How to Define Woke?

The debate rages on

If you’re a person who spends time online, you might have come across a recent round of debate and handwringing over how to define “woke.” The word itself is something of a hand grenade, and carries a variety of shifting meanings that depend on the context and the ideology of the user. The debate raged anew because Bethany Mandel, a conservative author, struggled to define “woke” and “wokeness” in an interview with Briahna Joy Gray, a leftist political commentator. Gray, an attorney and former Bernie Sanders press secretary, is very good at what she does, and she employed a rather underrated tactic for anyone conducting an interview: ask the subject straightforward, fact-based questions. Make them define a term or explain a policy. Mandel plainly failed.

So what is it, anyway? There is a way to describe woke before the 2010s and the more contested definition we’ve come to know today. Woke was a shorthand for “stay woke,” a phrase employed in various activist circles in earlier decades. It held particular appeal in the Black community. Jumaane Williams, the New York City public advocate, was known for wearing a “stay woke” button long before the term became fodder for the culture wars. “All woke really means — and it’s ever meant to me — was people who were aware of injustices that occur, aware of discrimination, aware of systems that exist that are exploitative by nature, that are based on privilege,” Williams recently told Politico. And he isn’t wrong—telling someone to “stay woke” merely meant ensuring they were alert to the grim realities of racism, discrimination, and exploitation in the United States. If a person was “woke,” they knew their history. They understood slavery, Reconstruction, Jim Crow, and the Civil Rights Movement. They didn’t live in ignorance.

Woke has since evolved. The best primer for all of this, as usual, comes from Freddie DeBoer, who extensively defined “woke” in the 2010s and 2020s context in a recent piece on his Substack. I encourage you to read it. I don’t have a great amount to add and I agree with all of it. DeBoer prefers the phrase “social justice politics” and expresses his frustration with left-leaning activists and commentators who refuse to name their relatively new movement. In the absence of their ability to define fresh obsessions with DEI and white fragility, others have moved in to reappropriate woke.

Rather than merely copy and paste DeBoer, I am going to do my best to boil down what I think the newest itineration of woke really means. It’s informed, partly, by my own left perspective, and I’ve found it’s a rather simple way to think about it if, like Mandel, you’re forced to come up with a definition on the spot.

Woke is identity politics absent class politics.

After several years of observation and writing on the topic, this is the best way I can distill all of it—the various clashes over culture, representation, and language that simmer into this decade. Some of those who foreground identity over class concerns may rail, from time to time, about the failures of capitalism, but they do not proffer a socialist regime as the answer to the ills of American society. They do not observe inequality and declare that America needs a far more generous social safety net and universal, free healthcare. They do not seek to strengthen tenant laws or talk about the need to develop far more subsidized housing. They do not say much about labor unions or workplace rights.

The foundational moment for modern woke, if there is one, is probably Hillary Clinton’s declaration during the 2016 election that “if we broke up the big banks tomorrow — and I will if they deserve it, if they pose a systemic risk, I will — would that end racism?” Clinton was criticizing Sanders, a democratic socialist who promised, as president, he would try to rein in the banking sector. Her implication, as a proud capitalist, was that one had to address racial injustice as a separate issue entirely, and that any attempt at redistribution or a bolstering of the safety net could be viewed skeptically because it would not obliterate racism. Indeed, Britain’s National Health Service or Canada’s single-payer system has not solved racism in those countries. But it has allowed working-class, marginalized people to receive the kind of healthcare that is wildly overpriced in the United States.

