Teddy Starr, All-American

New fiction

In April, my new novel, Colossus, arrives. Dana Spiotta, National Book Award finalist, describes it this way: “The slick, rich, right-wing pastor Teddy Starr is a charismatic confidence man in the American vein (part Elmer Gantry, part Jay Gatsby, part Donald Trump). As fast talking as he is, as amoral as he is, Barkan gives him a fascinating, complex inner life. This thrilling novel skewers the cynicism of our current moment, but it also strikingly renders the human drama of fathers and sons, the tension between legacy and possibility.”

Normally, I’d leave it there, and tell you to the preorder Colossus. But I’ve got a special treat: an excerpt from the actual novel. You will get to meet Teddy Starr. Teddy is a pastor and local real estate tycoon, the king of his rural Michigan town. And he’s got a dark secret. Today, you’ll follow him along on one of his daily adventures, where he gets to see a woman who is not his wife.

Today is May 3, two days after the first of the month. For anyone in real estate, that day looms with all its hope and dreadful opportunity. The hope, if you’re in my shoes, is obvious enough, and the dread comes, naturally, from not being able to collect when you should. I consider this, driving alone, farmland sprawling on each side of me. The roadway unnerves me, though I’ve never admitted this, even to Daniella. A two-lane east-west artery, it pits you against oncoming traffic at all hours, typically trucks and campers hungry to make good time on whatever expedition has taken them out into roaming country. One wrong twitch or wince and you’re over the double yellow and into the grille of a much larger, possibly faster vehicle, your bones mashed in with the hot, twisted steel. I’ve played out this scene many times in my mind—the exploding glass, the bursting blood, lithe EMTs swarming my long-dead body. There’s an assumption that a pastor can’t fear death, and that’s just not true. I’m comfortable with where I’m going, but I’m not, necessarily, in any hurry to get off this Earth.

It’s true that in one sermon, I said just the opposite. It was six months ago, trending into Christmastime, and I wandered onto an anecdote about happy Christian funerals. My contention, which was well received by the church, was that you won’t see as many tears and frowns and crinkled expressions at truly Christian funerals. There is outward joy, not sadness, because the dearly departed loved one is now going to meet Jesus. There can only be so much to lament, I said, because so much love awaits you. This was, in no way, an endorsement of death or what they might call suicide ideation—it was an observation worth making. When you believe, you secure an inner peace that can deliver you through the worst of life, a belief that slowly strips your fear away.

Fear, though, is on tap for a bit longer, until I can veer off onto East Putnam and drive the three miles to the Breckenridge homestead. Daniella has Chloe and Austin at home. Theodore Jr. is on a playdate—well, he’s too old for it to be called that, but that’s what I still think of it as—with Garrett Hannon, Brendan’s second oldest, and they’re probably knee-deep in cheese puffs and ice cream, playing lurid video games on Brendan’s forty-three-inch LED, F22 Series, smacked snugly against the oaken side wall of his supremely finished basement. A house I sold to him, which was no easy feat given that Brendan’s credit and cash flow were a bit more tenuous than expected, at least in those days. This was before his promotion at E&I that vaulted him gracefully two tax brackets upward. Now he entertains my oldest in style, and I drive alone to repair a leak. At least that’s what Gertrude called it over the phone.

I approach East Putnam slowly, sure not to yank my Chevy too far to the right, lest I hum into a muddy ditch and start kicking up dirt on a road barely large enough for my four-door. Dust clouds dutifully swirl, hanging like dragon breath, and I click my tongue, an old habit. If you’re conscientious around here, you’re taking your automobile in for a weekly deep cleaning, and I’m six days out from my last trip to Chip’s Wash on Huron. Time to get on with it and I wish I weren’t approaching the Breckenridge homestead in such a soiled vehicle. I like coming out here with a gleam, a near sparkle, and I can only imagine what the cold-blue swabbed Chevy would look like under a heavy late afternoon sun.

