning expanse of center field, snatching flyballs out of the sky. Before I lost my nerve, I wanted to pitch, game seven of the World Series, blowing fastballs and curveballs by overwhelmed hitters.

Why? I suppose you could say it started with my father, who grew up rooting for the New York Giants and became, in 1962, an original Mets fan. He is one of a shrinking number of living people who has seen games in the Polo Grounds, Ebbets Field, Shea Stadium, and the original Yankee Stadium. My mother, who became a star tennis player on the parks circuit, was raised on Ocean Avenue, mere steps from Ebbets Field, the home of the Brooklyn Dodgers. As a small child, she went with the neighborhood kids to chip out pieces of the famed stadium’s cornerstone as it was set to be demolished. Many years later, when we visited the Baseball Hall of Fame, we found that very same cornerstone in a display case and her youth, in all its glory, flooded right back. My father, being older, is the one who bears the memories of baseball’s “golden age” to me. He was born just in time to see an aging Joe DiMaggio patrol the outfield and looked on, as a young teenager, as Willie Mays, Mickey Mantle, and Duke Snider dominated the city. If you don’t know anyone who can share memories of the period, read the opening chapter to Don DeLillo’s Underworld, which conjures the titanic Polo Grounds on the day Bobby Thomson blasted his “shot heard around the world.”

I suppose, with baseball, there was something primal too. Tennis, in retrospect, was my best sport—had I tried harder, and found the mental stamina to endure the tournament matches, I could’ve reached my potential there. In handball, I found moments of greatness, but that remains a street game, and you’ll never perform in front of millions, no matter how good you get. The dream, naturally, must be circumscribed. Baseball, baseball—yes, I never wanted to be great in anything else. I only wanted to transcend there, to be like the men who, through the genius of their musculature, cracked long line drives over the heads of outfielders. I studied, I practiced, I studied, I practiced. I attacked it all with the discipline of a little samurai.

And I never got to where I needed to be. Not even close.

I was a good baseball player, not a great one. Let’s start there. Goodness, not greatness, hung over me like a vapor. I was small for my age, not terribly fast, not terribly strong. As a Brooklyn kid, I was acutely aware of the borough’s baseball lineage, and longed to join it. Many years before I was born, one neighborhood over, Lafayette High School had graduated another Jewish kid, Sandy Koufax, who for five years transfixed an entire nation with a left arm that seemed gifted by Hashem, or perhaps the pagan gods. I was a Jew, in Bay Ridge, among Irish and Italians, many of them the children of cops, firefighters, and sanitation workers. Many assume, because I’m a Jew who grew up in Brooklyn, I must have been surrounded by my people, but that wasn’t so—often, on my baseball teams, I was the only Jewish player. This brought me neither honor nor shame. I learned to ignore it as much as I could. I certainly suited up for church teams: St. Patrick’s, St. Francis Xavier, St. Bernadette’s. Still, though, I wanted to prove what a motivated Jew could do.

Looking back, I remember the intensity of those years. I loved baseball, and with this love came anguish. Games, in my own mind, became freighted with enormous import. It could be a Wednesday in April, a Saturday in June, nowhere near the playoffs. Every at bat, every pitch from the mound, and every ground ball required inordinate precision. In every moment on the field, I had to reach—and then surpass—my own potential. There was no other way to be in the Major Leagues. What defined my play was not so much the anticipation of success but the absolute fear of failure, a fear that could swell and overtake me with startling ease. One poor at bat would define the next. If I couldn’t get a hit in the third inning, how could I get a hit in the sixth? If I went hitless today, how was I possibly going to hit tomorrow? I waited for my body to fail me. Inevitably, it did—because no sport in the world, perhaps, is more defined by failure. When Ted Williams, in 1941, became the last man in hit .400, he still could not get a hit in almost 60 percent of his at bats. I told myself to internalize lessons like these, but I never did. I certainly read Williams’ Science of Hitting many times, cover to cover.

What was I good at, really? I was best at not striking out. Hand-eye coordination was my only real gift, what I inherited from my mother and sought to enhance through many hours at the batting cages. This skill was fed further by my overriding fear. Nothing could embarrass me more than swinging and missing at a pitch. So I did so as little as possible. I recall, playing for a 68th Precinct team when I was ten, passing a whole year without striking out once. What a point of pride. I wanted to hit for power, but there was no way I was ever going to swing hard enough to not put a baseball in play. If I could groundout or fly out, I’d save face. A single or double, of course, was better. The other quirk of my early years is that I managed to play baseball both left-handed and right-handed. I was naturally ambidextrous, writing left-handed while learning to play tennis right-handed. Through the age of eight, I was a right-handed pitcher and third baseman in little league. I decided, at around nine, I liked hitting left-handed and didn’t mind throwing that way, either. Some of the greatest baseball players of all-time are lefties—Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, the aforementioned Koufax—and I felt a kinship with this privileged minority. I gave up third base and became a first baseman and outfielder, fairly seamlessly. I pitched too. I liked throwing curveballs. One time, at least, I was mentioned in the local newspaper, the Home Reporter, for throwing a shutout.

