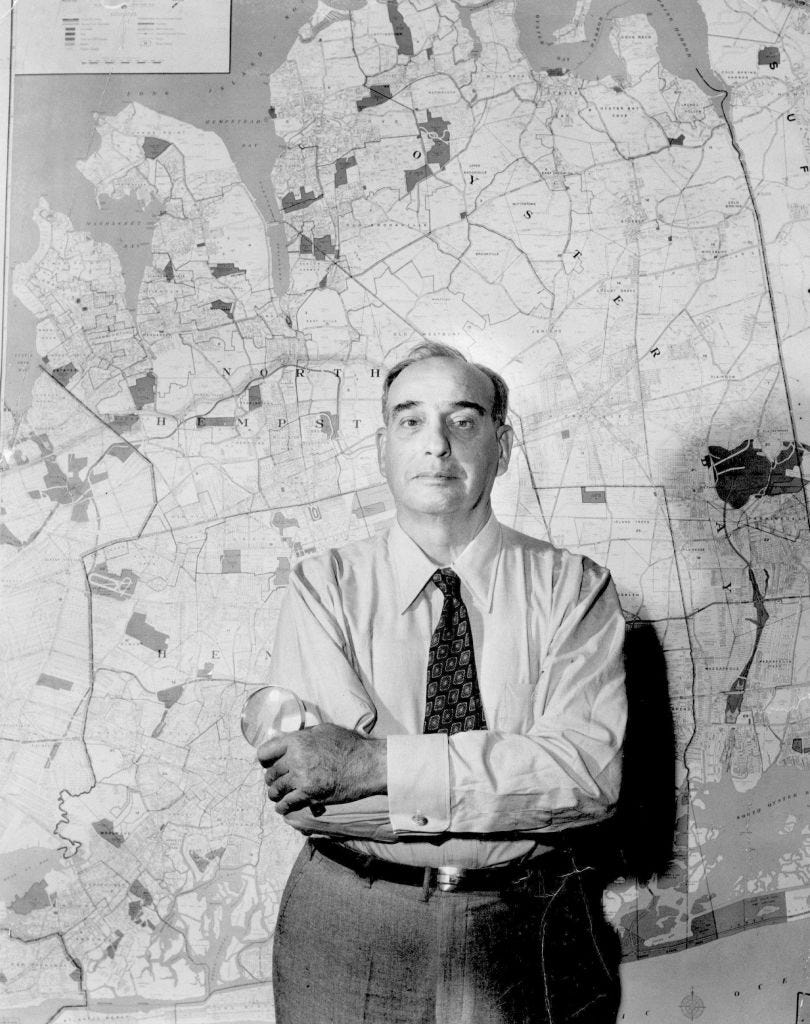

Robert Moses and Racism

An aside on "The Power Broker"

I was excited to publish a piece in the Times this week arguing for a reassessment of Robert Moses while critiquing how The Power Broker has been read and consumed. Robert Caro’s biography, now a half century-old, deserves its accolades, if it represents a somewhat flawed and dated way to view New York City. If I had to boil down my qualms with Caro’s reporting and research, it would be his drive for narrative sweep at the expense of context. The Power Broker does not study the development in other cities that happened almost simultaneously. Moses was obsessed with highways and expressways at the expense of mass transit, but so were most urban planners across America as the twentieth century wore on. Expressways ripped apart major and midsized cities in a manner that even Moses, in Manhattan, could not make possible. Caro invests a bit too much in the Moses mythos—yes, there are projects like Jones Beach and Flushing Meadows and Lincoln Center and the United Nations that are completely him—without doing much to acknowledge that the Regional Plan Association had sketched out a vision for highways in New York that he mostly implemented rather than imagined himself. There is also the challenge Caro could not avoid: his book was published in 1974, when New York was on the brink of fiscal insolvency. All the ills of the city sure seemed like they were caused by Moses, when in retrospect we know they were not. Moses did not trigger the collapse of the city’s manufacturing sector or mismanage the municipal budget. He did not tell the bankers to stop lending money to the city and he did not usher in the neoliberal age. He did help, through suburbanization, contribute to white flight, but this is another trend, like the rise of the automobile, that would have occurred had Moses never been born. As I wrote in Compact, we need, for better ends, some of that Moses-style ambition today.

