The Rise of the New Romanticism

On our culture and its discontents

In case you missed it, I appeared recently on The Hill’s “Rising” to talk about how Democrats lost the dissident vote. And if you are new here, my novel, Glass Century, is due out May 6. Please pre-order it. The writer Alex Sorondo has said it is in the running to be one of our great Millennial novels, and I won’t disagree with that. Nell Zink says it’s about “about the only taboo kink left, adultery.” Even better. Get it now!

There is a new Marvel movie out and no one seems to care. No one, of course, is an exaggeration, a provocation, since there are obviously human beings buying tickets to Captain America: Brave New World and a good number who are discussing or even liking the film. More, certainly, are engaging with the Captain than with my cherished literary novels or those spiky political and cultural essays; the nerds have that on us, and don’t you forget it. But there is slippage. It’s not just that the critics have panned the new Marvel movie. Mass audiences have defied the tastemakers before, and the critical establishment—whatever might be left of it—has less power and influence today than at any point during modernity. It’s that this movie doesn’t seem to matter like its predecessors did. Most disturbing, for MCU partisans, are the greater yawns from the masses. This is not a movie that is anywhere near the zeitgeist. This is not a movie that is making its way to many midcult conversations. Harrison Ford turning into the Hulk is like the proverbial tree falling in the forest. If a gamboge, CGI-powered octogenarian screams and no one is around to hear, does he make a sound? Some of this is inevitable; everything ends—or, like energy, it changes form, never quite destroyed. Once, there were Westerns. Everyone wanted to see a Western. They dominated film and television. Tens of millions of American children played Cowboys and Indians. The greatest Western actors were as famous as any president or pope. Only an idiot, circa 1960, would doubt the supremacy of the Western. And then they were gone. We know the Western today and there are still Western-themed TV shows and movies, or those at least paying homage to an earlier time. But the age of the Western, quite obviously, is finished. This will be the fate of the superhero film. There are going to be more of them, many more of them, but few are going to recapture their 2010s glory, when every piece of intellectual property, it seemed, was an international gold mine.

It would behoove Hollywood to pivot. New Hollywood, in the 1960s and 1970s, represents what that might look like: young, ambitious auteurs taking the reins to reinvigorate a medium that, just a few years earlier, seemed to be in a state of drastic cultural decline. There are great films still being released today, but fewer of them emerge from the most powerful studio players. The highest grossing films remain sequels, prequels, and recycled IP; this is an old story, but still one worth emphasizing because it wasn’t always this way. Beyond raw profits, Hollywood had, for many decades, an interest in advancing the culture. That interest, in the 2020s, has plainly slackened. The same is true in recorded music. The major labels are content to coast on their back catalogs and farm cash off to intermediaries. They do not want to invest their resources in living, breathing artists. Discovering and uplifting new generations of musicians is no longer the going concern. Spotify, rife with knockoff AI tunes and easy listening playlists that entice the median listener to forget who the creator of the music might even be, is currently hegemonic, and shapes taste through opaque algorithms. There are still individual artists and albums that matter, but far less than there used to be—there’s a vague sense, even among those not terribly attuned to cultural shifts, that there’s a great macrocultural stagnation upon us. Taylor Swift’s decades-long dominance of the pop charts is less a sign of her particular talents than the reality that there are no longer enough sonic advancements to displace her. Elvis Presley, Frank Sinatra, Michael Jackson, and Madonna all endured, but there were peaks and valleys to their popularity, moments when the public turned away from them or simply asked for something more. Swift faces no such pressure, if even her star will inevitably dim, the hysteric peak of 2023 likely never to be recaptured. And if you are hungry for great art, you aren’t wrong to think that our digital age is producing less of it—at least in the mainstream, where there was once a synergy between the profit motive and creativity, capitalism teaching us, in the twentieth century at least, that we could be a nation of cake-eaters. Now the sugar tastes rather lousy, and might be fake.