Competitive baseball in Brooklyn could be peculiar, amusing, and occasionally vicious. I never played with one team for too long. In certain summers, I could even play for two or three, what were known as “sandlot” or travel teams, even if the travel was limited to the Tri-State. At the Parkville Youth Organization, coaches told me, in wondrous Brooklynese, to “trow da ball.” In that same league, umpires ran out of baseballs and parents first fought in the stands. As a ten-year-old, playing for the Dyker Heights Knights—nifty purple and black uniforms—I stole second base and was furiously told, by my coach, how incompetent was. Did you get the steal sign? I did not, I told him. I just stole the base. You only run when I tell you to run. On this same team, a year later, I witnessed physical pain of the kind I had never known before. An opposing player slid hard into Vinny, our third baseman, and he instantly shattered his leg. He screamed and screamed until an ambulance arrived. I still see him, two decades later, writhing on the ground. We were around Calvert Vaux Park, at a field we all called Bug Stadium because of the fat mosquitoes that would hang in the air come summer. Bug Stadium’s infield was virtually gravel. My right knee bled any time I slid hard. That summer, or one near it, I got a terrible sunburn at the beach and pitched a no-hitter later that evening.

Bahkan. That’s how a good Brooklyn coach would say my name, with either approval or fury. Bahkan, get over heah. I probably had the most fun in the Kiwanis League, a wood bat league made up of topflight teams from around the borough. This was the era when wood bats were making a comeback—aluminum had dominated the 90s, but aluminum was now regarded, by some, as too dangerous—and I hunted out a bat made of bamboo that was supposed to offer a little extra pop. The teams tended to be segregated by race and ethnicity. Our squad, Bay Ridge baseball (later the Bombers), was mostly Irish and Italian, though we had a few Puerto Ricans as well, including my childhood best friend, Lawson. Youth Service League, where a young Manny Ramirez once played, was mostly Hispanic. The Bonnies were the power of Black baseball, boasting alumni like C.B. Bucknor, the longtime MLB umpire. Games among the teams were competitive but not contentious; my rage, chiefly, was saved for myself, especially if I struck out. When I was fifteen, our Bay Ridge coach made us go “canning,” which meant standing at the side of a road with a bucket asking drivers for cash. We were raising money for a tournament in Allentown, Pennsylvania. Already a bit snide, I angered my coach when I said canning should really be called “begging” and joked he really just wanted the cash for a new radio in his car. Whether this was true or not, we never went to the tournament in Allentown.