It’s a straight shot on East Putnam, past two glum intersections, corn flanking me on all sides. There’s nothing quite like the high after a good sermon, the trace it leaves in your mouth and stomach. It must be something like the buzz of a ballplayer, a job well done, a synchronicity that nearly transcends words.

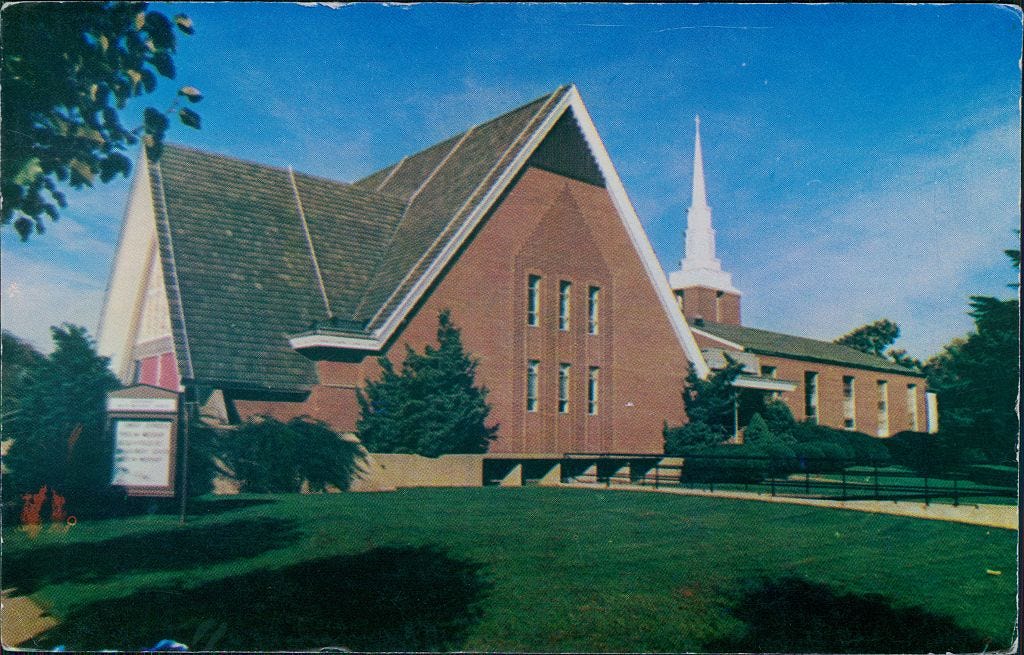

Driving through the country has reminded me I don’t want to live in the country. I am glad Trinity of Pine Haven is situated on prime real estate near the college, that the founders had the wisdom to build near a secular liberal arts institution. If they resented the godlessness of Pine Haven—that’s the college, neatly named for the town—they at least understood, intrinsically, it made most sense to own tax-free land two streets away from its outer border. I don’t like the overt emptiness of the country and the darkness that encroaches.

Lonely farmers, even those engrossed in prayer, are a particularly mournful lot to me, and I wish they could all congregate nearer the warmth of a municipality—a city in the technical bureaucratic sense, a town to anyone who is functioning there—that will remain around nine thousand until Jesus Christ’s return. The country here is stripped of hills, of right angles and jagged edges on the horizon, and the flatness in twilight can bring a man real low, like he’s soil-bound in the face of a starshine he’ll never reach.

In town, I know where I am. I know it teleologically. I know I am closer to God there, too. It is why, as much as we may pray alone, we’re ultimately bunched like bugs on Sunday, clustered under one roof. I don’t want to preach to myself, but here, in the corn, that’s all you can do. You collapse into your homestead.

Gertrude hasn’t succumbed to this, but poor Harry has. Harry, now laid up in Luce Memorial, that staph infection taking a nasty but manageable turn. He’s four months younger than me, thirty-nine teetering on forty, and I know he doesn’t want to start a new decade this way. I’ve gone three times to visit him there, where he’s now sequestered in a stepdown unit with an ornery roommate, a fiery seventy-year-old Episcopalian from Mount Pleasant who’s recovering from a heart attack. Harry has a television he can stare at straight above when he adjusts his bed just right and the last time I was there, he was intently watching a Jeopardy! rerun.

