My 2021 in Reading

I set a new personal record

“Writing is so hard,” the legendary critic Elizabeth Hardwick once said. “It’s the only time in your life when you have to think.”

There are, of course, many opportunities presented for serious thought in everyday life, but it is in the act of writing—and, of course, reading—where I find my mind makes new and exciting demands of itself. I confront the blank page, ready to fill it with words. As a reader, I am in delicate dialogue, alone with this voice, finding my way—I hope, at least—to some form of enlightenment.

My approach to reading is two-pronged. I am there to enjoy myself, to pass time, to explore a world I would never have known otherwise. In the most rudimentary sense, I am there for a kind of enrichment, an almost ineffable quality that I hate to reduce to something merely ameliorative. Reading shouldn’t be like taking a vitamin. You shouldn’t read to make yourself a better person, though that might be an ancillary benefit.

I read, also, as a writer. I believe there is nothing more important for a writer than reading. When I teach college classes and students ask me how they can become better writers, my answer is always simple: read more. Read novels. Read the newspaper. Read magazines. Read nonfiction books. Read, read, read. See how the greats tinker with sentences and clauses, how rules are made and broken and recomposed anew. Read widely. As a novelist, a journalist, and a columnist, I can only be successful if I am living my life in words.

Before the age of eighteen, I did not know what I wanted to do with my life. For reasons still not entirely clear to me, I was seized with the notion, in the second semester of my freshman year in college, that I should be a writer. Perhaps it was reading Martin Eden, one of my mother’s favorite books. I wanted to write great novels, too. Knowing that books alone didn’t pay bills, I wanted to be able to write in other forms to eventually afford my rent. For the most part, I have done this. My ambition, at times, has been white-hot, and there are moments when I feel I am not where I need to be, though I am very happy with my life. I have managed to be more content in my early thirties than in my twenties, which was a time of great joy, occasional tumult, and mild anxiety, the sort that seizes you when you’re on the subway, a morning commute out of Sheepshead Bay on the B, and says you’ve yet to measure up to some mythical yardstick. You haven’t published there, you haven’t gotten that book deal, you’re still working where, exactly? And on and on. That has mostly left me, and I am grateful.

(By the way, if you’re reading this far, you probably love books so please consider pre-ordering my novel, which is out on Feb. 1, 2022. If you’re an audiobook person, there will be one available too.)

I chart the years through books. Since the end of 2015, I’ve tracked every book I’ve read. In 2020, I brought my year-end tradition from Medium to Substack. In the past, I would assign grades to books but I decided to end the practice. Grades are arbitrary on their own and grading books is more subjective than even that. Instead, what I like to do is write about some of those that I enjoyed or found notable, and post the list for you at the end. For the first time since I tracked my reading, I read fifty books. The pandemic era, for me at least, has meant far more time to read.

I don’t set out, in a given year, to read certain types of books. I meander, moving between new releases and books decades-old, saving more time for fiction but enough for biography, history, or anything else. I take recommendations.

