The Death of Debate Culture

On the Guernica implosion and what comes next

A version of this essay first appeared in Persuasion.

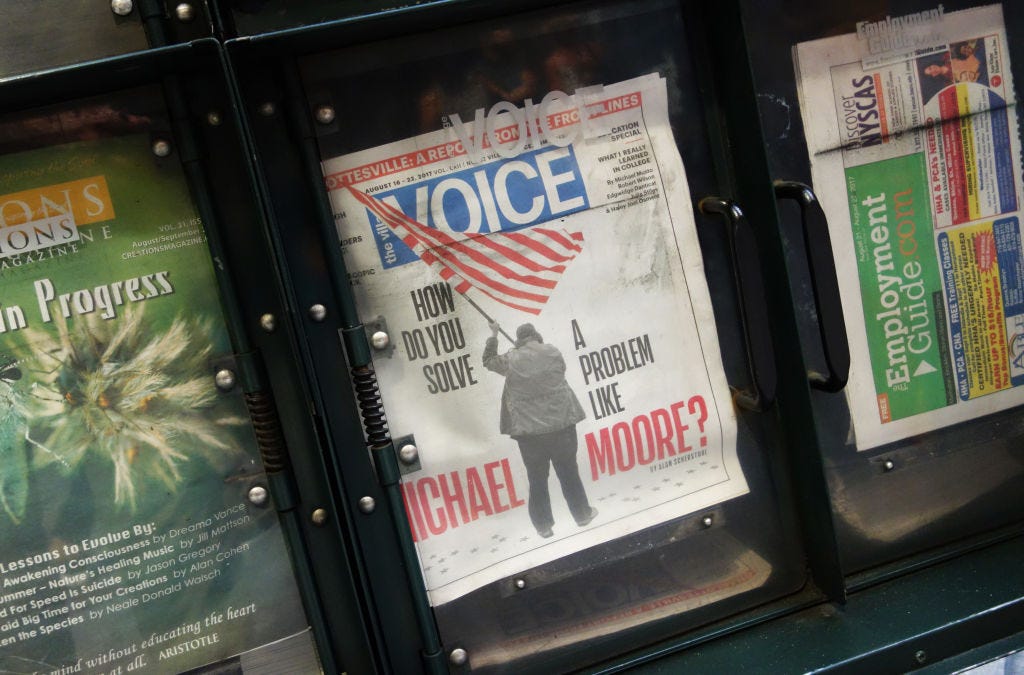

Not long ago, I finished Tricia Romano’s oral history of the Village Voice, which was once America’s premier alternative newspaper. Even if you don’t care much about the Voice, you’ll find yourself wading through a half century of fascinating, explosive history. One of the great early breaks of my career was getting to write for the Voice; by 2016, it was past its various heydays—every era of the Voice, from 1955 onward, has its voluble defenders—but it was still a vibrant weekly newspaper with talented staff and strong arts coverage. I had the fortune of working with top industry editors like Will Bourne and Joe Levy, and I felt, for the first time, the freedom to write fluidly and aggressively about what I wanted. It was at the Voice where I found something of the tone you’ll encounter here at this Substack. I was paid to report and make arguments and I enjoyed it all tremendously. Writing critically on City Hall and Albany, I discovered a local audience hungry for entertaining and adversarial political coverage.

The Voice was, through most of its prime existence, a liberal or left-wing newspaper, never as far-left as rivals like the East Village Other but far more radical than the New York Times. In our modern conception of what publications are, this should have meant a certain uniformity of political outlook or style. But the most remarkable reality of the old Voice—beyond the fact that Rupert Murdoch owned it for nearly a decade—was that its writers could absolutely go to war with each other. These weren’t water cooler fights; these were columns and letter sections filled with bilious criticism of pieces their own colleagues had written. The battles were as personal as they were ideological.

The reporter Howard Blum told Romano that the Voice was the internet before the internet and this is true in the sense that the Voice, at least in the 1950s and 1960s, rarely mediated or filtered its writers, allowing a platform that was not so different from Substack today. At times, reading many of the talented writers on Substack, I’ve longed for something like the Voice, one ur-news organization to wrangle all of these rising columnists and essayists. What can make certain Substacks great is what made the Voice, through all of the decades, so intriguing: unpredictability. The Voice published radical feminists. It published Nat Hentoff, a civil libertarian who was staunchly against abortion. It published Greg Tate, who wrote brilliantly on hip-hop, and Stanley Crouch, who wrote brilliantly on jazz and reviled hip-hop. It was the domain of outer borough white working class writers like Pete Hamill and Jack Newfield, and the domain of Jill Johnston, the famed lesbian feminist. Unknown writers could furiously denounce the Voice in the letters section and find themselves, shortly afterward, with their own columns. It was that kind of newspaper. There often wasn’t comity, yet it all kept chugging along.

