The New Subversives and the Fall of Colbert

On the emerging culture

On July 29, my new nonfiction book, Fascism or Genocide, will be released. Pre-order it now and get it delivered when it’s out! I’ll be having an event to celebrate. Stay tuned for more details.

And please buy Glass Century too, my new novel, which the Wall Street Journal said is charged with “heart-in-throat suspense” and Jewish Book World declared is a novel that “earns its place in the canon of the New York City novel, along with Don Delillo’s Underworld, Tom Wolfe’s The Bonfire of the Vanities, E. L. Doctorow’s Ragtime, and many others.”

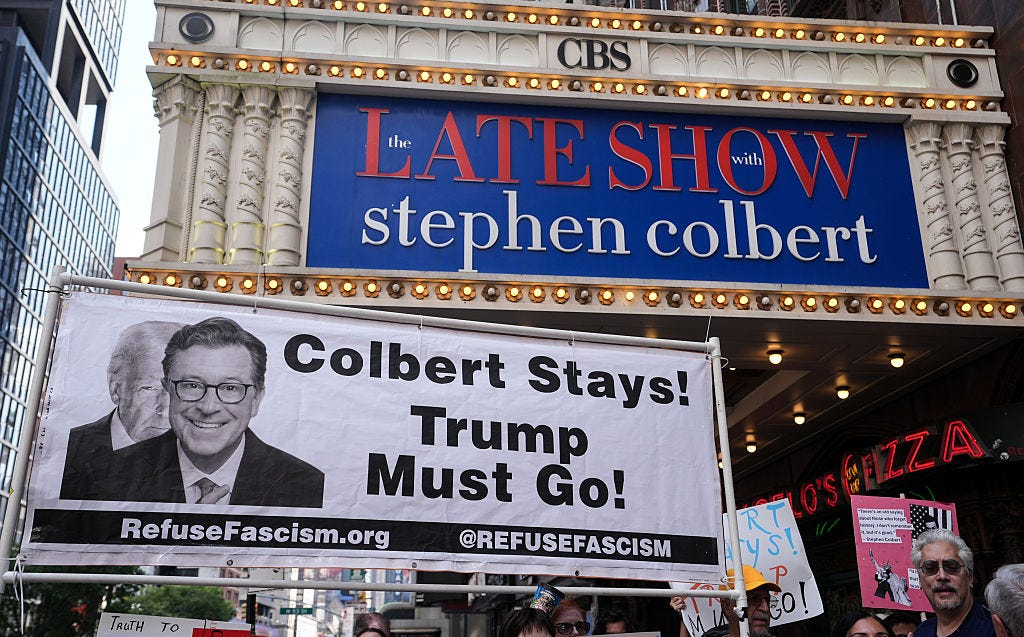

Like a ghostly flickering between radio stations on a country night—multiple voices, and realities, briefly converging on one dial—we witnessed, not long ago, the tangling of several Paramount-related narratives. One was the cancellation of The Late Show with Stephen Colbert, which many liberals interpreted as a sign that the corporate giant was attempting to appease Donald Trump ahead of a proposed merger with Skydance. This was, to some on the left, evidence that the president was imposing his will on the culture, as all good autocrats do. The second burst of news, coming shortly after the eventual Colbert cancellation—the comedian will remain on the air until next year—was that Paramount paid $1.25 billion for the rights to South Park, a comedy mainstay since the 1990s. Earlier in the month, in what was a disturbing development for First Amendment rights, Paramount forked over $16 million to settle Trump’s lawsuit over the editing of an interview on 60 Minutes. Paramount, as part of the settlement, will also release written transcripts of future 60 minutes interviews with presidential candidates.

The settlement has been rightly decried, and Paramount rightly lampooned, even on South Park. They are, like many corporate behemoths today, cowardly and cash-hungry. And it’s easy enough to see how they bowed to a bullying president, perhaps laying the groundwork for further capitulation in the future. But the Colbert story is not so straightforward; it is, as Nate Silver has argued, a blend of various factors, including the show’s bloated budget and falling ratings. The Late Show was losing money, and Paramount may have viewed a cancellation as both inevitable and a simple way to curry favor with the White House while protecting their bottom line. Notably, Paramount has not shown any buyer’s remorse over South Park, despite the show’s recent episode portraying Donald Trump as a venal nitwit in a sexual relationship with Satan. In fact, South Park’s strike against Trump is a likely boon for Paramount, since it’s the first time in many years a critical mass of ordinary people has felt the need to publicly react to a new South Park episode. Once at the vanguard, like The Simpsons, of the popular culture, South Park has become a legacy act in the last decade, entertaining a core fan base but not breaking through in any broader way. Some of this is less a function of the show’s quality than how mainstream culture has fractured so dramatically, with the collapse of cable television and rise of streaming herding most Americans into their own entertainment enclaves. When I was a teenager, I religiously watched new episodes of South Park on television every Wednesday night. On Thursday, at school, it wasn’t uncommon to hear dozens of boys quoting from the episode by lunchtime. Into college, I’d still huddle with friends over a television set to find out what Stan, Kyle, Cartman, and Kenny were up to on a given weeknight. This was what we did: wait patiently for our comedy appointment, and indulge.