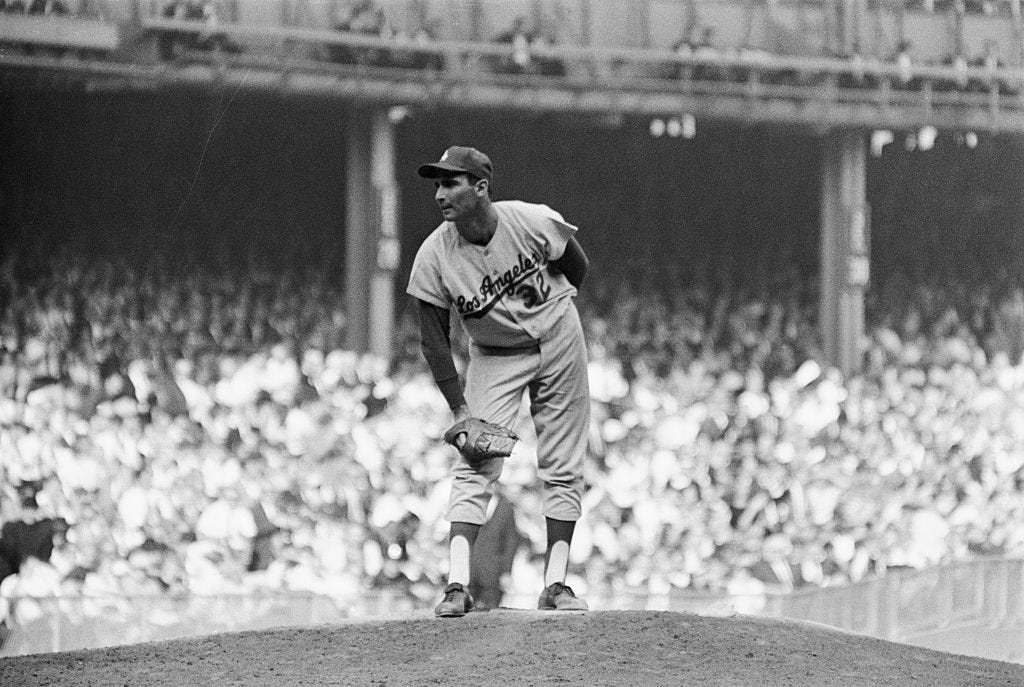

This year, I happened to read a few biographies. There was, notably, Jane Leavy’s A Lefty’s Legacy, the definitive Sandy Koufax biography which, for reasons unclear, I had never read until now. As a Jewish baseball fanatic from Brooklyn—a left-hander to boot—it was impossible for me not to care about Koufax. (This piece is being published on December 30th, Koufax’s 86th birthday.) The Koufax mythos is of the kind that, in the twenty-first century, cannot really be approached again. For those who don’t know, Koufax was the second great Jewish baseball star after Hank Greenberg, one of the top sluggers of the 1930s and 40s. Koufax, a left-handed pitcher, dominated baseball for five seasons, all of them in technicolor Los Angeles, almost single-handedly dragging the Dodgers to two World Series titles in 1963 and 1965. For that short period, he had no peer. Koufax pitched at a time when television was new, the playoffs meant the World Series, and baseball had little competition in the American imagination. He missed a World Series game for Yom Kippur, only to later win the deciding game 7 on two day’s rest—becoming, for all time, a baseball folk hero. Pitching through horrific arm pain, Koufax shocked the world when he retired after the 1966 season, at the age of 30. In his retreat from the public eye, some compared him to Salinger, but Koufax was always happy to show up at Dodgers spring training. He was a quiet man who preferred his privacy, and there is almost nothing in Leavy’s biography about Koufax’s personal life. We live on the field with him, where his rocket fastball and hammer curve humbled hitters in the early 1960s.

The picture above was taken in 1963, when Koufax, in game one of the World Series, struck out fifteen Yankees at Yankee Stadium, including the first five batters. It was the first World Series game the Dodgers had played in Yankee Stadium since leaving Brooklyn following the 1957 season. The Yankees had won the World Series in 1961 and 1962, and knew little of the young Koufax, who pitched in a different league. “I can see how he won twenty-five games,” Yankees legend Yogi Berra said after Koufax crushed them in game one. “What I don’t understand is how he lost five.”

That 1963 game has a few literary threads. In the movie version of Ken Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, R.P. McMurphy, played by Jack Nicholson, tries to watch this very World Series in the mental institution. Nurse Ratched cruelly denies him. Undeterred, McMurphy decides to narrate the game on the blank television, inventing an alternate reality. “Koufax kicks, he delivers, it’s up the middle, it’s a base hit, [Bobby] Richardson is rounding first, he’s going for second, the ball’s into deep right center, [Willie] Davis over in the corner to cut the ball off! Here comes the throw, Richardson rounding first and he goes into second and he slides and he’s safe!” McMurphy shouts. “Koufax is in big fucking trouble, big trouble baby!” By now, all the patients have rallied around McMurphy, entranced by his narration. “Koufax’s curveball is snapping off like a fucking firecracker. Alright, here we come with the next pitch and Tresh swings, it’s a long fly ball to deep left center, it’s going, it’s going, it’s gone!” Next up, McMurphy says, is Mickey Mantle. “He swings and it’s a fucking homerun!” His fellow patients erupt with joy. It should be noted that Tresh, indeed, did hit a two-run homerun off Koufax, but it came in the 8th inning when the game was out of reach. Mantle, though, was 0–3 against the great left-hander.

