My 2022 in Reading

Falling into the last century

In a cold, driving rain, I made my way on the Belt Parkway. The traffic, in the December darkness, was typical, and I let the brake lights taunt me. Since I was hours from the Paramount, a theater in the Long Island town of Huntington, I could settle in and allow my mind to drift. I do some of my best thinking in the car. I’ll dream up future ideas, begin writing pieces in my head, and tour old memories. Since I knew I had left enough time before the concert, I could enjoy the music coming through the car speakers; I’m at my best as a listener when relaxing. Much of my antic energy—what’s inevitable when traffic swells and I have somewhere to be—left me. Summer Days (And Summer Nights!!) was playing straight through.

I was off to see the Beach Boys, or what passes for them in the final month of 2022. Two living members tour with the group. Two others, including their founding genius, are exiled. All of the members are at least 80. It was my first time seeing this version of the band. In 2016, I watched an elderly Brian Wilson and his backing band sing from Pet Sounds, not really understanding what was in front of me at McCarren Park in Brooklyn. I was a Beatles kid, a Velvet Underground kid, a Simon and Garfunkel kid, an Animal Collective kid. Who was Brian Wilson? Who were the Beach Boys, really? Kitsch, maybe, and not a band I would bother with to any serious degree. As I wrote earlier this year, I would grow to be Beach Boys obsessed—you should read the essay to understand why—and part of that obsession meant reading whatever I could about the band. Unlike the enormous amount written on the Beatles, it’s fairly easy to tackle the Beach Boys bibliography. I read three of the seminal works this year: Steve Gaines’ Heroes and Villains, David Leaf’s updated California Myth, and Peter Ames Carlin’s Catch a Wave. All have their strengths and weaknesses. Gaines is far more interested in the band’s lurid personal failings and financial minutiae than the music itself, but he’s the best writer of the bunch. Leaf offers a pure fan’s point of view—in later years, he would become a close personal friend of Brian and help him finish Smile—and gets credit for pioneering studies of the Beach Boys. Carlin wrote what is the best professional biography of Brian and the band, striking a proper balance between an appreciation of the transcendent music and the inevitable cataloging of cash lost, drugs consumed, and families ruined. (I’ve since ordered Tom Smucker’s Why the Beach Boys Matter—I was thrilled to find out he’s a reader of this Substack!—and I’ll consume it in the new year.)

By the time I reached the concert in December, I was something of an expert. I was also an outlier there, a 33-year-old man sitting alone in a sea of Baby Boomers. (My girlfriend passed on going, as did a friend.) I tracked the set list, understanding I’d probably not get to see some of my favorites, like “Surf’s Up” or “‘Til I Die” or “Let Him Run Wild” or “Girl Don’t Tell Me.” Mike Love, rival to the deceased Dennis Wilson and the exiled Brian, runs the show, and this inevitably means certain songs will get left off. Mike sings well for 81, but he is 81, and I wasn’t entirely sure Bruce Johnston was really playing the keyboard. (There’s a certain irony to Johnston being a part of the touring Beach Boys when the band never played his songs, including “Deirdre” and “Disney Girls.” The crowd, which probably stopped listening to new Beach Boys music in 1966 or so, did not react much when the band played “It’s O.K.,” a catchy single that made it as far as number 29 in 1976.) John Stamos, of Full House fame, put in an appearance, drumming and guitaring and singing his inferior version of “Forever,” the Dennis classic. The Beach Boys have an extensive backing band and they are all very good at what they do; the somewhat anonymous guitarists hit the falsettos the two living band members can’t get near. Overall, the show was fine, if it only left me longing more for what I never would have: the full band in front of me, each man not yet 30, knocking out the hits and obscurities in all their glory. What a treat it must have been to see the Beach Boys in 1963 or 1971. I asked for Carl and Dennis to rise from the dead. I thought of Kilgore Trout, at the end of Breakfast of Champions, shouting “Make me young, make me young, make me young!” into the void.