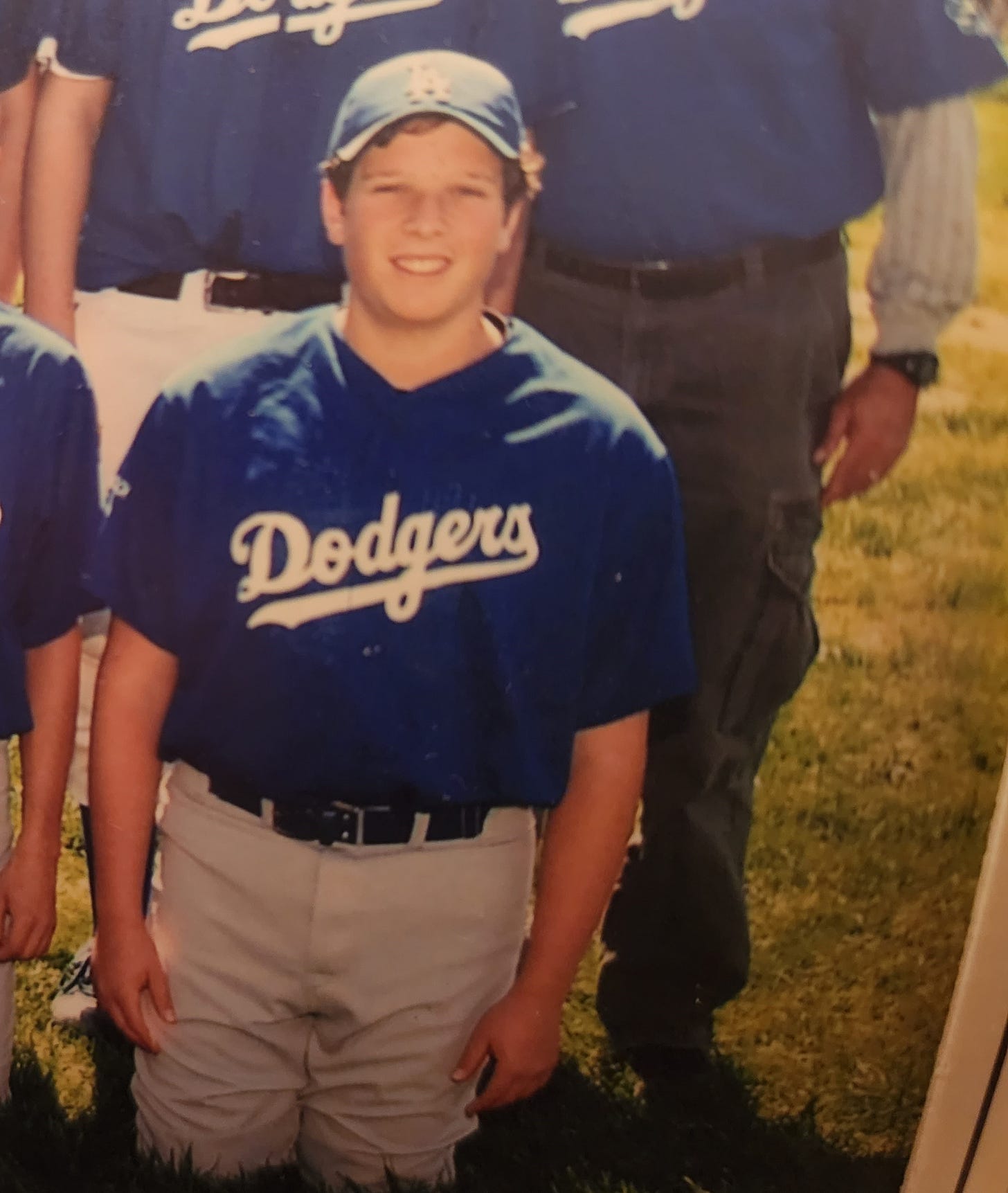

The next year, I was on St. Patrick’s, along with some other teammates who had made the jump from Bay Ridge, a league that always seemed on shaky fiscal footing. One day at the end of July, between games of a doubleheader, a teammate put a used condom he found on the floor of the dugout in my glove. When I discovered it, I knocked his cap off and stomped on it with my cleat. He punched me on the side of my head, I punched back, and we were in a scrum, two chubby red-face boys. We were kicked out of the game and told to go home. That was the same summer Italy won the World Cup. I know this because Sal, one of the boisterous Italians, brought an enormous Italia flag to the games and hung it over our dugout. A year later, 2007, was the last full summer of baseball I ever played. I was seventeen, about to head to college, and knew by then I would never be a professional. I was playing for St. Francis Xavier in Prospect Park, for a team called the Dodgers. Lawson, a great pitcher and third baseman, was there too. We reached the championship game, falling to a team with a very strong left-handed pitcher I was proud, at least, to single off of. What I recall most, of that time, was taking a lead off third base and not stealing home after a ball got past the catcher. My coach yelled at me to go, go, go, and I didn’t think I could make it. The batter at the plate eventually struck out and the inning was over. As I was heading out to right field, my coach continued to chide me for not listening, for always doing what I wanted to do on the field. Fair enough. Crackling with that familiar rage, I turned my back to him and jogged out, holding up my left hand in the air, my middle finger extended. My coach yelled that I was out of the game. We only had nine players and this would mean a two man outfield. He didn’t care. Teammates begged for him to reconsider, mostly because we would be doomed if we had two players covering an entire outfield. My behavior wasn’t defensible; they just didn’t want to lose. Eventually, I was sent back out.

Baseball, the game I loved, was where I first understood human limitations—the ceiling of a dream, the prison of genetics. I was not going to throw a ball ninety miles per hour. I was not going to hit, with any regularity, a ball thrown ninety miles per hour. The last time I believed I was headed to the Big Leagues, I was fourteen. I was taking hitting and pitching lessons with a former scout and minor league pitcher who coached at my high school, Poly Prep. He was a marvel; then in his early seventies, he still could throw a baseball his age (or faster) and had a knuckle-curve to truly flummox the kids like me who took lessons from him weekly. A left-handed pitcher, he smacked fungos right-handed with a real fungo bat—much narrower than a bat typically used in games—and seemed to delight in trying to drive flyballs over the outfielder’s head. He taught me how to scoop balls out of the dirt at first base. I needed soft hands, he said. Like caressing a girl. I pretended to know what he was talking about.

My heart was in summer ball, but I wanted to make varsity as a freshman. My school was quickly becoming a baseball powerhouse and it was clear, early on, this was never going to happen. The kind of kid who did play varsity his freshman year, Kevin Heller, ended up getting drafted and playing in the Boston Red Sox organization. The son of John Franco, the Mets fan favorite, also ended up at my school, and this meant occasional appearances at practices from the pitcher himself. My personal brush with Franco was when he told me, as I was warming up in the gym, that I had a lazy throwing motion and should raise my shoulder more. But I patronized his business repeatedly: for a long time, he and his brother owned a batting cage and arcade in Sunset Park, where I went almost every single weekend to hit balls off the machine and play Marvel v. Capcom 2 or NFL Blitz. I had a tradition of holding birthday parties there which continued into my freshman year of college. We’d play dodgeball on the basketball court and then devour pizza pies. It was John Franco’s, as we called the batting cage, where I understood what I was up against. Heller, an affable kid, smashed ball after ball, never missing. What was a relative struggle for me—to meet every single ball square, to not foul one off or swing over it all together—was as simple for him as breathing. He was superior, much superior. I was not going to catch up.

