The Anxious Liberal

Considering one end of neoliberalism

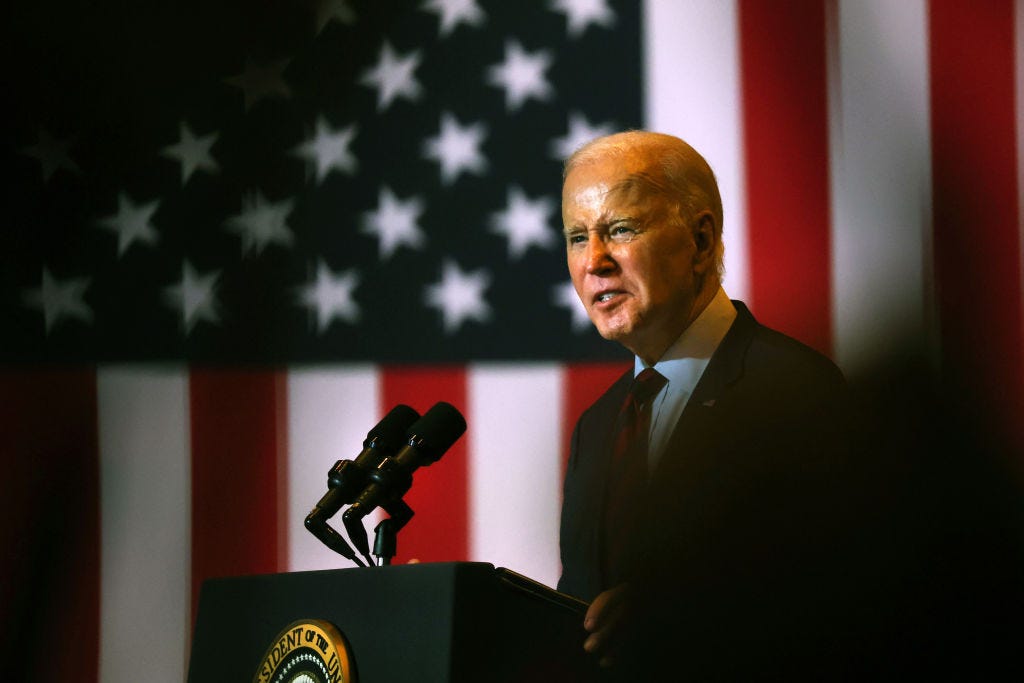

These should be sweet enough times for the educated, higher-status left-liberal. If his preferred candidate (Elizabeth Warren, Pete Buttigieg) didn’t claim the Democratic nomination, Joe Biden knocked out Donald Trump and restored the technocrats to government. The surviving periodicals of the print apocalypse (the New York Times, the Washington Post, the New Yorker, the Atlantic) all dutifully echo, whenever necessary, his proclivities and viewpoints, and the most muscular voices at CNN and MSNBC can all be counted on to affirm whatever it is he may be feeling most passionate about in the evening hours. If he cares enough about social media, there is a new white knight (Mark Zuckerberg’s Threads) on the scene, his powers restorative because they’re trained on a MAGA-shaded villain (Elon Musk, and his “X”). The resistance may lack some verve, halfway through 2023, but a third Trump indictment could do the trick of getting the old bands back together.

Yet it’s never so simple. The left-liberal, unlike the frothing right-winger, doesn’t feel the same sort of total victory, the same stirring and savage triumph. The Right can “own” libs; the Left has no equivalent posture. The left-liberal frets. At the conclusion of a recent essay about neoliberalism in the New Yorker—the author, Louis Menand, is decidedly not for it, though he’s wary, like all good left-liberals, of excesses of both the Left and the Right—arrives a lament for what Republicans, in the 2020s, have become. “Republicans eagerly lambaste Big Tech and clash with “woke” corporations, more intent on fighting a culture war than on championing commerce,” Menand writes. “People used to pray for the end of neoliberalism. Unfortunately, this is what it looks like.”

