Jann Wenner and the Problem with Poptimism

The music discourse boils over

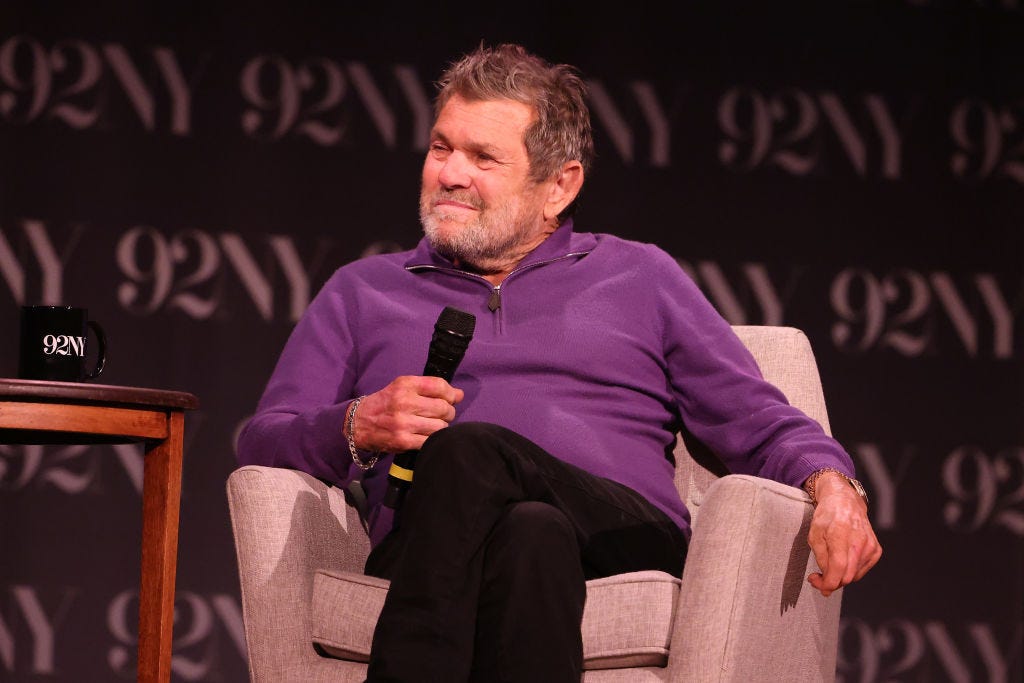

Jann Wenner, the bilious Rolling Stone founder, is sure he knows genius when he sees it. His new book is a collection of interviews he conducted with seven gods of rock, all of them white and male. To promote this book, Wenner gave a lengthy interview to David Marchese of the New York Times. Unfortunately for Wenner, who admitted to Marchese that he often allowed subjects like John Lennon and Bono to edit their own interviews to gut unflattering material, Marchese granted no such privilege. Wenner was on the record in all his racist and misogynistic glory. Black and female artists were not Wenner’s “zeitgeist” despite Rolling Stone’s formative years overlapping with an explosion of Black and female musical talent in the United States, from Marvin Gaye to Joni Mitchell to Carole King to Jimi Hendrix to Sly and the Family Stone. “Insofar as the women, just none of them were as articulate enough on this intellectual level,” Wenner declared. “It’s not that they’re not creative geniuses. It’s not that they’re inarticulate, although, go have a deep conversation with Grace Slick or Janis Joplin. Please, be my guest. You know, Joni was not a philosopher of rock ’n’ roll. She didn’t, in my mind, meet that test.”

“Of Black artists — you know, Stevie Wonder, genius, right? I suppose when you use a word as broad as “masters,” the fault is using that word. Maybe Marvin Gaye, or Curtis Mayfield? I mean, they just didn’t articulate at that level,” Wenner continued. “I mean, look at what Pete Townshend was writing about, or Jagger, or any of them. They were deep things about a particular generation, a particular spirit and a particular attitude about rock ’n’ roll. Not that the others weren’t, but these were the ones that could really articulate it.”

Wenner’s quotes, equally offensive and nonsensical, were enough to have him removed from the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame Foundation’s board. My own view of protected speech is rather liberal—I am very proud this nation has a First Amendment—but there’s no entitlement to sit on the board for a music hall of fame when your understanding of popular music is so impoverished. As a Baby Boomer extraordinaire and a one-time enfant terrible who lent a significant boost to Hunter S. Thompson’s journalism career, Wenner is a perfect avatar of his era’s self-satisfaction: we made everything, everything was better then, and nothing can convince us otherwise. And for those who resented rock ‘n’ roll’s supremacy in the twentieth century culture, Wenner’s vitriol was further evidence that the so-called poptimists were on the right side of history and the rockists needed to fade away. “Poptimism was a corrective to a critical consensus that hallowed white dudes w/guitars above all others,” the author Jody Rosen wrote in a post that was liked more than two thousand times.