The final blow was freshman year, traveling with the J.V. squad to spring training in Florida. We stayed in a hotel at Fort Pierce. I remember the coach waking us up before six a.m. to eat at Golden Corral, and making us run drills all day in the unrelenting sun. We’d crowd into vans, with the hits of the spring inevitably blaring through the speakers. “Yeah!” is fully imprinted now and I can’t hear it, nearly two decades later, without thinking of those early morning van rides, sweat rolling down my forehead. One evening, we were taken to a Wendy’s and told, less than an hour later, to run wind sprints. I vomited. What I at least could look forward to were the games; I had trained all winter to be a star, and here I would show my disinterested teammates my potential. Long doubles, maybe a homerun. The coaches couldn’t ignore me.

Eagerness, though, quickly gave way to terror. I couldn’t fail, and therefore I would. I struck out. In the next game, I struck out twice. The second time, hot tears burned in my eyes. I hate it here.

I stuck to the aforementioned summer leagues. After tenth grade, I made tennis my varsity sport, since both tennis and baseball were played in the spring. My senior year, the varsity baseball team had an undefeated season. They certainly never needed me. My college, Stony Brook University, wouldn’t require my services either. A Division I school, Stony Brook had developed the best baseball program in the area. Future Met Travis Jankowski was on campus with me, along with Nick Tropeano, and the team reached the College World Series the year after I graduated. By then, I had become a full-time softball player, and I found I was simply better there because the sport was, at least on the level I played, not as challenging. I spent several years playing in a slowpitch Long Island league before switching to the fastpitch league in Brooklyn that still swallows up my Sunday mornings. We’ve reached the semi-finals the last two seasons. We better win it all this year.

Off the field, I obsessed over baseball history and statistics like a Hebrew scholar would pick through the Talmud. As a math student, I was worthless, but if an on base percentage or OPS+ was involved, suddenly numbers made sense. Before the world knew Nate Silver as Nate Silver, I knew him as one of the young writers at Baseball Prospectus, which I read with some regularity, straining and failing to understand how PECOTA really worked. If I wasn’t going to be a professional baseball player, I could settle for the front office as the next Yankees general manager. An easy fallback. Though my father remains a Mets fan, he always took my Yankee fandom in stride. Perhaps, I wonder, because he helped make it happen, taking me as a small child to the 1996 Yankees ticker tape parade. I was addicted after that.

Millenial Yankee fans grew up with absurd expectations that were typically met. Imagine, as an eight year-old, watching your team win 114 games and the World Series. Imagine a World Series victory the next year. And the year after that. Those were the boom years of the late 1990s, all I really cared about. I collected the official World Series caps, each with a unique patch. I sauntered around in the Yankee team jacket. I piled up the navy blue player t-shirts and wore them until little holes invariably opened up in the armpits. I can’t tell you how many shirts I had, how many pieces of memorabilia, how many cards. I bore, inside of me, the past and present of the game. I remember, randomly, shocking an adult fan when I knew, from memory, the career batting average of Frank Thomas, the White Sox star batting at the old Yankee Stadium. Bored, later on, in an eighth grade history class, I made a complete sketch of what I hoped would be my own career statistics in the Major Leagues. I went year by year, inventing a baseball card. In the far-off future of the 2010s and 2020s, everyone would know me.

History, as a school subject, did hold appeal for me, and it was how I came to embrace baseball in full. It is not, decidedly, America’s pastime—the NFL has been more popular since at least the 1990s—but it does define and mirror the nation’s history more than any other professional sport. Baseball has been played since the Civil War, and professional leagues in major cities were building followings by the 1870s and 1880s. “Modern” baseball began in 1901, with the formation of the American League, and the first World Series between the American and National Leagues was played in 1903. Baseball, then, was a sport of ruffians, of the Irish and German working-classes. Following the collapse of Reconstruction and the rise of Jim Crow, baseball became segregated by the dawn of the twentieth century, with Blacks forced to play in their own leagues. One of baseball’s first heroes was a college-educated WASP, Christy Mathewson, who pitched for the Giants and brought “respectability” to a sport that the elites believed it desperately craved. It was an era of rampant of fighting and gambling. One of the great throwers of games was an elegant first baseman named Hal Chase. Were it not for the Black Sox, he’d be more famous today. (I can write this history without looking any of it up. One of my old parlor tricks is reciting every single World Series matchup from the 1940s until the present day from memory.)

The rise of baseball followed, or anticipated, the explosion of the world’s industrial power, the arrival of modernity. In 1919, the year the White Sox took money from gamblers to lose, on purpose, the World Series, a young pitcher from the Boston Red Sox named Babe Ruth hit 29 homeruns while playing, part-time, in the outfield. The teammate with the most homeruns after him was Harry Hooper, who hit three. Until the arrival of Ruth, baseball had been an “inside” game of bunts, chopped singles, and stolen bases, with the rare homerun tossed in, sometimes of the type that simply went over the outfielder’s head and rolled around in the deep grass. This was called deadball. The most dominant figure of this period had been Ty Cobb, a ruthless genius purported to have sharpened his cleats so he could inflict maximum damage on the basepaths. Cobb played with a grim fury; he was detested by his teammates and accepted by fans only because he was so much better than everyone else who took the field.