In Blake Bailey’s fascinating and frustrating biography of Philip Roth, which I also read this year, the 1963 game comes up again. Roth, who was then thirty, was in attendance to see the fellow Jewish superstar. It was one of his most cherished baseball memories. And in my first novel, published in 2018, I have a protagonist who bets against Koufax at the start of the World Series, assuming the Brooklyn boy would wilt under the pressure of facing the mighty Yankees.

Ultimately, as was written elsewhere, the trouble with Bailey’s biography—he would face allegations of rape and sexual abuse after the book’s publication—was that it indulged far too much in tedious gossip and invective, per Roth’s instructions. Roth had sought out a willing biographer to quite literally settle his scores with almost everyone, from literary rivals to ex-lovers. Bailey’s Roth biography manages to be, at times, deeply entertaining—a point in its column, because literary biographies can be slumber-inducing. But it demeans, thanks to Roth’s own meddling, the subject himself, skimping on literary analysis and needlessly cataloging, in relentless detail, a tumultuous sex life. You will, quite literally, learn in this book about everyone Roth slept with throughout his eighty-five years. Roth is, indeed, one of America’s greatest writers, a master deserving of his accolades, and the biography does not do his oeuvre justice. Much of that is Roth’s own fault, since he aggressively stage-managed the production before his death in 2018.

I was fortunate to read several great works of fiction and nonfiction this year. The novelist Christopher Sorrentino published a powerful memoir, Now Beacon, Now Sea about the confounding relationship of his parents, Gilbert and Vicki Sorrentino. Gilbert was an exacting, brilliant avant-garde novelist and poet from my own neighborhood of Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, and a childhood friend of another well-known Bay Ridge novelist, Hubert Selby Jr., who wrote Last Exit to Brooklyn and Requiem for a Dream. Christopher’s mother, Vicki, is the real heart of the memoir. A fierce woman who increasingly retreats from society as the decades pass, she is a riddle her son strains to solve. He discovers her decaying corpse in her Bay Ridge apartment, where she had died alone. How does she end up there? Probing his own upbringing on the Lower East Side and later California, where Gilbert taught at Stanford, Sorrentino plumbs the depths of a marriage, puzzling over how his parents stayed together and if they shared love at all. The memoir is haunting, and one of the very best I’ve read.

An autodidact who never graduated college, Gilbert Sorrentino would be hired as a professor of English at Stanford in the early 1980s over the strenuous objections of Wallace Stegner, the so-called dean of Western writers, the man who ran the famed Stegner Fellows program there. Kesey of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s fame was a Stanford student who also clashed bitterly with Stegner, who did not approve of the budding psychonaut. With Sorrentino and Stegner, it was very much East vs. West, with Stegner growing bilious and irrational in a war he would eventually lose. But Stegner could absolutely write. This year, on recommendation, I read his masterpiece, Angle of Repose, a lush novel teeming with what constitutes a certain kind of life. For a week or more, I plunged into the American West, to places I had never been, and poignantly into two periods now long receded—the late 1800s and 1970. Stegner is an acutely atmospheric writer. To render the natural world in effective language—in language that is not well-trod, trite, forgettable—is rare, and it was with Stegner while I was in Brooklyn that I felt I, too, had seen all these places: the Grass Valley, Leadville, the desert canyon, Mexico, dreary Boise. More than that, Angle of Repose is about the limits of a marriage, of continental yearning, of the civilizational concrete pitted against the wild ambitions of the counterculture. Based on the life of Mary Hallock Foote, the novelist and illustrator, and narrated from the perspective of the fictional Stegneresque historian Lyman Ward, Angle of Repose is very much a book after what it meant, at one time, to be an American alive at a time of startling growth and rupture.