There is a great desperation to artificial intelligence. Just as the macroculture withers, seismic technological upheavals no longer seem like our destiny. To Silicon Valley’s evangelists, this is verboten, like rushing into a church and screaming that there is no God. Neil Postman, in his seminal work Technopoly, declared that the United States, at the dawn of the 1990s, was the world’s first “technopoly,” a nation that had subsumed itself to the god of Tech. Postman was not a Luddite; he simply saw what so many technologists couldn’t admit, that there were no moral underpinnings to the new computer age, no argument that rested in universal human values. Technologists were giddy about a future in which humans would be mere tools of technology, denied agency and made ancillary. This was new: the automobile, the airplane, penicillin, and indoor plumbing did not seek to erase the human being in the same way as the computer or AI. Postman, who died in 2003, references AI in Technopoly, which a reminder that the debate around such tech is quite old now, even as the recent advances in generative AI make it all seem like it was birthed from the skull of a deity last Thursday. The current desperation derives from the creeping realization that promises might not be kept. AI will infest our world, but not advance us to any greater planes of development or even saturate on the scale of the smartphone or iPod. ChatGPT, more than two-years-old now, is widely used because its basic version is free; consider how many more Americans, in that span of time, were willing to pay hundreds of dollars for an iPhone. AI itself has been foisted upon the populace, burrowed everywhere, marketed with the zeal of Luther’s Protestantism. None of the tens of billions poured into these ventures has made any recognizable impact on the American economy. AI may well deliver on profound advances in the medical field and enable militaries to more efficiently slaughter enemy combatants, but much of the flickering reality of its presence in our world is that it is performing tasks that have been the province of human beings for many thousands of years. We can already read, write, and create. We can paint. We can publish books. We can make music. What is the purpose of having a machine do it for us? Why? The major tech conglomerates that stimulate and strangle the American economy have a particularly insipid vision for our future: we are slovenly office drones too helpless to even write emails to our supervisors. We are fattened, bloody flesh sacks doomed to obsolescence, pacified by programs that will do all the thinking and feeling for us. If we stop thinking, what is left? To submit? To putter along like amoebae?

AI has what is known as an opacity problem. No one quite knows how a program produces the answers it does to any particular prompts. It’s not so easy to peak under the hood and figure out what went into Claude or ChatGPT’s reasoning. For some technologists, this is exciting. Since human consciousness is still something of a mystery, a blend of hard science and the ineffable, AI’s effective black box carries a certain allure. Yet there’s never much beyond that—no serious explanation for why human consciousness requires such a supplement or outright replacement. Just as the shine has come off the movie superheroes, AI no longer appears to provoke much wonder or enthusiasm from the American public. Gratis, anyone might use AI, but this passive and force-fed adoption does not even approach Facebook’s influence on the culture in the mid-2000s, when millions, very rapidly, decided they needed social media profiles to live their lives as functional teenagers and adults. I’m not terribly triumphant, though, about AI’s relative failure to launch. In fact, the quiet desperation from the likes of Sam Altman, Elon Musk, and other members of the billionaire tech class might represent a new kind of danger because, for them, there really is no going back. There’s no failsafe. Virtual reality failed, Web3 and blockchain never thrived, and there are no new social media networks to replace those that are wheezing along. The high interest rates have reduced much of the froth. In the coming years, if AI cannot metastasize as promised, the oligarchs will lash out like wounded beasts. They cannot accept the inevitability of a world without rapid ascent. Despite what the technologists believe, there are laws of gravity as well as valleys to follow peaks. Nothing is promised to us. We will advance, but not always on their terms. And they’ll find the public growing more recalcitrant.

A little over a year ago, building on the work of the writer Ted Gioia, I proposed we might be entering a new Romantic era. There were subtle signs of a coming shift. The famed mantra of the liberal left in the early phase of the pandemic—Trust the Science—had lost resonance, with hero worship fading for those like Dr. Anthony Fauci and the pharmaceutical behemoths that developed the Covid vaccines. Church attendance, long the barometer of the American devotion to the unseen, had continued to plummet, but the ferocious New Atheism of the 2000s wasn’t taking its place. Instead, a loose “spirituality” was forming—a devotion to astrology, witchcraft, magic and manifestation—that was becoming popular with the young. Online life, paradoxically, had only catalyzed this spirituality more, with teenage TikTok occultists and “manifesting” influencers racking up larger followings. Despite this enmeshment with technology, a backlash was percolating to the incursions it had made into all of our lives. Jonathan Haidt’s The Anxious Generation shot up to the top of bestseller lists. Schools moved to ban smartphones from their classrooms. Covid showed us what was possible if we lived, for months on end, in virtual worlds, and Americans largely learned they hated it. Science is science, not a religion, but for many months in 2020 and 2021 it was treated as one, even as the scientists failed, in several striking instances, to adequately explain and predict the virus in our midst. Trust in the science did not curdle at the same instance as trust in the tech conglomerates, but they are not so dissimilar when weighed against the hype of progress. The new romantics wonder: what good has any of this done for us? Were hyper-sophisticated GPS devices, cameras, and pocket supercomputers worth it? Is it fun to be surrounded by QR codes? It is too soon to predict a revival of the Luddites, but there are small pockets of young people ditching smartphones entirely; anti-tech activism seems, suddenly, to have some momentum. There are indications, too, of a political convergence. On the right, Steve Bannon rails against the “technofeudalism” promulgated by the likes of Musk and Altman. Robert F. Kennedy’s ascension to Health and Human Services Secretary marks the apotheosis of a heterodox wellness movement that casts deep suspicion on pharmaceutical companies and official health science—a movement now right-coded, but one that attracted traditional counterculture thinkers who might have more easily slotted into the Democratic coalition a decade ago. Since Musk is helming DOGE and doing his best to destabilize the federal government, liberals are becoming more polarized against his companies. Mark Zuckerberg lost the left after 2016, when Facebook was erroneously blamed for Trump’s rise, but his new, ham-fisted rebrand as a manosphere autist will probably cement the left’s disdain of Meta. Zuckerberg’s poll numbers can’t be very good.