Ruth was something else. An orphan from Baltimore, he reveled in his budding celebrity. He was known for his enormous appetites—food, women, alcohol—and performed physical feats on the field no one had seen before. He was a revolution, like Pablo Picasso in the arts or Chuck Berry in music. Ruth’s swing was distinctly modern. He hit with a pronounced upper cut, his large body coiling and then whipping across the plate, the ball leaping off his heavy bat in a high arc. He tried to hit homeruns and did so with an ease that was, at the time, unfathomable. Sold to the Yankees, Ruth inaugurated a new dynasty and a style of baseball that came, just in time, for the birth of a mass culture. In 1920, Ruth hit 54 homeruns, more than every other team in the American League. This was the dawn of the “live ball” era. With a new type of tighter-wound ball introduced, along with the gradual abolition of the spitball, baseball became a game of power, with homeruns soaring as other sluggers eventually tried to match Ruth, including Lou Gehrig, Jimmie Foxx, Mel Ott, and Hank Greenberg. Batting averages rose as well. Rogers Hornsby, a second baseman who possessed all of Cobb’s talent and even more of his misanthropy, managed a .400 average three times in the 1920s.

Black players, meanwhile, starred in the Negro Leagues. Segregation was enforced by the racist commissioner revered for driving gambling out of baseball, Kenesaw Mountain Landis. Even in the 1920s and 1930s, the division of the races was viewed as a stain on baseball, and it wasn’t uncommon for white and Black ballplayers to play against each other on “barnstorming” tours. Josh Gibson was known as the “Black Babe Ruth” and is accepted, today, as one of the greatest to ever play, despite never appearing in the Majors. But the top pitching star of the Negro Leagues, Satchel Paige, did make it after Jackie Robinson broke the color line in 1947. Paige, then in his forties, was a key cog on the 1948 Cleveland Indians team that won the World Series, the last Cleveland baseball team to ever win it all. Paige would appear in a game at 58, in 1965, tossing three scoreless innings while surrendering a double to Carl Yastrzemski, the Red Sox great.

Robinson, the Brooklyn Dodger infielder, became the first Black Major Leaguer in 1947, when my father was alive. Integration came late, and some teams accepted Black players more than others. The two New York National League teams, the Dodgers and Giants, eagerly signed Black stars, including Willie Mays, Monte Irvin, Don Newcombe, and Roy Campanella. Larry Doby, a great player in his own right, joined Cleveland just months after Robinson, enduring the same sort of vile racism. The Yankees and Red Sox integrated far later, thanks in part to racism on the part of ownership. In terms of Robinson, it’s important to remember what a fabulous hitter and baserunner he really was; in his prime, he was a second baseman who walked a great deal, hit for power, and stole bases. Had he not made history, he would’ve still been a Hall of Famer.

The story of baseball, in a conventional East Coast telling, comes to a tragic turn in the late 1950s. Both the Dodgers and the Giants left New York and moved to California, the Dodgers choosing Los Angeles while the Giants headed to San Francisco. For more than a half century, Major League Baseball had never gone west of St. Louis. The West Coast had the Pacific Coast League, which functioned, a bit like the Negro Leagues, as a repository of elite talent that didn’t make it to one of the 16 Big League clubs. The PCL was not a competitor to MLB, but it was something like a counter-league; certain clubs, like the San Francisco Seals, enjoyed larger followings than Major League teams (the hapless St. Louis Browns come to mind) and there were players who chose to stay on the West Coast and play there. The best, like DiMaggio, came east, and teams like the Yankees who scouted PCL stars developed large followings in California.

Inevitably, California would have Major League teams. Baseball, to succeed, had to go west, and it was only logical that established franchises like the Dodgers and Giants should plant their flags there. San Francisco and Los Angeles fans expected nothing less. The Yankees, the most dominant team of the 1940s and 1950s, could not leave New York. The Giants, once the royalty of the city, drew relatively few fans, despite their own success in the period, competing for National League pennants and winning it all in 1954. Losing money as the decade wore on, the Giants were eager to go. The Dodgers, so central to a borough that had once been, in the living memory of many, its own city, were another matter. In the new automobile age, Ebbets Field’s lack of parking was regarded as a severe handicap. What would have made it, a half century later, an ideal ballpark—easy subway and bus access, a central location in a populous county—doomed it in the eyes of Walter O’Malley, their owner, and many others who wanted to attract fans from the growing suburbs. The ballpark itself was cramped, aging, and needed to be replaced. O’Malley, villainized by New Yorkers for the rest of his life (Bernie Sanders included), actually wanted to keep the Dodgers in Brooklyn, hoping to get financing and permission to build a domed stadium in downtown Brooklyn, where the Barclays Center sits today. Robert Moses, the Master Builder, refused, demanding the Dodgers go to Flushing Meadows, which he aimed to make a crown jewel on par with Central Park. Moses dreamed of a baseball stadium anchoring the 1964 World’s Fair. O’Malley did not want to go to Queens. Los Angeles, naturally, became more alluring, and the rest is history.

