Michael Bloomberg Raised Taxes to Save New York From Economic Catastrophe

Andrew Cuomo still won't do it. We will be in trouble if he doesn't.

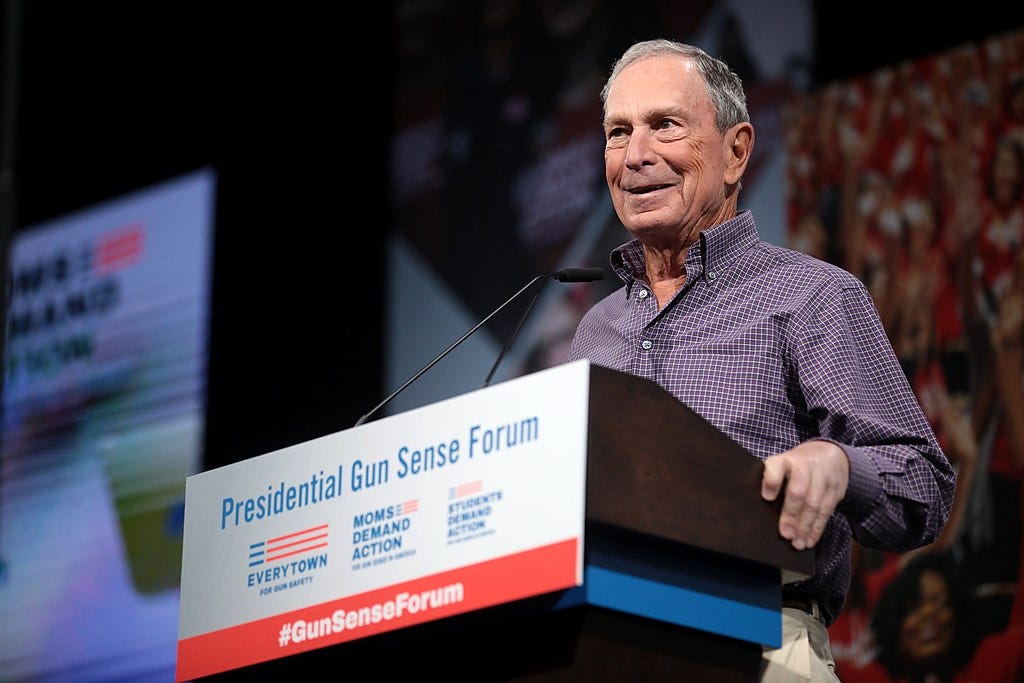

Those who aren’t new to my writing know I’ve been an unsparing critic of Michael R. Bloomberg, New York City’s 108th mayor. When Bloomberg ran for president, I branded him an oligarch—an accurate label the campaign chafed at—and openly wondered about what damage such a wealthy man would do to democracy if his campaign were successful. I wrote about his problematic record at City Hall, including his bloodlust for stop-and-frisk and his authoritarian crackdown on protesters at the 2004 Republican National Convention. Bloomberg, a believer in science and a longtime supporter of socially liberal causes, would have been a preferable alternative to Trump, but there was no need for voters and party activists to throw in their lot with a former Republican who backed the Iraq War when there were better candidates to face Trump.

It should be understood that I don’t view Bloomberg’s 12 years as mayor in an entirely disastrous light. There were moments of courage and foresight, like banning smoking indoors, speaking early about climate change, advocating for gun control, and embracing same-sex marriage before it was fashionable. He created the 311 system for registering complaints and attempted to make the city more pedestrian-friendly. None of these achievements, in my view, can override his greater sins, but they are a part of the record. Another was his unpopular move, at New York City’s lowest point before now, to dramatically raise property taxes in the five boroughs. Bloomberg’s recognition that a tax hike would be needed to stave off further budget cuts in the wake of the September 11th attacks stands in contrast to Governor Andrew Cuomo’s current position, that the millionaires and billionaires of New York must be protected at all costs, even with schools, transportation networks, and hospitals in peril. Cuomo believes the federal government should bail out New York, which in a just world would happen. But that government is Donald Trump and Mitch McConnell. Living in a real world, in which Republicans are deeply hostile to New York City and no new aid package is forthcoming, Cuomo must understand that tax hikes, as well as borrowing, must be considered to avoid what would be crippling, long-lasting austerity.

