The New Status Anxiety

Thoughts on the Substack discourse

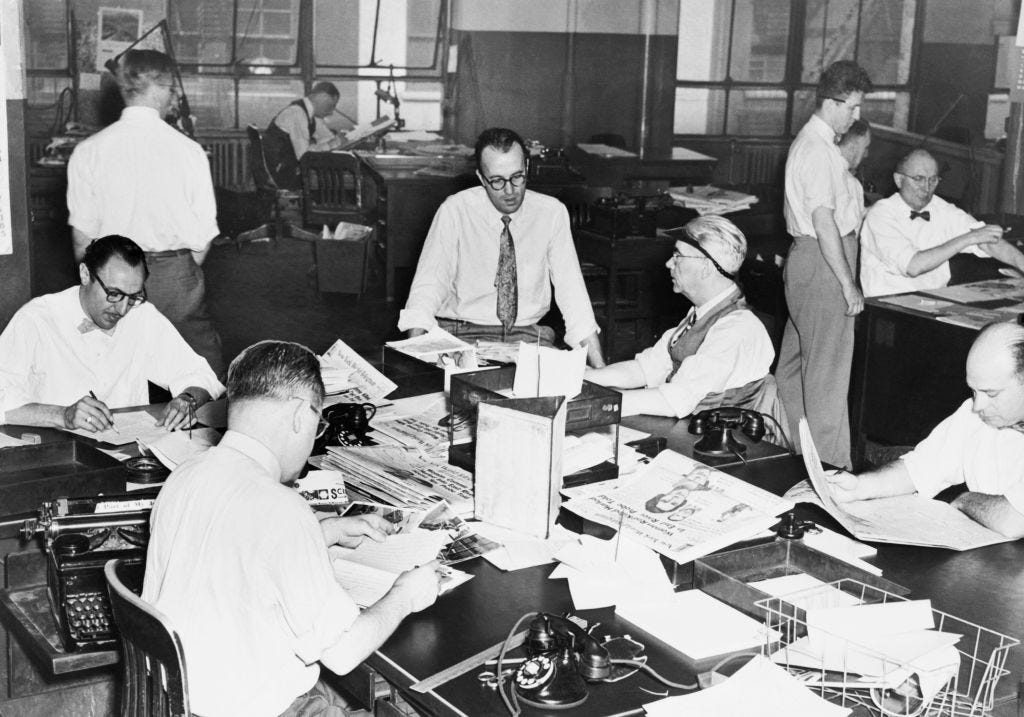

In the 2000s, there were many blogs. They were both popular and snickered at. Some of this was due to the name itself—nothing called a “blog” could carry much gravity—and some of it was a matter of money, or lack thereof. Most bloggers wrote for free. Some did manage successful websites that could generate ad revenue, but the business model was always tenuous. Few bloggers wanted to be bloggers forever. They dreamed of ascending to proper media organizations, where the cash and prestige were far greater. Most major bloggers of the era, like Ezra Klein, ended up with mainstream sinecures. Traditional journalists and columnists did not experience much status anxiety over the blogs. The blogs, rather, were a locus of curiosity, intrigue, and derision. A blogger, the old saw went, was someone writing in their mom’s basement. They could be intelligent, but they didn’t have a “real” job and the act of blogging showed they couldn’t hack it at the Washington Post or the New York Times. Put it this way: few believed blogs would supplant mainstream media, and they didn’t. For a while, media organizations either hired the top blogging talent or deputized some of their staff to do the equivalent of blogging. The late 2000s introduced the newspaper “live blog.” Ultimately, social media would bring the blogging era to a close. It was clear for those who valued the blogging discourse that Twitter, too fast-twitch and vapid, wouldn’t replicate that dynamic. Blogging wasn’t wonderful, but it could be substantive, and there was a free-range nature to the policy debates that would be lost in the 2010s.