Indeed, monocultures are stifling, and no one wants to live in a world where only one type of person and one type of music dominates the charts and all the critical chatter. If Wenner himself had been as hegemonic as imagined—if every other rock critic of the era, particularly the white men—this “corrective” would have been an unalloyed good. But there were men Wenner’s age and older, like Robert Christgau and Greil Marcus, who were long celebrating the music of Black and female performers. Wenner’s 2023 views would have been retrograde by the 1970s, when even that era’s racism and sexism couldn’t dim public and critical enthusiasm for music produced by women and people of color. No one was stopping Fleetwood Mac or Michael Jackson. By the 1990s, Wenner was the editor who was firing a rock critic for handing down a negative review of Hootie & the Blowfish. I can’t think of a more banal form of poptimism than that—punishing a critic for daring to censure a band that was, at the time, enjoying great commercial success.

What is strange about today’s moment is how the winners can’t stop pretending they haven’t won already. Rock, in almost all of its permutations, has been driven out of the top 40 unless you count country music, a genre that is rock but is also distinct from it, and no longer includes, for the most part, the sort of existential, ambiguous ballads that made Johnny Cash or “Wichita Lineman” era Glen Campbell famous. In rock’s heyday—whether it was the arena anthems, punk, the pop and psychedelia of the Beatles, the chamber pop of the Beach Boys, Nirvana’s grunge, the explosion of blues rock and jam bands—there were many other kinds of music that also filled out a top 40. Soul, disco, R&B, hip hop, new wave, funk, and dance-pop all thrived alongside rock. Wenner’s myopia is more the exception than the rule—there were plenty of music journalists at both mainstream newspapers and in the alternative press who wrote generously about these genres of music and upheld the idols of that period.

At the same juncture, dissent was tolerated. Poptimists—those who regard contemporary pop music, and little else, as high art—and writers like Rosen who celebrate their dominance fail, repeatedly, to acknowledge we now function in a milieu where critical takedowns of popular artists are not allowed to meaningfully exist and countercultures themselves have withered away. There is rarely such a thing as a publication commissioning a piece that argues Taylor Swift’s Midnights is not one of the great albums of the year (if not the last 10) or examines, more broadly, whether Swift has innovated pop music in any significant manner. I am not here to proclaim anything about Swift. It must be said merely that the industry of music critics, hollowed out by the broad decline of print media, cannot produce anything but hosannas from their weakened position. Richard Goldstein might have been wrong about Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, but hordes of Beatles fans and rock journalists weren’t going to damage his career for his contrarian view. It was understood that even the most acclaimed musicians could endure criticism. Rock critics gleefully eviscerated Paul McCartney’s first solo albums. The world kept turning.

Not very long ago, there was an entire alternative ecosystem that worked in harmonious tension with the mainstream. Whether you were into indie rock, obscure hip-hop, or anti-capitalist punk, there was a world of print magazines, small newspapers, and even blogs to inculcate a counterculture. As recently as the 2000s, it was possible to gain momentum as a rock band by achieving acclaim on various small blogs—often, they would compete with each other to find the best “new” band—before finally gaining recognition from Pitchfork. Pitchfork’s power, relative to its independent sphere, was far greater than any Rolling Stone ever enjoyed since they could, almost single-handedly, make or break a small band’s career. (As my friend reminded me, Wenner’s fulminations against Led Zeppelin couldn’t stop them from selling out arenas.) Pitchfork’s review style could be snide and needlessly cruel, and we should not root for a culture where one website is the arbiter of taste. But Pitchfork, defanged in the 2020s, is now another interchangeable poptimist organ, meekly handing out high grades to enormously popular acts so the social media backlash will never come for them.

To the modern mind, the 1990s aversion to “selling out” can feel as absurd as declaring you won’t ride in any vehicle that isn’t pulled by a horse. The Gen X trope earned some of its mockery, but not all of it—there is a balance to be struck between reviling anyone who wants to make a comfortable living from their art and wildly celebrating those who chase the most ludicrously commercial outcomes imaginable. TikTok culture is decidedly worse than the culture that fulminated against “selling out,” I am sorry to report. Monetizing life itself—incubating an entire new class of “creators” and “influencers” who manufacture near-infinite amounts of mostly derivative videos that last under a single minute—is not, on its own, a virtue. If you can become a millionaire doing it, more power to you. At least there was a time when a healthy debate could break out over commercial imperatives. Some singers and bands could hunger for great fame and riches, making the music that would get them there. Much of the best music ever produced was also widely popular. My favorite band of all, the Beach Boys, were tremendous sell-outs. Punk rockers loathed them. Pearl Jam, in the 1990s, achieved commensurate fame and spent much of that time shunning interviews and suing Ticketmaster. They would occupy the world stage on their own terms. Most of the sell-outs of the twentieth century, meanwhile, expected only riches; critical appraisal would have been the bonus, a happy discovery. Their fans would feel the same way. An indie director who decided to make a film about the most iconic intellectual property in the world would not get dispensation from the critics while reaping her millions. Back then, the poptimists were merely one part of the horde, not all of it. Their triumph was not yet total.

One of the things that makes me laugh amidst all the huhbub here: When has Mick Jagger ever been thought of as an intellectual?

"What is strange about today’s moment is how the winners can’t stop pretending they haven’t won already."

It's only superficially strange. Wokery can never admit that it has won, because being "oppressed" is the ultimate sign of virtue.