The New York Times Ignores Its 20th Century Homophobia

What their Ed Koch feature missed

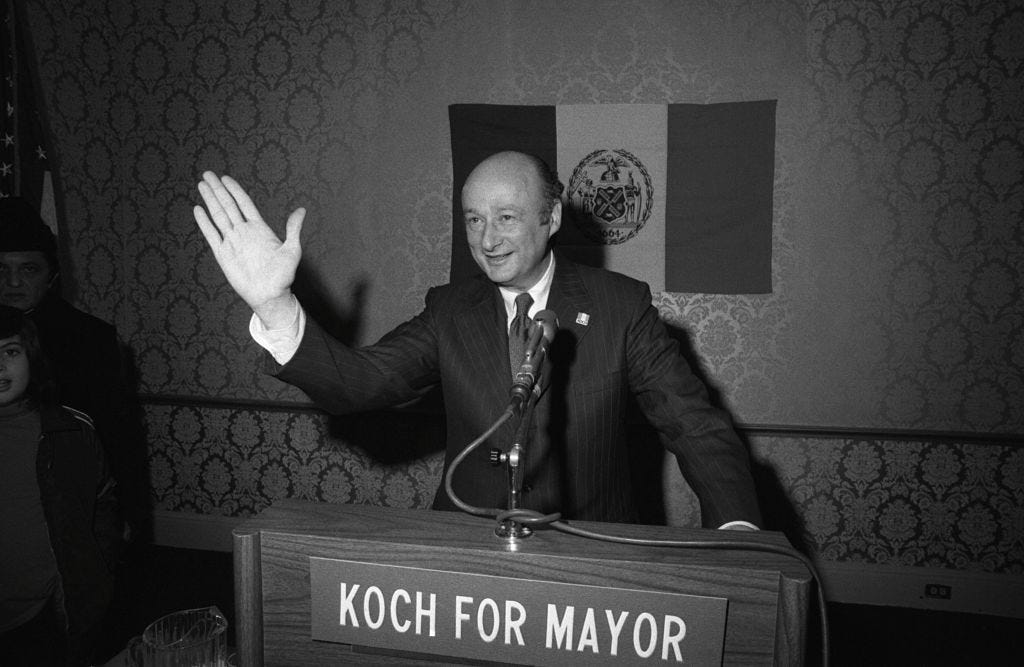

On Saturday, the New York Times published a 5,000-word investigation into the sexuality of New York’s 105th mayor, Ed Koch. Koch, who served from 1978 through 1989, was the city’s most iconic mayor in the second half the twentieth century, a brash and voluble Democrat who personified, like few others, the enormous and contradictory city he led. Koch rose to power at New York’s nadir, just three years after the largest city in America almost went bankrupt. In his era, he was one of the most famous politicians anywhere, and led an exceedingly public life right up until he died in 2013.

Koch zealously guarded his private life. He was a lifelong bachelor who insisted, until his death, he was heterosexual. Many people who worked in politics knew that he was a closeted gay man. Koch was deeply ambitious and believed his sexuality would be a political liability, even as the gay rights movement gained momentum in the 1960s and 1970s. The Times investigation is the first that confirms Koch’s sexuality, interviewing contemporaries who knew of a dating life he wanted kept secret. Ultimately, the Times investigation is newsworthy because Koch’s sexuality impacted the public stances he took. As the story meticulously notes. Koch was slow to react to the AIDS crisis, wary of overtly tackling a “gay” issue that, in his estimation, could lead political rivals to cast doubt on his public insistences that he was heterosexual. Activists who survived the AIDS era still, to this day, revile Koch. A petition is underway to strip Koch’s name from the Ed Koch-Queensboro Bridge.