Essays like these are never so strident. I myself strive, like Menand, for a more meditative manner; you’ll know what I think, but I’m not going to bash you with my rhetorical mace in every single sentence. I want to lay the facts out, chew them over, come to an understanding—and then, at some point, strike hard. Menand, after taking us through a tour of Friedman and von Hayek and the history of New Deal backlash—and a worthy exploration of how conservatives misinterpret Adam Smith—brings us to the crux of it, his crux. Sometimes I wish essays like these would rumble on from here. “Unfortunately, this is what it looks like” is the very last sentence, and kneaded into it is a kind of unfulfilled promise. You know what I think now, but not all that much. Is it unfortunate, then, that neoliberalism is on the wane—particularly if it means Republicans want to fight a culture war and whine about “woke” instead of “championing commerce?” Yes, apparently. But why? In the final paragraph, Menand writes that both Democrats and Republicans have “drifted closer to something like mercantilism; the language of the markets has lost its magic.” Before his final strike against the Republicans, Menand notes that “Bidenomics” comes with “immense government spending” and contrasts it with the “new cadre” of “protectionists, crony capitalists, ethnonationalists, and social and cultural provincials” who are, in his view, “rewriting party platforms.” The implication is clear enough: Menand thinks there’s a limit to how much we should celebrate the apparent demise of neoliberalism. Look, he tells us, what it has wrought.

Has the movement away from market economics—the belief that reduced government spending, lower taxes, and the unchecked growth of the private sector could solve societal ills across the world—led to unintended consequences? Though Menand never carries the idea much further, he seems to long, at least somewhat, for the recent past he spent the last few thousand words critiquing. Remember when the Chamber of Commerce Republicans ran the show. Remember when Mitt Romney and Paul Ryan were the standard bearers of the GOP, and Ryan was fighting the good fight against Trump from his speakership perch. It is worse, in Menand’s formulation, that Republicans have departed from their primly neoliberalism for cultural fare. Can’t they leave Big Tech alone? Can’t they be kinder to Disney? The dark heart of the new Republicanism is its revanchism—its hatred of immigrants, its flirtation with white nationalists—and Menand notes this in his reference to the “ethnonationalists.” For that alone, there is much to despair over, as well as Trump’s disregard for America’s democratic institutions—not as fragile as the pundits would have you believe, but still vulnerable to a savvier strongman.

If you are not much of a materialist, you will nod solemnly along with Menand, who mostly speaks for the consensus at the New Yorker and the mastheads of the aforementioned newspapers and magazines. It was better, then, when Republicans cared chiefly about catering to large corporations, lowering the tax burden on the rich, and slashing public welfare programs. This was the essence of Ryan’s speakership; Trump’s only tangible legislative success came when Ryan’s House and Mitch McConnell’s Senate passed a large corporate tax cut in 2017. They could not, as Ryan and McConnell also hoped, repeal the Affordable Care Act, and it’s plausible that if a more competent Republican like Ted Cruz or Marco Rubio had been elected in 2016, the healthcare law could have been blown apart. Trump, as president, was a traditional conservative on the substance—the judicial appointments, the gutting of regulatory agencies like the EPA—who managed to confound liberal expectations of him in other ways. Trump was not a movement conservative, and he only won over the “commerce” types when he proved he would be friendly to the wealthiest taxpayers. Evangelicals joined him when he showed, through his choice of Supreme Court justices, he could be trusted to deliver on the destruction of Roe v. Wade.

Trump, however, reoriented the rhetorical direction of the Republican Party in a manner that economic leftists—the materialists—could appreciate more, at least sotto voce, than the left-liberals. Trump is well-known for deriding free-trade agreements like NAFTA, long the bane of labor unions, and championing protectionism. He attracts less attention for becoming the first prominent Republican in the modern era to explicitly campaign against gutting Social Security and Medicare. He has mocked Ron DeSantis, who began his career as a movement conservative in the House, for embracing safety net cuts. The liberal is right to retort that Trump is a liar and corrupt and can’t be taken seriously on any of these fronts. Soon, he’ll be indicted again. Republicans will never be, in this lifetime at least, Debsian economic populists. But the Tea Party fervor for government shrinkage has dissipated. Trump was the president who signed the CARES Act into law in the depths of the pandemic, authorizing billions of dollars in government spending that likely saved the United States from a second Great Depression. Would President Ted Cruz have rubberstamped legislation sent up by Nancy Pelosi’s Congress? Not likely. Trump’s dominance in the 2024 primary is proof less of what has catalyzed than what has disappeared: the lust for austerity. There are enough Chicago School Republicans still skittering about, but they no longer have the power to crush government. Even DeSantis, as governor of Florida, raised the pay of public school teachers.