He wants, more than anything else, to get back to his farm, where work can drown out all the noise that comes with merely existing. They have one child, Aidan, who’s thirteen and already liable to wander; there’s a scissor-flash in his eyes and I don’t trust him very much. He’ll mutter about wanting to beat it from Pine Haven altogether, though there will be no better place for him, nowhere that will ever care so much for his future. Harry, at least, has chosen to recede into the life he has, while Gertrude, with limitations, ranges about. She drives into town every weekday to sit in the admissions office at Pine Haven College, answering telephones with two other ladies. And if Aidan hasn’t already, he’s probably planning on getting into drinking, and fornication isn’t far off. When I pull into the homestead, I figure this will come up and I’ll need to prepare comforting words for Gertrude.

Soon, the big red farmhouse looms. I’m close. Dust swirls again and a pheasant, a highly decorated male, skirts overhead.

My automobile is making a kerplunking noise I don’t especially like and I take note, to get it looked at before next week. I inch up the rambling driveway, spotting two well-fed cows and a gelding beyond a picket fence. One of them is named Fredrick, and I forget if this gelding, the color of chocolate left in the sun, is him. Harry’s truck and trailer are farther up the driveway, as well as Gertrude’s Wrangler. All the vehicles are parked slightly askew, as if a microburst had tossed them around a bit, and I chalk this up to country folk ways I’ll never quite understand, no matter how much I come here. I park far enough away to give the Wrangler a wide berth for escape; suddenly, I’m assuming it has a mind of its own.

There are no doorbells on the homestead and Gertrude isn’t one for texts. I’m here won’t suffice. I knock on the soaring wood door twice, hearing my own echo and enjoying the feeling of skin in hard contact with material that long predates me. The homestead was built by Harry’s maternal great-grandfather in the 1910s and it’ll have to be Aidan’s someday. A child, always a son, has inherited it, and Aidan can only flee his birthright for so long. Kings abdicate, but not farm boys due their treasure. Land, excepting God, is the greatest lure. I listen for Aidan’s potential pitter-patter, hoping he’s not home, and hear nothing as I wait on the cramped porch, which was grafted onto the two-story some decades ago.

Sounds behind the door, a solitary two-step, and I know I’m fine. In my right hand, I have my leather pouched tool kit, good for fixing the kind of penny-ante kitchen sink leak Gertrude needs help with today. I dabble in minor repair work. I would never call myself handy or pit my limited skill set against the men with round, firm guts who tinker away weekends on their F-150s and craft their own hunting blinds, but I’d like to think, here anyway, I can hold my own. A man has to know what to do with his hands, particularly in a world like this one. Daniella likes that I can install showerheads and lay tile. None of this was taught, just as the men vanished beneath the undercarriages of their F-150s had to learn most of what they do on their own unless they were blessed with daddies who took the time to helpfully guide their grease-soaked hands.

“There you are,” Gertrude says when she opens the door. I peer behind her briefly, checking to make sure that there are no sounds of a wayward son.

“On time, just through the dust clouds.”

“You always hurry when you’re needed. And you’ve got a bit of sweat on your brow already. It was supposed to hit seventy today, but never did.”

“Weathermen deceive, or they talk out of ignorance. I still find comfort in them, though. I wait for the five boxes. Monday partly cloudy, Tuesday chance of rain, Wednesday clear, humidity inching up. I feel you can set your watch to it, even when it isn’t right.”

“You want facts for facts’ sake. Even when the facts are incorrect.”

“I do think we’d all be calmer if we all agreed to collectively watch the weather forecast every night.”

“We’d be calmer if the television told us all what it really thinks.”

I follow her inside, enjoying the lightest jousting, what’s possible when two people are alone and allowed to perform. At church, a crowd (a lovely one), and at home, another, also lovely, three children, a wife who is languorous until she isn’t, and a stack of bills always hitting our kitchen table. None of that here, in Gertrude and Harry’s shadow-sunken foyer, smelling lightly of sandalwood.

