The Institution of Memory

More thoughts on the end

My father, who died almost a month ago, taught me many things. If there were obvious disadvantages to having an older father, this was clearly what I would gain: someone who had lived a long time and could pass along both wisdom and bare fact. My father was a very smart man who read widely. But there are many smart parents who read widely who don’t have children at fifty; age alone doesn’t bestow intellectual curiosity.

What my father possessed was memory. The 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s weren’t a textbook to him. In the case of the 50s and 60s, they didn’t represent a gauzy early childhood, memories half-formed but the stuff of full-fledged teendom and young adulthood. He wasn’t nine when JFK was killed; he was twenty-four, the same exact age as the president’s assassin. He was twenty-seven for the Summer of Love, in which he did not participate, and twenty-eight for the assassinations of RFK and MLK. He was, as his contemporary Ken Kesey once described himself, too young to be a beatnik and too old to be a hippie. He and I would agree that he arrived right on time.

We talked, naturally, about serious and non-serious things. The most non-serious, by far, was professional sports, baseball chiefly. My father passed his baseball fanaticism to me. And he passed, more importantly than that, his memories. Of the two of us, I was the one who cared more about baseball history. I’ve been perpetually interested in the eras I never lived through. In time, I knew more about 20s and 30s baseball than my father—the exploits of long-forgotten stars like Chuck Klein, Lefty Grove, Kiki Cuyler, and Arky Vaughan, a high school classmate of Richard Nixon—and he, in turn, could educate me on what was, for him, not history at all. I was, from a young age, the strange child who could recite starting lineups of baseball teams that played in the late 1940s and 1950s, when my father cared most intensely about the outcomes of the games.

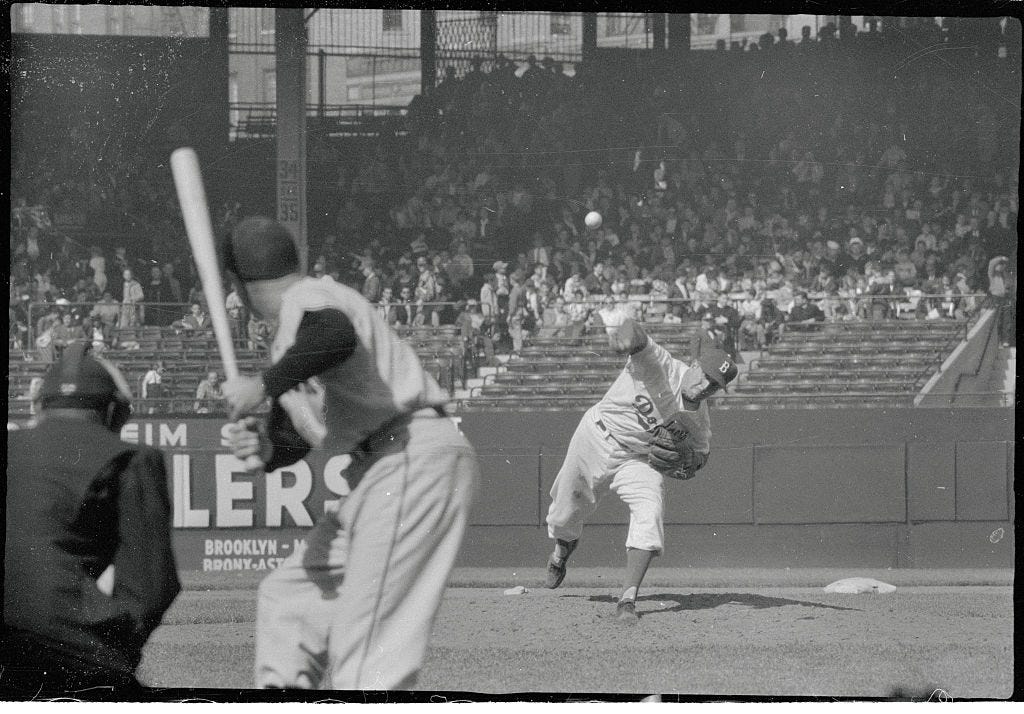

He grew up when New York had three professional baseball teams, all scattered to different boroughs. The Yankees, just like today, played in the Bronx. The Giants, his team, played at the Polo Grounds in upper Manhattan, a short walk across the Harlem River from Yankee Stadium. The Dodgers played in Brooklyn at Ebbets Field, several minutes from where my mother grew up. Today, they would call the neighborhood Prospect-Lefferts Gardens; back then, it was all Flatbush, and this was why the Dodgers’ star center fielder, Duke Snider, was the Duke of Flatbush.