This was quite a wind-up, I know. Every year, I make a list of all the books I read and offer my stray thoughts. I’ve done this every year since 2015. I’m a writer and every writer must read. There is no other way. This year, I wrote on the importance of reading and writing about books. This year, I also published my second novel, which you should buy. There’s another one on the way, the best thing I’ve done, that I hope gets sold soon.

The best novel I read in 2022 was Zain Khalid’s Brother Alive. Khalid is just 32, and I feel that in another era Brother Alive would have been much more heralded, the sort of novel borne aloft on a relentless publishing and publicity machine. I was disappointed to find it ignored by the New York Times’ coveted year-end lists, beat out by much inferior works. I think Khalid is a major talent and Brother Alive should have been nominated for any of the top literary awards. Khalid’s work, which leaps from Staten Island to Saudi Arabia, is something of a multicultural systems novel, DeLillo hustled to Jumu’ah prayers, and manages to interrogate, with kaleidoscopic precision, the fallout of 9/11, queer sexuality, and the father-child bond. Rather than offer a plot summary—there’s a gas that is supposed to inculcate faith, though it comes at the expense of physical and psychic unraveling—I’ll urge you merely to read it. I await Khalid’s next offering and hope for more novelists like him to break through soon. If the culture around cinema and music has gone static, strangled either by MCU films or poptimism, books still offer a rejoinder for those willing to put in the time to hunt out treasure.

I wrote three essays on four excellent nonfiction books I read this year: Jarett Kobek’s twin accounts of his chase for the Zodiac killer and the darkness behind the California myth, Jonathan Rieder’s The Jews and Italians of Canarsie Against Liberalism, and Matt Sienkiewicz and Nick Marx’s That’s Not Funny, an examination of the conservative comedy complex. I hope, in January, to have a piece here on Bret Easton Ellis’ first novel in 13 years. I read the galley of The Shards in October and was, at the very minimum, impressed.

Other recommends include my friend Lincoln Mitchell’s San Francisco Year Zero, a fantastic account of San Francisco in the 70s under George Moscone. Mitchell was a big help as I wrote about the downfall of Chesa Boudin, the progressive San Francisco district attorney, for New York Magazine. Christopher Sorrentino’s Trance, which was a finalist for a National Book Award in 2005, was another great find, an ambitious novelization of the Patty Hearst saga. Jesse Jezewska Stevens’ The Visitors proves she is another young novelist to watch. And finally, Elizabeth Hardwick’s essays are of a rigor and splendor that is far too absent in the age of internet writing. Darryl Pinckney’s memoir of his friendship with Hardwick is a worthy trip to a vanished world.

Without further ado, here’s everything I read in 2022.