It must have galled Brooklyn fans to see the new Los Angeles Dodgers win so quickly once they had been ripped out of the borough. In Brooklyn, the Dodgers had only won a single World Series, in 1955, and they were champions in Los Angeles in 1959. They would win again in 1963 and 1965. Koufax, their great Jewish ace from Bensonhurst, fronted the team, along with Don Drysdale, a Californian who pitched his first full season in Brooklyn’s very last. Baseball was stronger with a California juggernaut. The San Francisco Giants could never win a World Series in those years, but with Mays, Orlando Cepeda, Willie McCovey, and Juan Marichal, they were a force in the National League, battling mightily with the Dodgers. What would have broken me, had I been alive—I would’ve rooted for any Brooklyn baseball team if the option existed—was a blessing for the sport itself.

Baseball is cyclical. A power age displaced the stolen base. In the 1960s, in Los Angeles, the stolen base was reborn, when Maury Wills stole an astounding 104 bases in 1962. (In the prior decade, 20 or 30 was considered a high number.) The late 1960s would bring a definitive end to the Yankee dynasty and a return to the pitching dominance that last flourished in the deadball era. The strike zone had been widened and the pitcher’s mound raised, allowing for more downward momentum. Koufax, Bob Gibson, Tom Seaver, Denny McClain, and other hurlers lorded over the era, and 300-inning seasons grew again in number. Offense declined drastically. The designated hitter was introduced in 1973 to counteract the sliding number of hits and homeruns. In the American League, pitchers no longer hit. In the tradition-bound National League, they would do so until 2022. In the 1970s, baseball embraced the shagginess, idiosyncrasy, and tumult of the times. Uniforms were bright red, bright green, and the White Sox experimented with playing in shorts. Players wore elaborate moustaches and enormous afros. A pot-bellied pitcher tossed 376 innings, and didn’t ruin immediately his arm—he threw at least 300 innings for another three seasons. A ten cent beer night in Cleveland devolved, predictably, into a drunken riot. Disco Demolition Night was even more disastrous, ending with records blown up and fans storming the field.

Since the 1980s, baseball has not often captured the popular consciousness, losing out to the NFL and, at times, the NBA, but it remains a rich sport with a rabid regional following. It might have been 1998, at the height of the homerun chase between Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa, when baseball last captivated the entire country. The steroid era, encompassing my own youth, is now regarded as something of a dark age because of all the cheating; I would argue, having followed baseball through those decades, it was a very fun time to be a fan, regardless. Offense surged. Homeruns ballooned, but so did batting averages, and games were rarely a bore. The high-octane 1990s and early 2000s still managed to produce some of the greatest pitchers in baseball history—Pedro Martinez, Randy Johnson, Greg Maddux, and Roger Clemens—while cementing a bevy of position player icons, including Ken Griffey Jr., Derek Jeter, David Ortiz, Ichiro, and two of the most notorious all-time greats, Alex Rodriguez and Barry Bonds. Baseball felt enlarged. Bud Selig, who willfully ignored steroids, had the foresight to introduce the wild card, adding a round to the playoffs and giving the sport another layer of October drama. His second stroke of genius, the World Baseball Classic, would finally prove itself to the casual fan in 2023, when Shohei Ohtani, the two-way wonder, struck out Mike Trout, the best player of the 2010s and already one of the greatest to ever to play the sport, to win it all for Japan. Both happen to be teammates on the Los Angeles Angels of Anaheim.

A word on analytics, of which I have complex feelings. When I was a teenager, in the 2000s, the flawed conventional wisdom of baseball, like runaway patriotism after 9/11, was dominant. Pitcher wins determined Cy Young Awards, RBIs were sainted, and a player who walked a great deal could be said to be “clogging the bases.” On-base percentage was sneered at. If you watch (or read) Moneyball, you’ll understand, quickly, what I’m talking about. In my youth, I was aligned with the vanguard of sabermetrics, or using advanced statistics to gain a better understanding of the game. Sabermetrics helped fans know who was underappreciated and why certain strategies, like the sacrifice bunt, could be counterproductive. I was a regular reader of the sabermetrics-infused humor blog, Fire Joe Morgan, and did my best to understand what was emanating out of Baseball Prospectus. Though I was a Yankee fan, I could quietly cheer on the Billy Beane insurgencies out of Oakland.

In a sense, sabermetrics—or analytics, as it’s now known—was a victim of its own success. By the late 2010s, every baseball club had embraced a statistics-driven vision of the game. The sport quickly rubbed out its inefficiencies. In the 1980s, a player could steal 90 or 100 bases in a season, but mathematics taught you that each caught stealing could devastate a rally—therefore, better to try them much less, unless you were sure you could be safe almost every time. Bunts and hit and runs could give up outs (outs are, again mathematically, a team’s most precious resource) so better to scrap them altogether. Walks are efficient, and homeruns are even better. Strikeouts, once an embarrassment for people like me, could be embraced as long as enough walked were produced and homeruns were hit.

Pitching, too, came in for an analytics revolution. For almost a century, there was a built-in expectation that a starting pitcher, especially a great one, would try to pitch all nine innings. Over time, the number of innings a pitcher threw decreased—the 300-inning epics were gone by the 1980s—but it wasn’t as if, in the 1990s or even 2000s, the best pitchers weren’t throwing complete games from time to time. Pedro Martinez had 13 of them in 1997. Randy Johnson, at age 38, threw eight complete games in 2002. The late Roy Halladay managed at least eight complete games from 2008 through 2011.