From 1949 through 1958, a New York team appeared in the World Series every single year. Most of these were won by the Yankees. The Dodgers, very famously, won their lone Brooklyn title in 1955, sending the borough into a delirium. The Dodgers were the Boys of Summer, the team that integrated baseball with Jackie Robinson and brought along other Black stars like Roy Campanella and Don Newcombe. The Yankees were the Yankees, of DiMaggio and then Mantle, a juggernaut that, at one point, won five consecutive World Series. Since sporting life in America boiled down to baseball, boxing, horse-racing, and some college football, and baseball was plainly the most popular of the four, New York operated at the very center of the universe. Consider that Major League Baseball was not played west of St. Louis and a far greater percentage of the population was concentrated in New York—in the 1956 presidential election, New York boasted 45 electoral votes, more than any other state, including California—and you begin to understand what New York baseball meant then. The imagination of New York was the imagination of a nation. New York City was the American city-state.

My father rooted for the third team. Consider, too, how differently the fates of the Dodgers and Giants were regarded. The Dodgers’ decision to move to Los Angeles after the 1957 season was bemoaned for the rest of the century. Brooklyn Dodger nostalgia has subsumed multiple generations; the blue and white cap can still be found in stores today. Ask Bernie Sanders, Brooklyn-born in 1941, about one of the most traumatic events of his childhood, and he will talk about the Dodgers leaving. Brooklynites traced their falling fortunes in the 1960s and 1970s to the Dodgers heading west. It was allegedly emblematic of white flight, the surge in crime, the crumbling of a certain wholesome ethos. Far removed from this time, I can view the Dodger departure differently. It was logical and good for baseball that the Dodgers went to Los Angeles. A booming West Coast city needed a team and baseball was only going to succeed if an established franchise came there right away, not an expansion crew of no-names. In 1959, the Los Angeles Dodgers won the World Series and soon it was the Brooklyn-born Sandy Koufax lifting them to two more titles in 1963 and 1965. LA fell in love, baseball grew richer, and New York eventually got its new National League franchise—my father’s new favorite—the Mets.

But the Giants! My father, years later, would remark with some amusement that few really cared. The Giants left Manhattan the same year the Dodgers left Brooklyn. They headed to San Francisco, where they, too, inaugurated a venerable new chapter for a franchise that remains popular to this day. The Giants and Dodgers simply transposed their fierce New York rivalry west. Throughout the 1960s, they would battle for the National League pennant, with Willie Mays, Willie McCovey, and Juan Marichal going up against Koufax, Don Drysdale, and Tommy Davis, another young star who got his start in the Brooklyn public schools. My father liked underdogs. He was drawn to the Giants because so many of his friends were Yankee and Dodger obsessives. He liked Mays, of course, and the overlooked left-handed ace from upstate New York, Johnny Antonelli. He lamented, like many, that Monte Irvin, a Black superstar who came out of the Negro Leagues, was not allowed to spend his prime years in the majors. He told me, too, about the obscurities. A left-hander who never grew anywhere close to six feet—the joke was, if he hadn’t drank the Jersey water, he would’ve been tall and strapping—my father was drawn to the more diminutive players, especially if they were lefties. “Little” Bobby Shantz, a pitcher who won an MVP with the Philadelphia Athletics, just turned 98 the other day. At five-six, he would not have been scouted today. Ferris Fain, also of the Athletics (great name! I can hear my father bellowing), played first base at five-eleven and won two battle titles. He loved Snuffy Stirnweiss of the Yankees (a great name hero who won a batting title in a World War II-depleted American League) and Fenton Mole, a Yankee first baseman who had all of 30 plate appearances in 1949, his lone year in the big leagues. Of the Giants, his favorite was their first baseman, the dependable Whitey Lockman. Lockman, of course, batted left-handed.