I read many other intriguing books this year. They include Up in the Air by Walter Kirn, who is DeLillo for the skies—and the book is far, far better than the film. Kirn’s sentences glide in the best way. I wrote in the summer about Joshua Cohen’s The Netanyahus, and how it speaks to my own Jewish identity. Unlike others, I thought Percival Everett’s The Trees was somewhat unrealized, but both So Much Blue and Telephone are tightly-sketched masterpieces. If not for its noirish swerve in the final third of the novel, Atticus Lish’s The War for Gloria would’ve been a masterpiece too. Oddly, I had just finished Joan Didion’s final collection, Let Me Tell You What I Mean, when I learned she had died. There isn’t much I can say here that hasn’t been said elsewhere about a twentieth century titan. A little over a year ago, I wrote about her splendid takedown of Bob Woodward. And yes, you should absolutely read Cynthia Ozick’s The Puttermesser Papers.

Without further ado, the books I read in 2021, not ranked but simply in the order I read them:

1. Dead Astronauts by Jeff VanderMeer

2. Money by Martin Amis

3. Zeroville by Steve Erickson

4. Slow Vision by Maxwell Bondenheim

5. The City Life by Pete Axthelm

6. Sandy Koufax: A Lefty’s Legacy by Jane Leavy

7. Fake Accounts by Lauren Oyler

8. London Fields by Martin Amis

9. Assume Nothing: A Story of Intimate Violence by Tanya Selvaratnam

10. The Queen’s Gambit by Walter Tevis

11. The White Album by Joan Didion

12. Widow Basquiat by Jennifer Clement

13. Bubblegum by Adam Levin

14. Convenience Store Woman by Sayaka Murata

15. New York, New York, New York by Thomas Dyja

16. The AOC Generation by David Freedlander

17. Ghosts of New York by Jim Lewis

18. Telephone by Percival Everett

19. Hate Inc. by Matt Taibbi

20. The Deep End: The Literary Scene in the Great Depression by Jason Boog

21. No One Is Talking About This by Patricia Lockwood

22. The Puttermesser Papers by Cynthia Ozick

23. The Netanyahus by Joshua Cohen

24. The Cult of Smart by Fredrik DeBoer

25. Paul Simon: The Life by Robert Hilburn

26. The Other Black Girl by Zakiya Dalila Harris

27. Philip Roth: The Biography by Blake Bailey

28. Making It by Norman Podhoretz

29. So Much Blue by Percival Everett

30. Sensation Machines by Adam Wilson

31. Something New Under the Sun by Alexandra Kleeman

32. Now Beacon, Now Sea by Christopher Sorrentino

33. Friday Black by Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah

34. Weather by Jenny Offill

35. The War for Gloria by Atticus Lish

36. The Trees by Percival Everett

37. To An Early Grave by Wallace Markfield

38. Leave the World Behind by Rumaan Alam

39. Up in the Air by Walter Kirn

40. Crossroads by Jonathan Franzen

41. Oh William! by Elizabeth Strout

42. Ghosting the News by Margaret Sullivan

43. Angle of Repose by Wallace Stegner

44. How Lucky by Will Leitch

45. A Splendid Intelligence: The Life of Elizabeth Hardwick by Cathy Curtis

46. Sag Harbor by Colson Whitehead

47. Sleepless Nights by Elizabeth Hardwick

48. Prime Green: Remembering the Sixties by Robert Stone

49. Let Me Tell You What I Mean by Joan Didion

50. Territory of Light by Yūko Tsushima

Angle of Repose is good. But I think The Big Rock Candy Mountain is better. If you like Stegner and haven't yet read it, I highly recommend it.

excellent list