Was Moses a racist? Probably. He was born in 1888. He was white. I have no doubt he said racist things, as Caro has reported. I am far more doubtful that his racism actually showed up in his urban planning or that there’s real proof race was baked into his decision-making. Moses was the definition of an equal opportunity offender. He was going to build where he liked, and damn the opposition. It really did not matter to him if the neighborhood getting disrupted was white, Black, or Puerto Rican. In fact, since New York, in the era of Moses—from the 1920s to the 1960s—was a largely white ethnic city, almost every infrastructure project of note did impact white neighborhoods. His Cross-Bronx Expressway horrified Jews in East Tremont. His Brooklyn-Queens Expressway alienated Norwegians and Irish in Sunset Park. His Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge robbed homes from Irish and Italians in Bay Ridge. Even the urban renewal project around San Juan Hill in Manhattan—the construction of Lincoln Center and attendant housing—was chasing out white ethnics, along with Puerto Ricans. I doubt, when it came to Jones Beach, Moses wanted lower overpasses to keep buses of Blacks and Puerto Ricans away because there simply weren’t many of them when Jones Beach was built. Again, New York was dominated by white ethnics, and this would only begin to shift in the 1960s. Moses disliked mass transit; he believed in the concept of a parkway, where the automobile would glide seamlessly without bulky trucks and buses hovering about. This was lousy urban planning, but not race-driven.

Then there are the monkeys. I had a section in my Times piece about them that was cut for space. The Power Broker strongly hints that Moses purposefully placed a trellis adorned with long-tailed, possibly shackled irony monkeys outside a playground bathroom in Harlem to taunt locals who were Black. A social media campaign eventually got them removed. There were several problems with this story, though. Despite Caro’s claim in the book, monkeys do appear in another portion of Riverside Park, in a playground on W. 83rd Street in the predominately white and affluent Upper West Side. The Harlem playground, situated on W. 148th Street, was closest to West Harlem, a neighborhood that was largely Irish, Italian, and Greek in the 1930s and 1940s. The Census shows this.

The oddity of the section about the Harlem playground in The Power Broker is how small it is—barely two paragraphs in a famously enormous and meticulous book. Caro offers no direct evidence for Moses placing the monkeys there as a way to insult or intimidate the Black community. Caro merely winks at it and moves on. It’s a shockingly sloppy section that reads like gossip. Or, it reads like the work of a newspaperman, not a historian. Caro bases most of his excavation of Moses on documentation, but here no documents arise. Most of the writing on Moses’ racial attitudes derives from interviews with men who knew him but not on the actual written documentation Moses produced—and Moses, a prolific writer of letters and memos, left behind a formidable paper trail. It’s a paper trail that’s required to prove the urban planning decisions Moses made were based on racial animus. Where are those documents?

This doesn’t mean Moses should be sanctified. It doesn’t mean Moses didn’t make profound mistakes. It doesn’t mean Moses wasn’t an elitist—an elitist who, it must be said, built a tremendous amount of housing for the working class—or a self-hating Jew, or said nasty things about people who didn’t look like him. It means, rather, his legacy remains complex and contested, and it will never be easily summed up.

I understand you probably didn't write that Times headline. But honestly it was one of your weakest pieces of writing. The alleged egregious errors of Caro's never seem to actually materialize, and you are grudgingly forced to admit that actually he does give Moses plenty of credit for the positives.

Moses’s origins were in the Progressive Era. The Progressives with a capital P had views about how to make society better. So, sure, we want the poor out of tenements. But we, the educated class, know what’s best for them, how they should live, what they are entitled to, where they are not welcome. Who are they to complain or state their opinion? This is a whole lot different from complaining about NIMBY.

To me, the most revealing story in the book ( besides those Parkway bridges) was the decision - when he was running out of money - to just pound the Henry Hudson Pkwy through Harlem and Washington Heights with no real parks at all - just the bare minimum for the working class.

BTW, Caro gets wrong the placement of the HHP even further uptown. He doesn’t like that Moses cut it through Ft. Tryon and Inwood Hill parks, where they are (in fact) virtually invisible. He wanted Moses to run it up Broadway - where it would have cut off access to the parks So Caro has a particular narrative, and he puts the pedal to the floor to tell it. Is he always a “trustworthy narrator?” No. But we can call out where Caro goes wrong and still see his critique of Moses’s perspective as fundamentally on point.