If you read the first chapter of Don DeLillo’s Underworld, later published as a standalone novella, Pafko at the Wall, you can find glimpses of my father’s childhood. DeLillo, three years my father’s senior, grew up in the Bronx and undoubtedly took in many games at the Polo Grounds, which he renders in Boschian detail. The Giants, I think, fit my father’s sensibility. They were very good in his youth, usually competing for the pennant and winning it twice, but they had long fallen from the regal perch they enjoyed in the early twentieth century, before the emergence of Babe Ruth’s Yankees. The Giants, in their last New York decade, were identity-deprived. The Dodgers were the heroes of blue collar, multiracial Brooklyn, one of the only employers in an apartheid nation that was desperate to hire more Jews and Blacks—it was good for business, given the fan base. The Yankees were the Yankees, an indominable American institution, equally beloved and loathed. The Giants, in such a schema, struggled to fit, but they attracted kids like my father, those who wanted to defy the crowd. The Giants were no less committed to integration than the Dodgers but they were far less celebrated for it. (The Yankees had a rather odious record, bringing their first Black player, Elston Howard, to the majors eight years after Robinson broke the color line.) The literati, largely, would not swoon for the Giants or romanticize the oblong Polo Grounds, with its infinite centerfield and schoolyard foul lines, the Shot Heard ‘Round the World traveling less than three hundred feet. The Mets played in the Polo Grounds before Shea Stadium was built. My father went to watch them there. For him, there was no question, when the Giants left, that he would wait for New York’s next National League team. He was not going to care about baseball in San Francisco.

Grief is multi-layered and many-tiered; it arrives at odd hours, and its triggers are forever subtle. I can go days without being particularly sad. And then, the old black logic rears up; he’s not coming back. The other day, I flipped through the sports section of the Post, doing what he had done so many thousands of times, coming to the standings, the box scores, the statistics in agate. He treated the box scores like the Old Testament. Here was the truth: batting averages, surnames, the attendance. I want to tell him what I’d found, to remark on last night’s game, to pass along the news that one of his contemporaries, Brooks Robinson, had just died. He’d probably agree with me that the Times obituary was a bit flimsy. I wonder where he is and what he’s doing, if these are questions even worth asking. I keep busy like he kept busy. His life was a whirl, and he was proud of that. I whirl on too. I keep the names of the ballplayers with me.

Your dad's era is/were my eras. Still alive and hobbling.

I was never interested in sports to the point of following a team or remembering stats.

I did sell pogey bait at the wooden baseball stadium near Fresno State's Ratcliffe stadium around sometime in 1944. What sticks in my memories of those games was how the audience would demonstrate irritation to a ump's call. Seat cushions and beer bottles would rain on to the field.

I also watched inter service boxing matches at Ratcliffe. We would sneak in and walk right down to ringside. A memory of that was of a one punch fight.

We have one tiny connection to the SF Giants because the son of one of the syndicate owners owns the next door cabin to ours at Donner Lake.

You are lucky to have those great memories of your dad. Not me. Mom and dad divorced in 1940.

My dad went off during the war to construction jobs around the world. My older brother went off to Europe in the 8th Air Force.

Wonderful article, thank you. My dad, a Cincinnati native and lifelong Reds fan, passed away in July, 3 months shy of his 97th birthday. He used to regale me with stories of the 1940 World Series champion Reds, including a few years ago, when he casually rattled off the starting rotation and their respective uniform numbers. During my teenage years in the 1970’s, we had a rather fraught and contentious relationship (largely my doing) and one of our few “safe” topics was the venerable Big Red Machine. I was extremely fortunate to have him for as long as I did, but like you, there are moments when I want to share something and am hit with the gut punch realization of no longer being able to. Thank you again