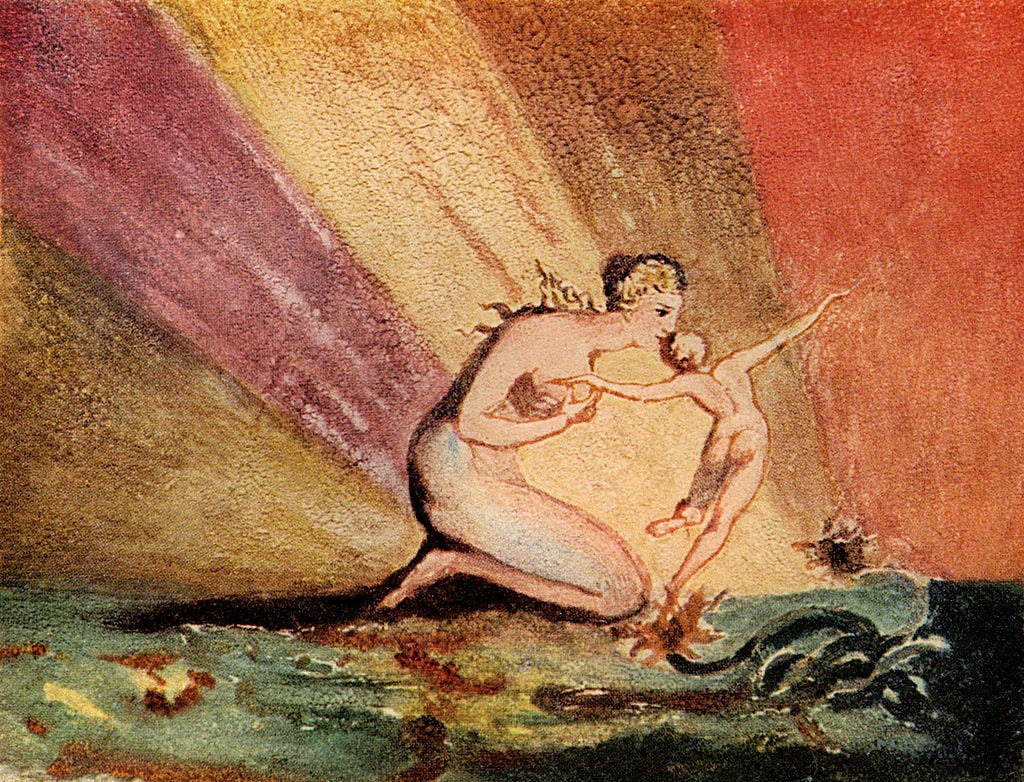

It can be a folly to try to hunt out too many temporal antecedents, but there are at least a few similarities between today’s upheaval and what came in the early nineteenth century. Rationalism, for a time, seemed ascendant, as the rapid technological changes brought about by the Industrial Revolution promised their own algorithmic approaches for daily life. Machines displaced the old craftsmen and the workers that remained were punished through all their waking hours, forced to meet savage productivity goals. The individual, flesh-and-blood human never meant less, now that wonders like the cotton gin and the coal-fired steam engine could accomplish so much. Romanticism was the bloody cry against it all. Luddites torched factories and artists declared war against the principles of the Age of Reason that had seemed to beget the new industrial drudgery. Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein offered a frightful riposte to those who believed science could only deliver bountiful good. Beethoven unleashed radical symphonies of a sweep and emotional intensity that had never been known before in western music. Ann Radcliffe, the English novelist, wrote a prescient defense of terror as a literary device, as the Gothic—dark gobbling light—rushed back into vogue. The poets and painters, the influencers of their age, lashed the old gods of logic and gentility. There were William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge, blasting away at British cultural elites in lyrical ballads, and Percy Bysshe Shelley and Lord Byron hurling between profound ecstasy and crepuscular sorrow in their poetry. William Blake, beset by visions of trees glittering with angels, believed imagination was the most vital element of human existence, and became the herald for generations of metaphysical insurgents and revolutionaries. Ralph Waldo Emerson lectured about the invisible eyeball and the over-soul. Not all of the old romantics were opposed to Judeo-Christian religion, but they were drawn, like the youth of today, to spiritual realms that operated far beyond any biblical teachings or rationalist precepts. They were deeply wary of technology’s encroachment on the human spirit. They feared, ultimately, an inhuman future. Today’s nascent romantics sense something similar. Why else, in such an algorithmic and data-clogged age— with so much of existence quantifiable and knowable—would magic suddenly hold such sway? In Technopoly, Postman cast a wary eye at what he called “scientism,” the drive toward making a religion out of data, and there is evidence of a sharp turn against the optimism that greeted the great rise in quantifiable metrics over the last decade. There is logic to the anti-logic. The new Romantics aren’t stupid.