The argument for limiting pitcher innings in the 2010s used to revolve around saving arms and avoiding injuries. But pitchers, as any fan knows, are still often hurt. The real rationale for curtailing complete games became strategic: why have a tiring Halladay or Martinez on the mound in the seventh inning when a fresh relief pitcher throwing one hundred miles per hour can be deployed instead? The rise of the bullpens, and the term bullpen game—to denote a game thrown entirely by relievers—characterizes the current era to a startling degree. Even the very best, like Gerrit Cole, cannot be expected to reach the eighth inning. Games inevitably hinge on bullpen use, with mostly anonymous, hard-throwing very young men vying with each other to snuff out offenses.

Mathematically, again, all of this makes sense. Batting averages have plummeted because elite relief pitchers are incredibly hard to hit. Today’s reliever is far more talented and intimidating than Goose Gossage or Rollie Fingers. Pitchers are trained to perfect their mechanics and “spin rates.” Since they only face a few batters, they can throw as hard as they can with maximum precision. The batter never has a chance. His only counter, really, is to try to hit a homerun. If he’s going to strike out three times in a game, he must make his moment of contact count. A single won’t do.

Finally, the late 2010s brought about the defensive revolution. Analytics, thankfully, allowed teams and fans to understand who the best defensive players really are without relying on eyesight alone or flawed statistical measures like the number of errors committed. The trouble came when every team embraced the defensive shift—stacking three infielders on one side of the field to swallow up base hits or abandoning third base, against the left-handed hitter, to create a four-man outfield. Right-handed hitters would come to endure shifts, though, as much as the lefties, and soon baseball entered its current stasis. The sport has never been richer in dynamic talent, but the style of play, unfortunately, has led to longer, slower games and fewer baseballs that are actually struck. The pitcher, quite simply, is too powerful, and teams don’t indulge in thrilling risks like the stolen base.

The pitcher’s power has replaced his mystique. I mentioned, before, the falling complete games, and how very few starting pitchers ever reach the eighth or nine innings. (Miami’s Sandy Alcantara may be the lone exception.) The glory of baseball, for much of the twentieth century, was watching the very best and most famous starting pitchers face one another in pivotal games. Seeing a pitcher go the distance—wondering how, with so little energy left, he was going to outfox the lineup for the fourth or fifth time in the afternoon—was one of the great joys of the sport. Again, I return to Koufax, who was perhaps the national sports celebrity of the 1960s, a man who made his reputation on coming back to pitch game seven of the World Series on just two days of rest—a pitcher typically enjoys four or five or even six rest days—and tossing all nine innings. Gibson, the legendary St. Louis Cardinal, finished most of his games too, as did Seaver of the Mets, Steve Carlton of the Phillies, and Fergie Jenkins of the Cubs. In the final inning of the game, with the very best on the mound, the tension of a big baseball game is unmatched.

The turning point of it all—when fans, at least, began to accept the new, more efficient future—was Matt Harvey’s performance in the fifth game of the World Series. Known as the Dark Knight, Harvey was, for several years, the best pitcher on the Mets and a candidate to succeed Derek Jeter as New York’s preeminent sports star. Harvey was a thick, swaggering presence, dating supermodels, partying late into the night, and boasting frequently of his own talent. I strangely miss him. In 2015, he helped lead the Mets to a rare World Series appearance, and took the mound with the season on the line. If he lost game five to the Kansas City Royals, it would all be over.

Harvey, who is my age, had a certain reverence for how the game used to be. When it mattered, he liked to keep pitching. And that night, at Citi Field in Queens, perhaps no one had ever been better in the history of the World Series. Through eight innings, Harvey had struck out nine and allowed no runs. As he left a mound, the crowd was delirious, chanting his name. The Mets manager, Terry Collins, told Harvey he wanted a reliever for the ninth inning. Harvey, his face glistening with sweat, barked back at Collins: he wasn’t leaving the game. He was going back to the mound. Collins demurred. Harvey would pitch the ninth inning.

Harvey walked the first batter. Then the baserunner stole second. The second batter doubled in the run. Harvey was done. Eventually, the Royals went on to win the World Series. The new baseball mandarins clicked their tongues: see, this is what happens when a pitcher tries to be a hero.

Harvey, soon beset by injuries, was never the same pitcher. Today, no team employs him.

Baseball’s declinist narrative is one it can’t quite shake, in part because the narrative itself, at this point, is about a century old. Sportswriters of the 1920s lamented that the Ruth-led power game had washed away the supposed ingenuity of deadball. Each generation of ballplayers inevitably believes their successors are somehow weaker or inadequate. There’s the old story of Cobb being asked, towards the end of his life, how well he’d think he’d hit in today’s game. “About .300,” the lifetime .366 hitter said, “but you’ve got to remember I’m 73 years old.” In Bang the Drum Slowly, my favorite sports film, a doctor treating the dying Bruce Pearson (played by Robert DeNiro) remarks that baseball is a “dying game.” The movie was released in 1973. It is true that for the first 60 years or so of the twentieth century, baseball was America’s most popular sport, rivaled only by boxing and horseracing. Of the three, baseball is the only one that hasn’t been banished to the fringe. More competition has crowded baseball out, but the sport was not terribly healthy in its supposed golden age. Attendance was often far lower than it is today, many franchises were cash-poor, and even the legendary Yankees played to half-full or quarter-full stadiums. Most teams began the year, in the pre-divisional era, with no chance of reaching the World Series. It’s true that the share of American-born Black players has declined over the last few decades but baseball, today, is a genuine global phenomenon. Few beyond the United States cared ardently about baseball in 1950 or 1960. All of the talent, with rare exceptions, was American-born.