Bloomberg ran as a Republican in 2001, triumphing in the shadow of 9/11. He narrowly defeated a Democrat, Mark Green, who had been, at one point, heavily favored. Bloomberg won by both vastly outspending the liberal Democrat and convincing voters he was the technocratic manager needed to guide New York out of a crisis. In early 2002, Bloomberg vowed, as a fiscal conservative, not to raise taxes. But the economic environment then, like now, was devastating. Locally and nationally, 9/11 had induced a recession, depressing travel and sapping New York’s tourism industry. Both 9/11 and the COVID-19 pandemic were crises that eviscerated New York with little prior warning; neither were imagined in any financial planning, and each delivered once-in-a-generation shocks to the city’s system. (I couch the previous sentence with “little” because it was clear, by February, coronavirus would make it to America and infect people.) COVID-19, tragically, may do more long-term harm than 9/11. Far more New Yorkers were killed and the business shutdowns were more widespread. In each case, the specter of the 1970s—when a fiscal crisis drove New York City to the brink of bankruptcy—was invoked, with deep cuts threatened to essential city services.

Bloomberg, to his credit, eventually understood he could not simply slash the city’s budget and hope for the economic crisis to pass. Tax hikes, as well as borrowing money, would be needed. New York City needs the state government’s permission to raise income taxes—Bloomberg wasn’t a fan of the idea, and the Republican governor at the time, George Pataki, certainly wasn’t going to let him do it in his election year—but it doesn’t need the same authority to hike property taxes. Under Bloomberg’s predecessor, Republican Rudy Giuliani, property taxes had remained flat. Raising them in any way had long been considered a third rail of municipal politics, with vote-rich, home-owning neighborhoods waiting to rebel against anyone who increased their tax bills. While many people who pay property taxes in New York City aren’t wealthy, property-owners still enjoy the great privilege of equity over the millions who rent and live, in many cases, paycheck to paycheck.

Bloomberg decided, in late 2002, to raise property taxes, enraging the city’s real estate lobby, which the billionaire otherwise enjoyed a very close relationship to, especially as he pursued an agenda centered around luxury development. He had already borrowed more than a billion dollars to balance his first budget as mayor. After floating hikes as high as 25 percent, Bloomberg and the City Council settled on an 18.5 percent increase. Ambitious and admirable, the hike would put the city on sound fiscal footing while proving Bloomberg, a first-term Republican mayor in a Democratic city, was willing to practice lousy politics to reverse New York’s dismal economic condition and stave off even harsher budget cuts. Under Bloomberg’s plan, people in an average single-family home saw their tax bills rise to $2,024 from $1,853; people in an average co-op saw their bills go to $2,931 from $2,683; and people in condominiums saw an average rise to $4,939 from $4,521. If the increases could be onerous, they at least hit those who owned property and could, for the most part, absorb them. The decision appeared to endanger Bloomberg’s own re-election bid. A year later, his popularity had plummeted: only 32 percent of New Yorkers approved of his performance. "As taxes go up, Mayor Bloomberg's job approval goes down, down, down," said the late Maurice Carroll, who directed the Quinnipiac University Polling Institute.

Instead of depressing New York’s economy further—all conservatives warn of virtually the same thing when tax hikes are proposed—the property tax increases helped fill the city’s coffers as the fiscal situation gradually improved in subsequent years. The bold move would pay off. City spending grew again and a reserve fund was created. Bloomberg weathered criticism of the large property tax increase to survive re-election in 2005, helped along by a personal campaign expenditure of nearly $78 million, an absurd number that his Democratic opponent, Fernando Ferrer, could not overcome. Bloomberg, like Cuomo, would repeat the canard that raising income taxes on the wealthy would force them all to flee, but he at least took one risk, during a nadir in the city’s history, to raise revenue and help save the economy.

The lesson for today is rather simple: absent federal aid, Cuomo cannot merely gut the state’s budget and hope, somehow, he presides over a recovery. That’s fantasy economics. Austerity is self-defeating. Even Bloomberg, one of the richest men in history, knew this. If New York City is forced to fire large percentages of its workforce and slash services, the economic downturn will only persist longer, as more people look for work, demand falls, and the population declines as many decide it’s not worth living in a city with extremely curtailed public transit options or limited garbage pick-up. Tax hikes alone cannot restore the state budge to full health; without a massive federal aid package, some cutting will have to happen. But the goal should be to avert as much of it as possible. It’s unclear Cuomo, who entered office as a tax-cutting Third Way Democrat, has any great desire to protect these public services. Bloomberg, for his many faults, did.

I mean, David Patterson did too. That didn’t stop him from trying to create a coalition opposed to raising taxes this time around (and falling flat on his face). Remember, the US didn’t dive directly into austerity from the start of the crisis like the EU did- it passed a stimulus package, lame as it was, back in 2009. I assume that mentality was resonant back then.

The neoliberal austerity framework has only gotten stronger here and abroad since then. You’d probably hear a different tune from Bloomberg right now if he had a say.