The End of the Public Intellectual

Why Ta-Nehisi Coates won't change the paradigm on Israel and Palestine

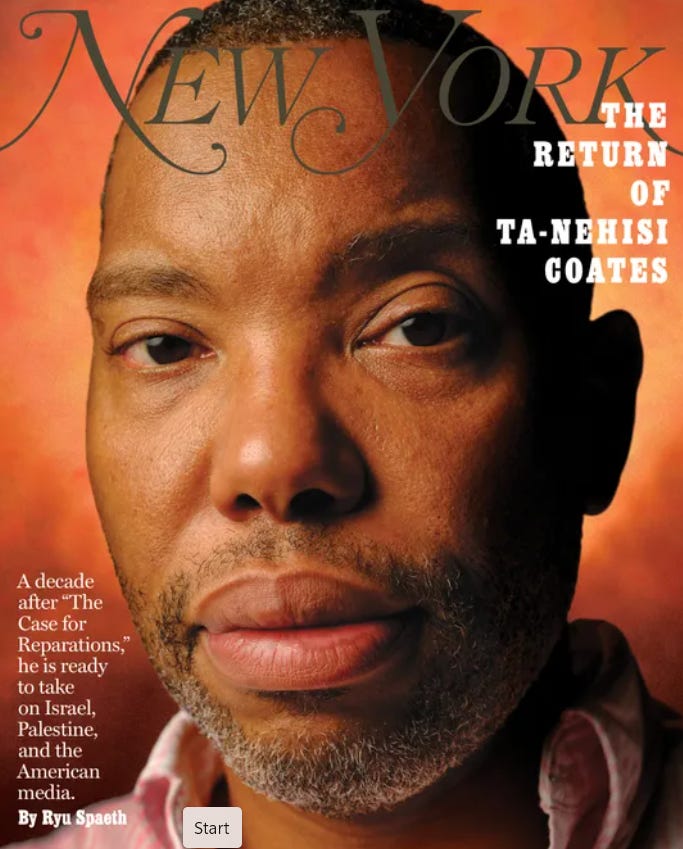

In August, the celebrated writer Ta-Nehisi Coates published a new column in Vanity Fair. It was his first piece for the magazine in four years, and his first anywhere in a very long time. In every sense, it marked his return: his fourth nonfiction book, The Message, has arrived, and the media establishment that Coates is both wary of but unquestionably belongs to is ready to make him a star again. Coates was the subject of a flattering cover profile in New York Magazine, one of the last glossies with tangible clout. Not long after, he found the national spotlight again after Tony Dokoupil, a CBS anchor, furiously questioned him over his lack of allegiance to Zionism during a TV appearance promoting The Message. Coates held his ground, insisting the violence and forced segregation the Palestinians endure in the occupied territories is immoral. Dokoupil sounded like he was running Miriam Adelson’s press shop. In a surprise move, CBS executives rebuked Dokoupil.

The thrust of the New York cover story is that Coates, so focused on issues of racial justice and anti-Black racism, is now ready to turn his full attention to the plight of the Palestinians under Israeli occupation. Just as he popularized concepts like structural racism and assumed, for a period, the perch James Baldwin once enjoyed in the national discourse, Coates could now speak the truth on Israel and Palestine and show his country the horrors that Zionism has wrought. He likens, in his writings and pronouncements, the treatment of Palestinians in the West Bank to how Blacks were punished under Jim Crow.

What intrigued me most was not that Coates was reemerging after several years outside the nonfiction spotlight—he wrote comics, published a novel, and took up screenwriting after leaving The Atlantic—but that his return, despite a publication in Vanity Fair and a full New York cover, just does not seem to matter all that much. Coates’ Vanity Fair column appeared during the Democratic National Convention, when I too was in Chicago, and I mentioned to several people that Coates was back. None, actually, seemed to know. And few offered much of a reaction. This was not, it seemed, the media equivalent of Michael Jordan returning to the Chicago Bulls.

Coates’ reach, at a certain point in the middle of the 2010s, was vast. Between the World and Me was not just a best-seller but a cultural touchstone for the social justice era. Coates’ elegant and oracular pessimism—his argument for reparations, and his inherent belief that racism remained deep in the fabric of the United States—was a direct rejoinder to Barack Obama’s promise of a post-racial future. It was also one Obama and his many acolytes were eager to engage with and even, at certain moments, celebrate. The college-educated progressive found much to revere in Coates. His Atlantic essays and books defined the pre-Trump age. He was famous, and virtually everything he published could make news or at least power a long social media cycle at the height of Old Twitter.

The premise of the reporting on Coates’ reemergence is that he will do for Palestine as he once did for Black Lives Matter and social justice, elevating a movement and making a certain kind of powerful and affluent liberal deeply uncomfortable. With discomfort, perhaps, will come institutional change. “I knew it was wrong from day one,” Coates told New York, referring to the occupation of the West Bank. “Day one — you know what I mean?”

This may be true. But Coates is probably not going to achieve the paradigm shift he seeks. The era of the public intellectual is coming to a close.