In here, the sunlight dribbles in just right through the leaded glass windows, leaving a wide, crescent-shaped pool on the grand piano. Our feet creak over the hardwood, no carpet anywhere, and I’m grateful for the sound. We make way for the kitchen.

“How is Harry?” I ask, straining to summon up worry.

“Harry is complaining about the food. He thinks Luce Memorial wants to poison him to keep him there indefinitely, to soak him dry and steal the homestead.”

“That would be quite the scheme. Workable, in some sense.”

“I’m going to see him before it gets dark. It’s best visiting him at that time of day.”

Gertrude is a crisp, trim thirty-six, her dark brown hair slashed at the shoulders, her eyes a curious milky hazel. Her name belies who she is and what she looks like: even around here, she’s the only Gertrude under sixty, and neither of the surnames she’s possessed in this life—Howell, the maiden, or Breckenridge, the married—lend any credence to her relative youth. She’s never Gertie, either. She and Harry joined the church four years ago and have been regular attendees since, Gertrude’s devotion increasing over the past year. That’s when she joined Bible study.

“Let’s see that leak.”

Gertrude is dressed for a run. She’s the only person I know of who jogs the country roads, risking her life on choking dirt and gravel, no shoulder to dip into, drivers comfortably lured into committing manslaughter. Right now she’s in dark Lululemon high-rise track shorts and a sleeveless Nike top, her upper arms thin and lightly toned. I can’t tell if she’s about to run or has already.

Exercise or not, she doesn’t seem to sweat. That’s its own talent.

“I don’t think it’ll be too much trouble.”

I’ve never pressed Gertrude on why she and Harry only had one child. I have my theories, one of which she has alluded to: one child was enough. Neither Gertrude nor Harry, despite the pressure of their environs, longed for more. She was twenty-three when Aidan was born and could be presiding over a teeming household by now, four or five at least barreling through, a brood not far off from what the Muellers have brought forth. Three is enough for me and plenty for Daniella; we’re satisfied. I’m always surprised Harry, so in need of a descendant to care for the homestead, didn’t demand more. What passes between them is still unclear to me, even with the time I’ve spent with her, turning over her relationship. If they were a city couple, I wouldn’t wonder much at all.

Apartments are filled enough with childless couples, let alone three children stomping through, and no one can feasibly afford an apartment with four bedrooms unless it shows up in an area that has just suffered a dire fiscal crisis or seismic crime spike. A house like this is hungry; it aches to be filled. Right now, we’ll do.

I bend down and inspect. There’s hardly a leak at all. Well, of course. And how many tools are actually in my tool kit? I grin to myself, in the semi-dark around the piping, and slowly rise. I’m six-one or six-two depending on the day and who is measuring, and Gertrude comes just up to my chin. The leather pouch rests at my foot. There’s an interior weight to this house I’ve always liked, of lives lived and fortunes sought, and I spy an oversized metallic wall clock against the kitchen’s far wall, ticking away softly. It’s nearly a quarter to four.

“No trouble,” I say. “Water is hardly dripping at all.”

Longer ago, I could savor the anticipation, the silence heavy between us before fast action. Gertrude’s face is warm yet impregnable, like a poster board for a vanished icon only I can recall, and I glance downward, toward her flexing calves and shoe tops.

Daniella has a white pair of Adidas she wears for walks that are not so different than these.

“Good, Teddy.”

I forgo whatever ceremony is left—the lingering gaze, the breathy intake, the heartbeat at a nice hop—and kiss her on the lips, harder than I intended. I always enjoy this taste. If I haven’t been chewing gum, she has, and I catch the aftertaste of something cool, Eclipse or Extra, and let it settle on my own tongue.

Her eyes are closed, as usual, and I kiss her again, biting her lower lip, feeling the light, delicious click of her incisors.

“Upstairs,” she says.