Substack has brought back the best of the blogging age. The strongest writing on this platform, in fact, is far superior, since Substackers, unlike bloggers, don’t feel compelled to write in staccato bursts. There could be blog posts that were little more than brief sentences and links. Readers here expect more. Since Substack is, in essence, blogging software with a payment processor attached—their CMS remains more user-friendly than WordPress, and that partially explains the rapid growth—there are plenty of newsletters that aren’t very good. But that’s true of writing on the internet, broadly, and in the mainstream media. For every elegant essay or column in a prominent magazine, there is forgettable pap, and no shortage of prestige writing that will absolutely bore you. Substack cannot replace the collapsing newspapers and it’s not an answer to the crisis of trust in news. It is merely technology that has enabled writers to publish their work without the approval of institutions. The ideological and stylistic diversity on Substack is stunning, and it’s no exaggeration to say much of my favorite nonfiction writing is found here.

Yet follow the discourse enough, and you’ll find Substack, among a segment of the mainstream, continues to encounter withering criticism. The writer Sam Kahn answered much of it, and I don’t want to belabor his arguments too much other than to say I agree with them. I believe in the mainstream media—I write for various well-known publications and enjoy doing it—and I also believe Substack can exist as a necessary alternative, reinvigorating our writing culture. As someone who gladly operates in both spaces, I can say that both have tremendous value. There are logistical arguments to be made against Substack—the company itself still doesn’t turn a profit, and there are fears that, in the future, they may seek to extract greater revenue from paying subscribers or begin spamming us with advertisements—and those have merit. But most other arguments against Substack are utter nonsense. The platform’s founders have been right to not police anyone’s writing or introduce heavy-handed content moderation. Their Twitter competitor, Notes, has its drawbacks, but it’s largely helped me grow this newsletter’s audience, so I can’t complain. If anyone feels a kind of writing or posting is irking them, they can simply unsubscribe. I love my Substack experience because I subscribe to writers I enjoy reading. It’s not more complicated than that.

There’s a certain species of Substack critic that bothers me. This critic tends to be engaged with Substack in some manner; they write a newsletter or read frequently enough. They imply their efforts on Substack are not terribly serious or they note, with some frequency, Substack is inferior to the land of gatekeepers. There’s so much bad writing here! These people need editors! It’s a reaction not unlike that to the sprawling Vanity Fair story on Cormac McCarthy’s secret underage lover, Augusta Britt. Most of the venom was not reserved for the late McCarthy or Britt, now sixty-four, but for the twenty-something named Vincenzo Barney who wrote the piece. To spend any time on Twitter/X when that story was published was to encounter a bevy of journalists and pundits who were absolutely livid at Barney. They argued that he whitewashed grooming, even if Britt insisted she did not view herself as a victim. They mocked Barney’s purplish prose style. They mocked his name. They decried the thousands of dollars he was paid. I would not have written that Vanity Fair piece like Barney did, but Britt didn’t entrust me with her story and I didn’t spend a year reporting it, like Barney. If criticism of Barney, who is otherwise an unknown, may have been warranted—everyone, including me, warrants criticism—the question remains why it ended up so personalized. Not all of these critics seemed to be fighting for Britt’s honor or against the sexualized concept of a literary muse.

No, they very much wanted to bury Barney.

Barney, it so happens, snagged the literary scoop of the century because Britt herself left a comment on a Substack piece he wrote about Cormac McCarthy. They struck up a correspondence and became friends. It didn’t matter to Barney’s critics that the style of the Vanity Fair piece seemed to meet with Britt’s warm approval. Rather, they seemed offended that Barney wrote it at all. Why not a McCarthy scholar or a more seasoned journalist? Well, Britt wanted to tell her story to Barney, not them. A young writer with few major credits to his name wrote the most talked-about piece of literary journalism in many years. His Substack following wasn’t even that large. In the rancor over Barney’s reportage, there was obvious jealously. He wasn’t considered qualified enough for this kind of get. He had jumped the line.