That world is gone. Yet it’s a testament to Trey Parker and Matt Stone, South Park’s creators and perpetual showrunners, that an episode, in 2025, can still slash through the static and provoke a furious response from the White House. It was a reminder of what made South Park indelible and also, at one time, launched Stephen Colbert to the entertainment stratosphere: subversion. I am not alone in missing the character Colbert once played on Jon Stewart’s version of The Daily Show, and then his own Comedy Central half hour: the Bill O’Reillyesque blowhard who made a mockery of the dominant mode of right-wing communication in America. That Colbert was a stake in the heart of the Bush era, which is, by the standards of the 2020s, a genuine alternative universe. Trump is jingoistic, but he’s a ham, and even as he clamps down on the federal government, he is nowhere near as commanding as George W. Bush’s Republican Party in the aftermath of 9/11. This was the age of an unrelenting and unapologetic muscular patriotism. The anti-war left was deeply marginalized, to the point where careers could be derailed or ruined by any serious opposition to the neoconservative project. Michael Moore could oppose the Iraq War and get booed at the Oscars. The band then known as the Dixie Chicks, for public criticism of Bush in London, could face radio station blacklists and death threats. Bush himself, after the Twin Towers fell, boasted an approval rating of 90 percent, and he won re-election in 2004 despite the growing evidence that the invasion of Iraq was a catastrophe for both the United States and the Middle East. Into this environment stepped Stewart, whose cutting satire and streetwise liberalism was manna for the many disaffected Americans who wanted no part in Bush’s imperialism or the stultifying moralism of the rising Christian Right. Colbert, parodying Fox News—a network that, while only a decade old at that point, was already the cable TV juggernaut—was, in its own way, an act of comedic bravery because the Bush GOP was inordinately powerful and popular. His skewering of Bush, at the 2006 White House Correspondents’ Dinner, was, like all great comedy, a genuine risk.

His move to The Late Show, an understandable cash-out for an ambitious comic, never had much purpose. It is hard to find anyone under forty, in the 2020s, who watched Colbert on CBS regularly. This is not just a reflection of linear TV’s downfall; there weren’t many YouTube clips or social media hits passed around either. Colbert had morphed into a bland, self-satisfied liberal who seemed to sculpt jokes to comport with whatever might have been acceptable at a Democratic National Committee meeting. He was increasingly incurious and dull—his uncomfortable tussle with Stewart over Covid’s origins was one low point—and it’s disconcerting to watch the I Am America (And So Can You!) guy end up running a de facto infomercial for Pfizer. But it’s emblematic, too, of the mainstream culture’s plunge. In the twentieth and even early twenty-first centuries, the mainstream or macroculture was often in healthy tension with the subversion that bubbled below. Great, boundary-testing comedians were immensely popular, and elite tastemakers weren’t afraid of co-opting the counterculture to make their product all the better. Richard Pryor hosted a television show on NBC, and was able to sign with Warner Bros. Records. Andrew Dice Clay sold out Madison Square Garden. Joan Rivers and Sarah Silverman were leading television personalities. From the 1970s onward, it was difficult to call the major TV networks, record labels, and book publishers square—that is, until the last decade. Consider NBC’s Saturday Night Live, which had its last burst of tangible relevancy in the early Trump years when Kate McKinnon was brilliantly and ruthlessly mocking Hillary Clinton’s naked ambition and Alec Baldwin, through the power of his own brashness and egomania, was properly channeling Trump. SNL, today, putters on, but has no way of meeting the current political moment or even surprising viewers. Maya Rudolph, as Kamala Harris, always carried the whiff of too much reverence for her subject, and it’s difficult to fathom how a sketch comedy show that once downwardly defined Gerald Ford’s presidency was unable, at any point, to capture and or effectively lampoon Joe Biden’s evident senility.