I watch her on the banister, careful, and we go to one of the guest bedrooms. My favorite, where we typically end up, has the best view of the verdant farmland, two lace curtains parted for miles of surging corn. The sheets are an off-white, cottony, and the mattress has a good spring to it because so few (other than us) sleep there. She hesitates slightly at the top of the stairs—a cramping in her calf? a second thought?—and veers left, thankfully, to our spot. I slide after her like a furtive child, my toes soft on the hardwood, and I’m mouse quiet behind her. There’s no reason to be, really. Only Aidan is a threat to return and Aidan has better places to be on a Sunday afternoon. If he returns at all, it’ll be at sunset, when Gertrude will start calling him on the cell phone Harry bought for him last year.

“I’m glad we’re here,” I tell her as she undresses and I’m unbuttoning my trousers.

“This house?”

“This room.”

“Oh, I hate it.”

“I love it. Look at the view.”

“You can only look at it so many times.”

“You want a view of town.”

“I don’t want that either.”

“A straight shot to the Pine Haven College clocktower, the sprawling quad, coeds with Shakespeare tucked under their arms.”

“The college is hell-bound.”

“Not all of it.”

“Oh, Pastor Starr has done a survey, examined every last soul.”

She’s drawn the curtains and soon I’m on top of her. Usually, she wants to rush under the sheets, but not today. We haven’t even shut the door.

“Realistically, in a school of fourteen hundred undergraduates, there are a few who’ve accepted Jesus Christ as their Lord and savior.”

“If they said it, they’re lying.”

“Don’t underestimate the human heart, Gertrude.”

I take my own survey of her naked body. I hope, in those distant eyes, she’s doing the same of mine.

We slide under the covers after we’re done. I have my hand on her breast and she’s noodling with my chest hair. It was one of our best yet, and I’m trying to recall, almost desperately, how many times we have been together. Suddenly, this catalog matters. If a memory can’t be summoned, did the experience ever produce it?

This is why, perhaps, we need God. God is always watching and God can remember for us.

“I meant it about the college,” Gertrude says.

“We can pull up stakes and move Trinity then. Maybe the Breckenridge homestead will have us.”

“I’d like that. Harry would finally get that heart attack he’s threatening to have.”

“Pine Haven College was founded by Presbyterians. At some point, they gave up.”

“I don’t like Presbyterians, but I wish they stuck with it. I can’t go in there every day and listen to these people.”

“These people? The students? The coworkers?”

“All of the above. They’re a hive. They want to rewrite history, rewrite the human body.”

“It’s the fad of the moment, but I think it’s giving way. The social justice enthusiasms.”

“They are all filled with hatred. No one hates more than a Democrat at a liberal arts college. No one burns more. No one aches for more blood.”

“They believe they have clarity, even if their vision is confused. That can be a dangerous thing.”

She sits up slightly, her hazel eyes flitting in my direction.

Whatever I’ve said, it’s not good enough.

“You speak about it with such detachment.”

“Not at all. I’m only saying, they’re confused. A liberal mind builds a church without God. A church of deconstruction, a church of, well, academia. It’s a confused church, since it lacks a center.”

“I need to get out of there. But then I’m here. I’m on this farm. Do you know something, Teddy—what I think about sometimes?”

I’m still in a state of postcoital placidity, my eyelids slightly drooped, my groin tingling faintly. I could fall out for a few hours, doze until nightfall, though curling up here is simply not an option. Daniella will set dinner by seven, Theodore will be home, Chloe will be asking for Daddy, and little Austin may want to be held. Images of the very near-future rush through me and it’s hard to focus on what Gertrude is saying. I want to give over myself fully, as I might at Trinity, particularly when she raises a thorny theological matter. Gertrude is a close, close reader, and I appreciate her surgical precision in all matters of life. But here and now, I’m not sure I want her to tell me so much about herself—about the homestead, the college, Harry. I understand it well enough. It’s all weight on her she’d rather shed.

“What do you think about?”

“How it would be great if it all burned down.”