While some might criticize the Times for writing about a dead man’s sexuality, the newspaper made the correct decision to publish such an investigation into the life of someone who made a great impact on New York City. This is news. What was missing, though, was any kind of reflection on the Times’ own role in the homophobia that was once ran rampant through New York. Koch was closeted, in part, because the most influential newspaper in America held a fiercely anti-gay editorial line that emanated directly from A.M. Rosenthal, the powerful executive editor. Rosenthal lorded over the Times for much of the second half of the twentieth century, serving as a city editor, managing editor, executive editor, and columnist. A Pulitzer Prize-winner, he died in 2006.

Rosenthal is mentioned nowhere in the Times’ Koch investigation, though no discussion of homophobia in politics is complete without him. What made life so precarious for gay men and women wasn’t merely the prejudices of ordinary people. It was elite opinion, the sort that aligned fully with the everyday, vile fury of the common man. A newspaper newsroom or college classroom could be every bit as homophobic as an Irish bar. In the 1970s and 80s, Rosenthal’s Times even banished the word “gay” from its pages. As late as 1985, after Frank Rich reviewed an autobiographical play by Larry Kramer examining the rise of the AIDS epidemic in New York, the Times slapped on an unprecedented postscript without notifying Rich, proclaiming the newspaper had not suppressed stories about AIDS. A quote was even added from Koch, noting he hadn’t seen the play.

In 1963, the year Rosenthal became the metropolitan editor, the Times published a story with the headline “Growth of Overt Homosexuality In City Provokes Wide Concern.” The reporter, Robert C. Doty, wrote that the “city’s most sensitive open secret—the presence of what is probably the greatest homosexual population in the world and its increasing openness—has become the growing concern of psychiatrists, religious leaders and the police.” A year later, Kitty Genovese would be murdered in Queens, and Rosenthal—in addition to overseeing deeply misleading coverage of the case—actively hid Genovese’s sexual orientation.

Charles Kaiser, writing in the New York Review of Books a decade ago, reflected on the Rosenthal era, noting the top editor was “famously homophobic.” Rosenthal once declined to make a staffer a daily book critic after he found out the staffer was gay, according to Kaiser. “The year before the AIDS epidemic was discovered, there still wasn’t a single openly gay reporter or editor in the newsroom,” Kaiser, a former Times journalist, wrote. “Only after AIDS would it become obvious to everyone that there were gay people in every profession and every walk of life—from the actor Rock Hudson to the notorious redbaiter Roy Cohn.” A shift only began to occur at the Times after Max Frankel succeeded Rosenthal as executive editor in 1986.

“He kept the paper straight,” Rosenthal had etched on his tombstone, an allusion to how the esteemed editor maintained a “defense of high standards of reporting and editing, which called for fairness, objectivity and good taste in news columns free of editorial comment, causes, political agendas, innuendo and unattributed pejorative quotations,” according to the Times. This, of course, was a lie. Rosenthal very much had an agenda, wasn’t fair, and printed innuendo. He was as opinionated as any of the bleeding-heart liberals and rabble-rousers he despised; he was merely fighting for the other side. It would have been beneficial for the Times of 2022 to explore Rosenthal’s legacy—or at least offer a passing mention. The reader gets the impression the paper would rather bury that part of its past. No one is served when investigations are incomplete.

The Rosenthal homophobia had all the horrible ramifications Ross describes, and included firing tremendously promising young reporters or relegating some to minor posts abroad and never bringing them back to New York. It was a devastating witch-hunt, not entirely reversed until Arthur Sulzberger, Jr. brought genuine "family values" of inclusion, compassion and equity to the paper.

I have to admit that I found the profile extremely moving. I don't care for Koch's politics and because he was a politician that was the most important thing about him. His story and personality reminds me of the stories so many other men from his generation (or even the one after) who were closeted, or kept one foot in the closet, or who were out but quiet and ambivalent about their sexuality in a way that is hard to understand today (like Stephen Sondheim, to pick an odd example).

Being *out* was such an effort, such a huge and exhausting statement to make if you were a public figure. Staying *in* was just the normal thing to do if you were gay. Of course I blame Koch for the way he handled AIDS but I can't be angry with him the way the AIDS generation was. He was from a different world.