The best and most groundbreaking comedy, unsurprisingly, is now found on the internet, through YouTube, Instagram, and TikTok. These microcultural entertainers, while growing and monetizing large followings, cannot find the same rewards as their underground predecessors because mainstream institutions are either too inept or too frail to properly absorb them. Online, the best Kamala Harris impersonator I found, without question, was a twentysomething comedian named Sienna Hubert-Ross who has several hundred thousand Instagram followers but no major network platform. The Harris of Hubert-Ross’ imagination bumbles like Chevy Chase’s Ford, and mercilessly exposes Harris’ awkwardness and plain political shortcomings. Whether Hubert-Ross is a Democrat or not is unknown to me; rather, her impersonation cuts far deeper at the heart of why Harris lost, and watching Hubert-Ross throughout the fall gave me the impression that Trump was probably rumbling to another term. Here is Hubert-Ross’ Harris straining to code-switch for a church audience. Here is Hubert-Ross’ Harris explaining, strangely, how she used to work at a McDonald’s. And here is Hubert-Ross’ Harris appearing on Call Her Daddy (“when I was a prosecutor, I put a lot of men in handcuffs”) or naming her dog Harriet Tubman or melting down, over white wine, on Election Night. An earlier version of SNL may have either tried to poach Hubert-Ross or crafted a parody that was infused with this kind of acidic, irreverent aesthetic. After Trump triumphed in 2016, the liberal comedy establishment appeared to fear that certain humor could either “punch down” or aid Trump who was, despite his preposterousness, suddenly outside the bounds of laughter. In the heat of 2024, SNL’s Harris had to be, to some extent, upstanding. She had to show respect for the real vice president. She was never going to be that funny.

Another intriguing, subversive digital star is Lionel McGloin, a twentysomething who hosts a YouTube show called No Cap on God. McGloin won a brief burst of mainstream attention when his edited video of the Democratic National Convention went viral, delighting conservatives who believed they had found their latest culture warrior. Thankfully, McGloin cannot be pigeonholed that easily; in the style of Sacha Baron Cohen, the former actor travels the country interviewing people on the street in the guise of various characters he has invented. At the DNC, McGloin plays a campy gay man, disarming Democratic delegates and politicians with questions like “can we please, this year—it’d be so brat—have a higher tax rate for rich white men?” But he’s equally mocking at a 2024 MAGA conference, asking young conservative women, as a red-tie-wearing (seemingly) straight conservative, if they’d ever date a liberal. (McGloin: “Would you rather date an illegal immigrant or a liberal?” MAGA girl: “Oh my gosh … um, that is, like, the worst question ever.”) His masterwork, which should find a wider audience soon, is a twenty-minute account of his trip to Israel. It’s better watched than explicated, and represents the platonic ideal of comedy: ridiculing, with tremendous panache, every single conceivable side of a political conflict. The Christian McGloin even includes a mock song about wanting to become Jewish. “God, I know you have choices but please, make me one of them!” McGloin sings, delightfully off-key. “Secret meetings, Nobel Prizes, high IQs—could it be possible if I was a Jeeeewww? Natalie Portman, Gal Gadot, learn your ways I will! My comment section will say you’re a Zionist shill!”

To spend enough time with the new subversives is to have little use for much of the comedy that major networks and even Hollywood, which has largely abandoned comedic films altogether, are producing these days. This is not worth celebrating, though. Mainstream institutions, if they are to survive, need women and men like Hubert-Ross and McGloin or, at the very minimum, what they represent. Their comedy doesn’t neatly occupy a red-blue axis, and allows for all kinds of sacred cows to come in for an easy drubbing. This was, of course, what made South Park so special in its heyday. Cultural critics would fiercely debate what political line South Park took most often or what, in their hearts, Parker and Stone believed. There was chatter about “South Park Republicans” and the allegedly libertarian bent of the show, but none of that ever quite made sense. Parker and Stone, like the great comedians of old, simply believed that there were no limits to a good joke. The pure merger of comedy and politics was always dangerous because the two arts—if politics can be called an art—serve diametrically opposed masters. Laughter is not contingent on the Democrats or Republicans winning in the fall. Humor doesn’t belong to a political regime. The Democrats protesting Colbert’s cancellation fail to acknowledge he is no longer funny. And the MAGA cohort delighting in a smug liberal’s downfall don’t quite comprehend how thick, predictable, and humorless they’ve become, passing along stale memes and sobbing whenever their Christ on Earth, Trump, endures a fresh bout of criticism. Trump himself is funny, but his most fervent and public followers are a garish and blundering lot, catastrophically lacking in his charisma and timing. Watch J.D. Vance try to tell a joke, and report back. The hope, then, is a comedy resurgence that is sufficiently inventive and free—and doesn’t bend the knee to any political power. It may very well come.

You said it, man. I'm so sick to death of everything being drafted into a red-vs-blue, left-vs-right culture war. Either everything is okay to lampoon, or nothing is.

Last year, I had a moment while watching "SNL" when I realized that I had warmer feelings towards Maya Rudolph's version of Kamala Harris than I did for the actual Harris, which was....weird. (That said, I do think James Austin Johnson's take on Donald Trump is pretty fantastic, in part because he nails the free-associative elements of Trump's speeches.)