Is New York Going to Elect a Republican Governor?

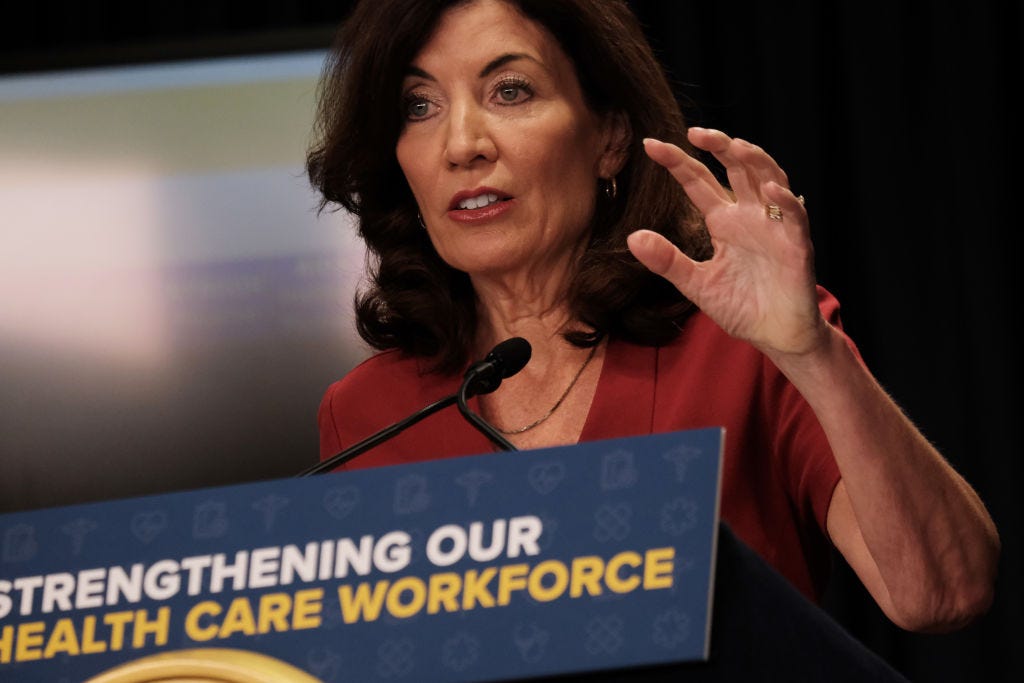

The muddle of Kathy Hochul

When I wrote on the New York gubernatorial race for Crain’s, I tried to speak to Kathy Hochul, the incumbent governor. The campaign politely never made it happen. I was not really surprised. She hadn’t granted many interviews or done all that many public campaign events. There was a political argument, at least, that she shouldn’t bother with me or anyone else, particularly when I was bound to ask a few pesky questions, like how she planned to fix and fund the MTA if she won a full term in November.

Hochul was in cruise control for much of the summer and fall, following much of the same playbook Andrew Cuomo wielded for three comfortable general elections victories in New York. She raised enormous amounts of money from every special interest imaginable, consolidated the backing of organized labor, and crushed her insignificant challenge on the left. The downfall of Roe v. Wade was another political gift, with Hochul able to hammer away at her Republican rival, Lee Zeldin, an unabashed Trump backer who promised he’d appoint a “pro-life” health commissioner. Cuomo, the disgraced former governor, won his last general election by 24 points in 2018, a blue wave year, and if Hochul wasn’t going to match that margin, there was every reason to believe she’d be running up the score against Zeldin.

Oh, how the polls have tightened.

One, from the reputable Quinnipiac, showed Hochul leading Zeldin by just 4 points. Another had Zeldin technically ahead. On average, her lead is down to just 6 points, even if certain pollsters like Siena College still show a double-digit margin. The trend is clear: Zeldin is getting closer, as close as any Republican has come since George Pataki won his final term 20 years ago.

But can Zeldin do it? Can a Long Island congressman who refused to certify the results of the 2020 election win a state that hasn’t voted for a Republican presidential candidate since 1984?

Probably not. He can get close enough, however. And Hochul, with her forgettable dreadnaught campaign, needs to be aggressively making her case in the days leading up to November 8th, when Democrats are probably going to lose many House and State Senate seats in New York. It’s getting ugly out there fast.

Zeldin’s success isn’t much of a mystery. He is not a particularly charismatic or compelling candidate; he was a garden variety right-wing congressman and former state senator who threw himself into the Trump movement and never left. Unlike Charlie Baker and Larry Hogan, he’s made few concessions to the Democratic lean of his state. If Zeldin managed to win, he’d probably try his best to ape Ron DeSantis, leaning into the culture war and governing for the bright lights of Fox. He’d want to run for president.