It’s advice I should give and it’s advice I don’t necessarily have. Not now, anyway, not in this state. I can rack my brain for a Bible passage but I know that’s not what Gertrude requires from me. She wants wisdom from a friend, a lover, even a therapist, and I can only be all three for so long. I counsel several couples at Trinity (not Harry and Gertrude) and their difficulties, which are common in long marriages, are not quite so charged, so rage-flecked. Their unions have a sort of irritable ease that is salved by more communication, empathy, and prayer. CEP (hard C), I call it privately, and I can offer a dosage a week and stroll out of there arm in arm with man and woman if I so choose.

Gertrude does not want, I assume, to communicate with Harry. She does not want to empathize with him. She will pray alone, undertaking her own winding and very private conversation with God. This is the first time she has told me she wants to burn down the homestead.

“You shouldn’t burn down the homestead.”

“Who said I will? I never will. It’s a wish for an act. I don’t want Aidan or Harry to be home.”

“When does Aidan get home?”

“You’ll be long gone by then, don’t panic. I know that’s your worry, Teddy. You didn’t bargain for this. It’s like when your real estate clients want to talk God. If it bothers you so much, you should get two cell phones.”

“It doesn’t bother me at all. I welcome such talk. You can tell me anything. I understand you and Harry are in a rough patch. It can be hard, at times, to get along. Have you told him how you feel?”

A ludicrous suggestion, and I know it the instant it leaves my mouth and hangs between us. I’ve been lured into an exchange I’ll have to abort soon. Typically, Gertrude is not this way, her resentments toward Harry buried stomach-deep, out of view.

The hospital stay, if anything, was supposed to short-circuit such chatter completely and give us more running room in our time together. He’ll be at Luce Memorial at least another week, from what I understand. Beyond that, Harry is a problem I cannot solve.

I won’t recommend divorce. It’s not as if a sizable minority of the congregation hasn’t been divorced already or is living together unmarried—and I’m not such an obstinate goat that I wouldn’t advise separation, under such and such circumstances—but I won’t be in the business of actively encouraging disunion, even if it adds to the cleansing side of the ledger. Aidan, deluded as he might be, deserves a married father and mother. This homestead won’t be haunted by Harry alone—Gertrude would have to leave, and that’s clearly what Gertrude wants—and it won’t be my responsibility when that balky scenario inevitably devolves, an unmoored single father barely tending to the corn as the child spins off into nefarious orbits.

“I tell him all the time. I tell him every week.”

“Direct.”

“He’s somewhat like you. He’s comfortable in abstractions.”

“Maybe that’s why I’m here. You can tell him something twelve consecutive times and he won’t believe you because it hasn’t yet settled into the makeup of his universe. It’s neither right nor wrong—it just doesn’t exist.”

“At some point, it will exist. You just have to wait for it. You have to wait for it to settle. He’s that species of livestock.”

“I don’t have that kind of time.”

True enough. God can call us up whenever he decides; He is the only timekeeper of relevance here. No one has a kind of time. They have a ceaseless ticking forward, sometimes deadening, sometimes sprightly, and you hope to sniff out the worthwhile moments in between. Mostly, I hope, those are at Trinity. I do believe most of the congregation, even Gertrude, views it as a peak of the week. When I preach, I want them all to feel relevant.

They are the hum, the news, what the worthy talk about. They are onstage. God is watching and they must be celebrated. True worshippers know they are being watched and they cherish this knowledge, hugging it close like they would their own children.

Gertrude has stood up and I follow the unsunned undersides of her thighs as she hunts for her discarded clothing. I should do the same. At the foot of the bed are my trousers, my leather belt still hooked in, and somewhere down below my argyles.

My unbuttoned dress shirt, an understated clamshell white from Ralph Lauren, has fallen down too, and I mimic a blind man as I reach for it on the floor. There’s no good way to depart, really—certainly not from here.

“Remember,” I say, when I’ve got my shirt buttoned and my pants up, “the people of the college can’t change you.”

“And I can’t change them.”

“Their time will come.”

I say this, nearly believing it, and decide now is a good enough time to get home to my wife and children.

Excited for this book!

Love the note about how dirty Teddy’s Chevy gets, like it’s paying attention to the muddy behaviour of its driver. But a weekly cleaning at Chip’s Wash! A baptism washes away the week’s sins, right?