If baseball can’t be the top priority of the American public any longer, it can be Japan’s number-one sport, the Dominican Republic’s number-one sport, Venezuela’s number-one sport, and Cuba’s number-one sport. It can be a national obsession for Mexico, South Korea, Colombia, and Taiwan. A World Baseball Classic game can be viewed by more than 60 percent of all Puerto Rican households or find higher ratings, in Japan, than the Tokyo Olympics. For several decades now, many of the top Major League ballplayers have come from beyond the United States. Ohtani, who hits and pitches like Ruth, is Japanese. Miguel Cabrera, the last Triple Crown winner, is Venezuelan. Yordan Alvarez, who conjures Gehrig, is Cuban. Counting the number of Dominican superstars now is almost impossible. At least one third of the sport is Latino and the Asian population will continue to boom as more of the top Japanese and South Korean players head to the United States.

Within the United States, the handwringing over baseball’s future is overblown. The NFL is preeminent, but so what? In America’s largest cities, you’d be hard-pressed to argue baseball isn’t the most popular sport or a close second. Consider the Yankees and Mets in New York, the Cubs in Chicago, the Dodgers in Los Angeles, or the Red Sox in Boston. They are now baseball-mad in San Diego and have always treated it as religion in St. Louis. Football will dominate the South, but it’s not as if the Houston Astros or Texas Rangers are starving for fans.

Baseball, like the NBA and NHL—the NFL, for now is immune to worry—will face a new threat in the number of people who no longer subscribe to cable television. Cord-cutting threatens a major revenue source for all three of these leagues. Gen Z is, generally, less interested in live team-sports, and immersive internet technologies continue to devour attention spans. As the youngest generations enter full adulthood, this is undoubtedly a concern.

The prestige media has paid attention to baseball this spring because it has undertaken its most radical rule changes since the DH was instituted a half century ago. The elaborate infield defensive shifts, which gobbled up so many singles, have been outlawed. Pitchers can only make two pick-off attempts at a baserunner. The bases have been slightly enlarged to encourage, like the pickoff rule, more base stealing. And finally, a clock has been introduced to compel pitchers to throw within a specific timeframe and hitters to stay in the batter’s box.

The changes are controversial; I support all of them. The 2010s was held captive by the very same analytics-driven visionaries whom I once cheered on. Strategically-sound baseball isn’t the baseball that is in the best of interest of the fan. It’s often the inefficiencies that are most entertaining. Like the NFL, baseball is realizing that it can tinker with its rules and procedures to make a game more watchable. The NFL lives in fear of football devolving into a defense-first slog; hence, all the changes to protect quarterbacks and open up the passing game. Baseball, with its ban on defensive shifts, larger bases, limitation on pickoff throws, and a pitch clock to force faster encounters between the hitter and pitcher, will do this too. Traditionalists need not worry. The irony of all these changes, as sweeping as they seem, is that they are restorative. They make baseball as it once was. Watch an old game from the 1960s or 1970s and see how a hitter rarely left the batter’s box and the pitcher got the ball and threw it right away. See how a player like Lou Brock or Vince Coleman or, of course, Rickey Henderson could steal 100 bases in a season. The new rules will incentivize the stolen base, the single, maybe the hit and run. Power won’t vanish—and I don’t want it to—but maybe, just maybe, we can see someone challenge Williams’ .406 mark in a shiftless game. How fun would that be? Imagine a player, on October 1st, teetering on that magical edge of .399. One game remains. He needs at least two hits, and the first comes easily, a sharp single past the second baseman. The second chance, though, must wait until the ninth inning, the very last at bat of his season. The ball is slapped down the third base line, rolling gently fair, and the third baseman must take it bare handed. He’s one of the very best and he does it elegantly, in one fine motion, and the hitter is halfway to first, three quarters of the way, the ball now shooting across the diamond to the outstretched mitt of the first baseman. Here it is, foot crashing over the bag, ball in glove, a single cry from the mouth of the runner and the umpire, his arms outstretched, and he’s—

I got the baseball stats bug reading Bill James' first Historical Baseball Abstract in the late 1980's. Since then I've seen the "metrics" ruin much of the sport. Watching them ruin Strasburg's career by 'protecting' him has been awful.

Great essay. Extremely enjoyable.

I'm all for the new rules too. I always point people to this chart: https://www.baseball-reference.com/leagues/majors/misc.shtml

Games averaged 2 1/2 hours in the 1970s versus more than 3 hours in the past decade. The new rules seem radical but they're really a return to what baseball used to be.