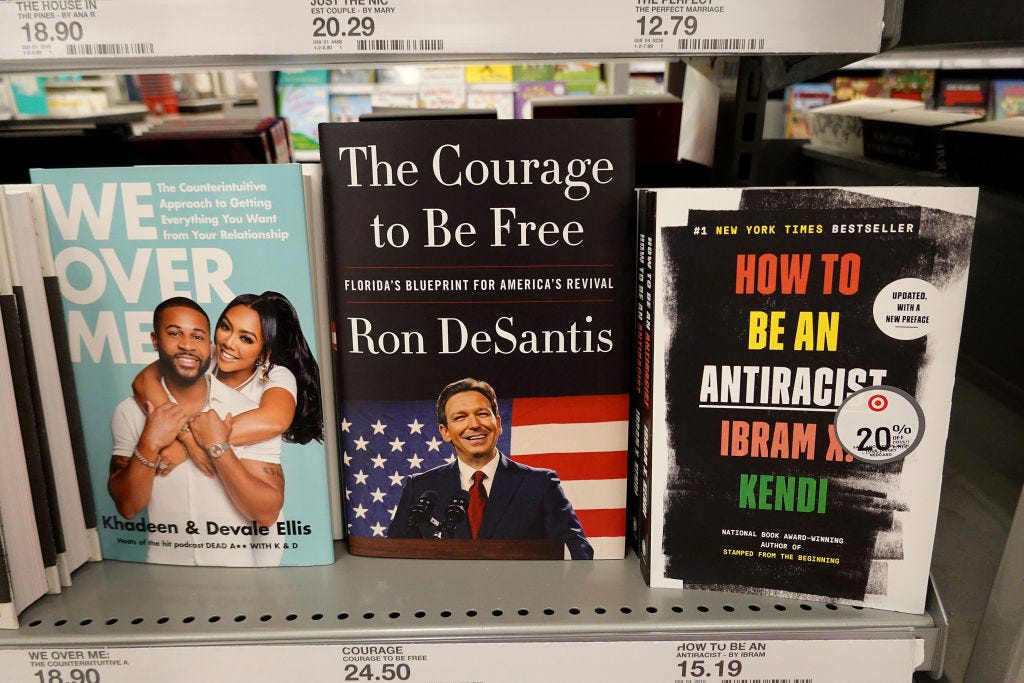

Proponents of woke—again, they wouldn’t call themselves this—speak frequently of systemic and structural oppression in the United States but offer solutions that either place emphasis on the individual to overcome these structures or devise identity and language-based approaches that remove the need for agitation on questions of economics. Robin DiAngelo of White Fragility fame and Ibram X. Kendi, who considers class more than DiAngelo does, became the most well-known and well-compensated faces of this new politics. Kendi popularized the idea that metrics that exposed racial inequality, like standardized tests, were themselves racist. DiAngelo argued, inherently, that racism could be solved if enough white people were subjected to anti-racism training and DEI seminars that soon became widespread at white collar corporations and academia. In DiAngelo’s formulation, class does not matter much at all. A white single mother who works at a Walmart in Indiana is not so different than a tenured white professor at Columbia University. A Black corporate executive, similarly, cannot be cleaved from a Black public housing resident in Queens.

Racial identity, for those fully invested in the woke approach, either takes dramatic precedent over class or excises it entirely. A fully woke world will not do much to improve the material conditions of Black, Latino, and Asian Americans, but it would elevate the brightest or luckiest of them into more privileged positions in academia, the media, and Hollywood. Representation is relevant, and we must move as far away as we can from the overt racism that characterized the twentieth century. What DEI cannot do, though, is fix housing or fund more afterschool programs in a Black neighborhood. Harvard’s diversification will not save a diabetes patient on the East Side of Buffalo from medical price-gouging. A generation of enlightened professional class readers of White Fragility are not going to force Amazon to pay their warehouse workers, many of them nonwhite, more money. DEI, certainly, is not going to convince any Amazon executives to stop breaking unions.

In some sense, this all may begin to matter less. The attention and energy around DiAngelo and Kendi peaked in 2020. Most people laughed when Elon Musk began frothing about the “woke mind virus.” Ron DeSantis will soon have to start talking about Medicare and Social Security; Donald Trump, of all people, is going to force him to do it. Culture wars evolve. Definitions change. The debates of the 2030s and 2040s may be unrecognizable to us today. So it goes.

Without turning your comments section into a theory seminar, can we really talk about the elision of class politics in American left activist circles without acknowledging the dominance of postmodern (largely French) theory in American academia by, at latest, the late 20th century? Most of these guys reacted to May '68 and affluent post-war society by bitterly distancing themselves from the metanarrative of global class struggle and communism. They paid a high psychological wage for doing so, and it's reflected in the cynicism of their theories. American grad students (most without a previous grounding in lived class politics) encountered critical theory first, and class analysis second (if at all). Academics and cultural critics who pointed out the cravenness of all this were generally dismissed as some variant of -ist. I'm beginning to think that the critique that this is "overstating the influence" of obscure academic theories is related to the very evasiveness DeBoer criticizes in this left tendency rejecting all proffered labels for itself. There may be no such thing as the slippery slope fallacy in an affluent and highly technocratic society with an overproduction of elites.

'Woke' is, as mentioned in the article, is a phenomenon of the primarily Elite Academic schools, and the Corporate Boardrooms.

There is, thankfully, little to no version of the modern 'woke' cloddishness in the Bad Neighborhood. We've had 3 black teenagers killed in the last 3 years - all by other teens. The latest was last week.

We have tons of violent fights. No wypipo involved. To think that some white female with blue hair (or anyone for that matter) is going to come in and scream about 'whiteness' or 'systemic racism' is ridiculous. The College educated woke lecturer also stays away as the number of white republicans in charge is zero. The Grift Potential is in the negative.

We have bigger, much more serious fish to fry. No Kendi, no DiAngelo, no woke babble infiltrates the school district border. These people are never mentioned at staff development sessions or meetings.

It's nice because we have to work on real solutions, not words that might offend some coddled Ivy grad who thinks that history began in 2020.