1. The Group by Mary McCarthy

2. Motor Spirit by Jarett Kobek

3. How to Find Zodiac by Jarett Kobek

4. An American Dream by Norman Mailer

5. Liberalism at Large: The World According to the Economist by Alexander Zevin

6. The Glass Hotel by Emily St. John Mandel

7. Olga Dies Dreaming by Xochitl Gonzalez

8. Trance by Christopher Sorrentino

9. Red Pill by Hari Kunzru

10. Maus by Art Spiegelman

11. Too Good to be True by Benjamin Anastas

12. The Nineties by Chuck Klosterman

13. Low Life: Lures and Snares of Old New York by Luc Sante

14. That’s Not Funny: How the Right Makes Comedy Work for Them by Matt Sienkiewicz and Nick Marx

15. The Fugitives by Christopher Sorrentino

16. Canarsie: The Jews and Italians Against Liberalism by Jonathan Rieder

17. Overthrow by Caleb Crain

18. San Francisco Year Zero: Political Upheaval, Punk Rock, and a Third-Place Baseball Team by Lincoln Mitchell

19. A Walker in the City by Alfred Kazin

20. The Visitors by Jesse Jezewska Stevens

21. The Employees by Olga Ravn

22. 2 A.M. in Little America by Ken Kalfus

23. Raising Raffi: The First Five Years by Keith Gessen

24. The End of Me by Alfred Hayes

25. Perfect Tunes by Emily Gould

26. Lost in the Meritocracy: The Undereducation of an Overachiever by Walter Kirn

27. Uncanny Valley by Anna Wiener

28. Heroes and Villains: The True Story of the Beach Boys by Steven Gaines

29. Blood and Guts in High School by Kathy Acker

30. Heartburn by Nora Ephron

31. The Great Believers by Rebecca Makkai

32. The Beach Boys and the California Myth by David Leaf

33. Brother Alive by Zain Khalid

34. I’m Glad My Mom Died by Jennette McCurdy

35. The Shards by Bret Easton Ellis

36. Less Than Zero by Bret Easton Ellis

37. Come Back in September: A Literary Education on West Sixty-Seventh Street by Darryl Pinckney

38. Catch a Wave: The Rise, Fall, and Redemption of the Beach Boys’ Brian Wilson by Peter Ames Carlin

39. The Answers by Catherine Lacey

40. Feral City: On Finding Liberation in Lockdown New York by Jeremiah Moss

41. No One Left to Come Looking for You by Sam Lipsyte

42. The Uncollected Essays of Elizabeth Hardwick by Elizabeth Hardwick

43. The Vixen by Francine Prose

44. Pure Colour by Sheila Heti

This is a great site - FdB recommended it and I can see why.

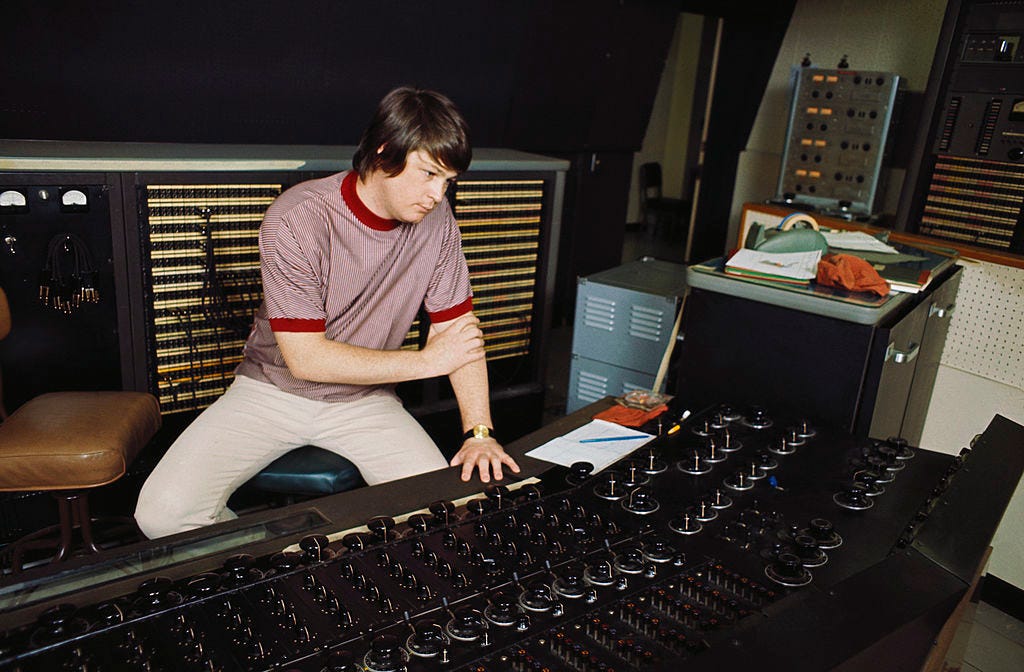

I was wondering why I was looking at a young Brian Wilson on the home page - now it makes sense.

Try Celeste Ng Our Missing Hearts and St John Mandel’s most recent Sea of Tranquillity