The rage that built against Barney struck me as not so different than what has been boiling up against Substack. There are writers with deeper CVs or even jobs within the mainstream media who have found, on Substack, they aren’t as successful as they believe they should be. Their elite credentials cannot elevate them in the Substack discourse; relative unknowns outflank them, and don’t pay them much deference. Those who’ve found wider audiences on Substack are dismissed, in their minds, as panderers or grifters. The upstart Substack writers haven’t had to pitch their ideas to an editor or face down a raft of edits before publication. There’s been no participation in the editorial gatekeeping process that is supposed to dictate who has success and who does not. And for those in the mainstream who don’t have Substacks at all and view the whole enterprise skeptically, there is a growing anxiety that derives from the inability to pull rank. In the 2000s, it was easy to dismiss the blogger, even if he or she was popular. The mainstream media stood on firmer footing and trust in institutions was much greater. A blogger would always, spiritually at least, belong to the junior varsity. Substack, with its 30 million-odd subscribers across the platform and growing number of writers with followings in the thousands and tens of thousands, cannot be handwaved away any longer. Each year, it gets bigger. This bigness is its own kind of threat.

The median Substack writer is taken more seriously than the median 2000s blogger. There are no quips about Substackers living in mom’s basement. A few of them are millionaires, and many more are at least drawing some income from their newsletters. And if they’re not taking any income at all—if they write for free—they still have more social standing than the blogger, circa 2005. Substackers, unlike bloggers, aren’t necessarily yearning for mainstream approval. It would be nice—as would certain kinds of job offers—but the major media organizations, barring a few, are less robust than they were two decades ago. Blogging always carried with it the faint whiff of embarrassment. That is all fading now, as is the stigma around self-publishing. As trust in centralized institutions continues to crumble, a new paradigm emerges: individuals cultivating trust with their own audiences. This is not a system I celebrate or decry; it’s cut and dry reality, and no longer arguable. If you are a writer who wants to make some kind of connection with an audience in the 2020s, best to get on Substack. Few media organizations can do for you what an email list can.

Institutions still have tangible value. Substack hasn’t been able to replace the investigative reporting and travel journalism that well-funded newspapers used to regularly perform. A Substack writer might miss out on mentorship opportunities that come with working in a newsroom. There is an editor-writer relationship that, for young writers especially, is important to learn from. Much of me misses the old world. But my nostalgia won’t cloud my excitement for what’s in front of me: original, unpredictable voices filling my inbox every day. As a novelist, I pay particular attention to literary culture, and I can say with certainty that the writing and arguments happening around books now on Substack are of a depth and vigor that I have not seen in any establishment literary magazine or journal. I read them, and I read Substack. And it’s the Substack writers who are innovating. My prediction is that we are in the final wave of Substack opprobrium. Soon, it will all seem too inevitable and too central to the writing world writ large. The status anxiety will happily dissolve.

Solid piece Ross. I find the criticism also to be mostly jealousy, and mostly coming from those whose credentials haven’t somehow elevated them above the proletariat.

I like much of the writing I find on Substack (a fair amount recommended by you). My main criticism of Substack is how it's a sea of thousands of individual authors, when what I want is for writers to "Build Big Things." So I subscribe to a few Substack writers, but I'm more inclined to subscribe to a collective project. A few dollars a month to The Lever News, for instance, gets me top notch reporting and excellent ad-free podcasts. It's the same with Jacobin, with 75,000 print subscribers and some wonderful podcasts and a website viewed by millions each month. I even send Ralph Nader's Capital Hill Citizen $5 when they have a new issue (the only way to get it). A few days later a unique and substantial newspaper arrives in a brown envelope, highly recommended. I know that with Substack, the reader is supposed to build their own custom news source, but the process is alienating.

I would like Substack to experiment with allowing editors to easily create collective projects, like magazines, or Jacobin or Lever style websites. A reader could subscribe to the project, and would be able to read all the writing published within. Writers would likely get much less money per reader, but potentially they might get more readers, and they could still have their independent Substack feeds. The world needs more editing!