Zeldin has, undeniably, tapped into the mood of the electorate, as have many Republicans running in a midterm year bound, as always, to punish the party in power. Covid created some nasty domestic and global problems that are, along with the war in Ukraine, contributing to stubbornly high inflation. Crime is not high by historical standards but it is higher than it used to be, and many voters are enraged about violent attacks on the subway and various petty thefts. There’s an unease in the air, an ill wind, somewhat like the one that blew through 50 years ago this fall, and Democrats will face the consequences. In New York, Republicans, with help from local broadcast media and the tabloids, have effectively tied much of the crime spike to bail reform laws passed in 2019, even if crime increases are happening in many states where no changes were made to the criminal justice system in the last three years. What is clear, though, is that Democrats lack an effective counter-narrative: the famed pollster Stan Greenberg has gone as far to say that even talking up the legislative accomplishments of Joe Biden and the Democratic Congress is a political loser.

In New York, Hochul has found little to tout of her own record, her argument in TV ads reduced to Zeldin being too much of a Trump acolyte to run the state and her ongoing fight to defend abortion rights, a political winner over the summer that seems to matter less now, with crime and the economy taking center stage. While there are many factors beyond Hochul’s control—most local politicians, these days, are buffeted by the forces of polarization and nationalized political concerns—she’s done very little to convince voters she herself deserves another term. What is Hochul for, really? From the campaign, it’s not terribly apparent. When I asked her team what she wanted to do with the next four years as governor, she had no tangible answer.

Public events and staged rallies may be a bit overrated by the press, but showing up can matter, especially when regular people feel so alienated from their government. Hochul has kept a relatively light campaign schedule in the fall. She has not been in New York City nearly enough, where Zeldin has been spending increasing amounts of time. A few Democratic politicians, like the Manhattan Borough President Mark Levine, have tried to sound the alarm over Zeldin’s momentum for weeks now. The Democratic electorate is complacent enough but Hochul’s $40 million hasn’t yet bought a way out of this complacency; there is, unless things change, going to be a turnout problem for the Democratic ticket. Republicans are more angry and more excited.

Andrew Cuomo was not a terribly talented politician, but he was a brute operator with deep roots in New York City, where a lot of the votes are. His father was governor for 12 years. He had little trouble whipping labor unions and interest groups to do their part for him come election time. He had a connection with older Black voters in Brooklyn and Queens who still fondly remembered Mario Cuomo. Three times, somehow, he carried Staten Island against Republican opposition. Hochul, from the Buffalo area, lacks all of these downstate ties and she hasn’t done nearly enough to make up for the time she missed in Hollis and Rosedale and Bushwick. Weekend church visits aren’t enough.

If she’s not mobilizing the moderate, outer borough working-class voters who also came home to Cuomo, she’s not appealing to the rising professional left either. In New York City, the Garcia-Wiley vote of 2021—a coalition extending from Manhattan to the brownstone belt to places like Fort Greene and Astoria—proved itself potent, a force in Democratic primaries that will be needed to ensure a comfortable general election margin. Hochul should be on the phone with socialists like Julia Salazar and Jabari Brisport. She needn’t campaign with them directly, but she needs their help and their networks. They’re going to have to sell their supporters on Hochul as a person worth voting for at all.

In one sense, Hochul is lucky. Zeldin as a proud conservative will probably hit a ceiling in New York, especially as the news spreads to regular Democrats that the election is close and a Trumper could be governor. A different kind of Republican could have defeated Hochul outright. Harry Wilson, the wealthy businessman and former Obama administration official, couldn’t find his way out of the gubernatorial primary in June, too much of a moderate to compete with Zeldin and Andrew Giuliani. Wilson was nearly elected state comptroller in 2010, another red wave year, and could have easily sold himself to the general electorate as a tough-on-crime, socially liberal Republican in the mold of Michael Bloomberg. Wilson, especially if he was supportive of abortion rights, would’ve vexed Hochul. Zeldin, politically disciplined but ideologically rigid, needs to hunt up a lot more votes from dissident Democrats and left-leaning independents. Can it be done? Hochul, for her own sake, better campaign like it can happen.

If Zeldin does win, there’s a good chance Democrats not only lose their supermajority in the State Senate but their full majority altogether. If that scenario isn’t chilling enough for the left, imagine another: a rested and revitalized Andrew Cuomo, with millions still to spend, announcing an early gubernatorial bid for 2026. He can fight his way through the primary. And then Governor Zeldin is his.

You get the sense she thinks having to campaign is beneath her. Hubris is never a good look, but it looks especially bad on someone with so little to be hubristic about. What a disaster.

Hochul is why identity politics is such a disaster. Female politicians are generally less popular because of cultural misogyny; when you’re a do nothing moderate like her, there’s no constituency.