Isn’t it better that Republicans care more about bullying Disney and Facebook than cutting the federal government in half? Many left-liberals bemoan the lack of trust Americans show in their government, but it’s not as if these voters don’t trust the feds to deliver a Social Security check or pay their disability or patch potholes. They are wary of experts, and with some good reason. The official narrative of Covid politics is that Republican and internet-driven misinformation fueled a bloodbath. To an extent, this is true—it would have been better if the elderly were more quickly and widely vaccinated and Republicans encouraged this instead of flocking to failed cures—but it elides how much the public health establishment confused and alienated the American public. Menand approvingly writes on The Big Myth, a new book by Naomi Oreskes and Erik Conway, which argues that 40 percent of America’s Covid deaths could have been prevented if Americans trusted “science, government, and one another.” Years of “science-bashing” and “anti-government messaging have taught Americans not to.” The essay proceeds elsewhere from there because many writers, generally, do not want to linger over the more uncomfortable aspects of the pandemic.

Consider the anti-populism of the sentiment. If only Americans trusted elites first— “one another” is, notably, the third item on the checklist—they would not have suffered so much. Maybe! It would have helped, though, if these elites weren’t so astonishingly inconsistent and audacious about masking their own failure. Perhaps, next time, they shouldn’t upend common-sense and tell millions of Americans not to wear masks at the onset of deadly airborne pandemic before eventually reversing course. Perhaps they should not furiously argue a new vaccine cannot possibly be delivered on a one-year timeline before declaring, yes, this unprecedented vaccine will work all kinds of wonders, like immediately ceasing the transmission of Covid and virtually guaranteeing you can never get the virus again. Perhaps they should not claim, against all available evidence, certain kinds of activities are safe enough during the deadly pandemic because they are simply more moral than other activities. Perhaps they should not underplay the cost of indefinitely shutting down public schools, playgrounds, and small businesses, or impose unprecedented mandates undergirded by plainly peculiar logic. Perhaps they should not actively lie about the debate over the origins of the virus. Perhaps, above all, it is not wise to make certain public health professionals into cult heroes when it’s entirely unclear, given the carnage across the country, why such praise is warranted. When they fail, technocrats tend to not blame themselves. There are the masses, frothing in their ignorance. So many people, and they all get a say. How nice it would be if they could shut up and listen to the experts. The liberal, in this strange new decade, might not be so anxious.

I am in particular agreement with your last paragraph, well-stated. Covid was even worse than the Iraq War as an episode of incompetent "expert" liars and their media allies showing us who they are. And Menand thinks we are insufficiently deferential? I loved the Metaphysical Club but I hate to think how obnoxious that book would be if he rewrote it now.

(Years of “science-bashing” and “anti-government messaging have taught Americans not to.”)

Actually, it's decades of being lied to by the ruling elites that has shown us that we are, in fact, being lied to.

WMD.

Iraq's involvement in 9/11.

Desperate attempts to crucify anyone who would suggest that the strange mutant COVID virus killing millions came from the lab modifying COVID in the town where the outbreak originated.

And these are just the lies (which strangely always seem to be incredibly profitable for the donor class!) that have resulted in hundreds of thousands of deaths.

Then there's the economic policies:

Offshoring is good, actually!

Monopolies are fine!

Cutting taxes will make everyone rich!

Corporate profits and concentration of wealth have caused record inflation! We'd better throw more poor people out of work, because reasons!

Then predatory vulture capitalists can buy up more housing stock! The middle class not being able to build equity is good, actually!

If the government wants to be trusted, perhaps they should stop being caught in obvious transparent lies.

And if people want the government to stop lying to them, they need to hold their own parties accountable first.