I was reminded of the Voice legacy after around a dozen staff members resigned last month from Guernica, a well-regarded literary magazine. The staffers, who were volunteers, quit after Guernica published an essay by an Israeli writer grappling with Oct. 7 and her volunteer work driving Palestinian children from the West Bank to receive care at Israeli hospitals. Joanna Chen, a translator of Hebrew and Arabic poetry, wrote about trying to reconnect with a Palestinian friend and former colleague after the attacks, and of not knowing how to respond when her friend texted back reports of Israel blasting a hospital complex in Gaza. “Beyond terrible, I finally wrote, knowing our conversation was over,” she wrote in her essay. “I felt inexplicably ashamed, as if she were pointing a finger at me. I also felt stupid—this was war, and whether I liked it or not, Nuha and I were standing at opposite ends of the very bridge I hoped to cross. I had been naïve; this conflict was bigger than the both of us.”

Guernica’s staff revolted and resigned en masse. Guernica, in turn, deleted the essay from its website. April Zhu, who resigned as a senior editor, wrote that Chen’s essay refused to trace the shape of a “violent, imperialist, colonial power” and makes the “systematic and historic dehumanization of Palestinians...a non-issue.” Rather than rebut Chen with their own essays, the writers chose to leave Guernica; Guernica itself, rather than offer a forum for debate, erased the piece altogether. Better to pretend a certain kind of wrongthink never existed than to battle it out in the public square.

A strange, if inevitable, flattening has come with digital life. So many journals and publications sound alike—their politics indistinguishable, the writers circulating between them interchangeable. On Israel and Gaza, there are genuine divides borne out in American institutions that, when it comes to your typical online publication or journal, are not as evident. If a publication is outwardly conservative or Republican-aligned, it is no less a monoculture. Slavish devotion to Donald Trump (and the Israeli perspective) is de rigueur. Meaningful debate will not happen.

It would be easy—and correct—to diagnose the Guernica episode as a manifestation of the worst pathologies of 2010s-style social justice culture. Manichean thinking erases all nuance. Certain groups of people, safely ensconced in academic, corporate, or literary settings, proclaim themselves too threatened by the unfamiliar or objectionable to engage with it at all. They cocoon themselves, content to limit themselves intellectually in the name of safety.

On the left, the old Village Voice culture has faded. But the so-called anti-woke side can’t be said to be much better. Israel, again, is the instructive example. If anti-Zionists are guilty of rhetorical excess, arch-Zionists are prepared to match or even exceed them. In fact, it’s those who are most supportive of Israel who have adopted many of the same pathologies as the woke, treating debate and ideas themselves as mortal threats and defaulting, whenever possible, to their identity concerns. Standpoint epistemology dominates everywhere.

A Columbia University professor recently asked a student to remove a Palestine emoji from the end of their name online because it had “caused trauma reactions, making it difficult for some to remain present and not disassociate.” A London hospital was forced in early 2023 to take down artwork by Gaza schoolchildren after a pro-Israel organization complained that Jewish patients felt “vulnerable, harassed and victimised.” Israel hawks have infused just about every pro-Palestinian march in the U.S. with menace; an extremely popular gathering spot in New York City is supposedly off-limits because Jews (along with many other people) live nearby. The marches, it should be noted, are peaceful. The slogans though are beyond the pale.

People don’t shout at one another; they beseech the hall monitors above to ensure no one gets to shout at all. Guernica staffers cannot countenance someone who is not resolutely anti-Zionist. Israel hawks fight a holy war to get every pro-Palestine chapter purged from campus, every speaker banned, every bit of language placed off-limits. It all makes for the most suffocating of political climates. Long ago, in the heyday of print and the hothouse debate culture, the two sides could hash it out in newspapers, magazines, and debate panels, challenging each other, in the moment at least, to think critically. Those practices, absent some YouTube channels, podcasts, and Substacks, have gone out of fashion. (Preprogrammed pundit debates on CNN certainly don’t count.)

I am optimistic, though, that the climate will soon shift. The status quo can only be so stultifying for so long. If there will never be another Village Voice, there will be, at some point again, a return to straightforward engagement. The resignations and attempted cancellations will exhaust themselves. There’s only so much a culture will take.

It's funny -- I'm left but most of my readers are right-wing. I'm still breathing.

Insightful essay - well done!