For now, the rebellion will have to come in the material world. On the literary front, physical scenes have come back to the fore. In the 2000s, the rise of so-called “alt lit” promised a digital scene, one where web pages were gathering points and emails, along with message boards and comment threads, offered communion. Oft-derided now, Dimes Square, so concentrated in Manhattan, was a rejoinder that was at least Romantic in spirit: the pandemic will not keep us from gathering, and so we will make a physical place, again, the setting for something new. The new literary magazines that have arisen over the last few years have made, explicitly, in-person readings and parties a central component of what they do. It is remarkable how popular these readings can be in New York. A small magazine, Heavy Traffic, brought hundreds of people to an art gallery in Manhattan, and The Drift routinely draws that number for their new issue launches. The magazine I co-founded, The Metropolitan Review, will probably hold a very well-attended launch party in the next few months. It is easy to be cynical about the scenesters. I certainly have. But it all qualifies as rebellion: the young are tired of being indoors. They cannot find their future in screens. Perhaps this is an urban phenomenon, or one confined to the most fashionable of cities, but my sense is there’s a greater current here, one that will place a premium, in the coming years, on reality. A final question will be what durable art this all produces, and that question will remain, for now, open. But if I had to identify an early crop of neo-Romantic writers, I would say they are germinating on Substack, properly exploiting the original freedom promised by Internet 1.0 to yank the English language in daring, strange, and thrilling directions. It is safe to say there are few people alive who write like the American novelist and critic John Pistelli, or Sam Kriss, the British writer with his mystical, warlock-ian bent. No one is attempting such a far-reaching metafictive project as Justin Smith-Ruiu, the American academic who teaches in Paris. They are making their own vanguard.

What the new Romanticism does promise is a scrambling of left vs. right. Better to imagine the new age as either up vs. down, border vs. center, or unreality—or managed reality—against the light, water, air, and consciousness we’ve tried to protect. It’s notable Zuckerberg’s Metaverse quietly failed, that no one talks anymore about the namesake technology that was supposed to resuscitate the billionaire’s brand and usher us all into a Valhalla of glorious VR headsets and pixelated villages. Zuckerberg might want to pretend there never was a Metaverse, just as Apple might want to memory-wipe anyone who remembers the Vision Pro. These are catastrophic, embarrassing failures, and the AI mania has mostly relegated them to historical curiosities. But we should remember what the richest men in the world wanted to do, and what they wanted from us: to disappear out of our reality and into theirs. Already terminally online, we had not yet given enough of ourselves—not for Tim Cook, Mark Zuckerberg, or Sergey Brin. No oligarch class in American history has been so nakedly parasitic. The Robber Barons, at least, could leave oil and rail bounties behind, and Andrew Carnegie built thousands of libraries. Today’s tech barons, for a variety of reasons, seem to resent the humanity in their midst. Human agency itself is a problem to be optimized away. Recognizing this is not a liberal or conservative notion; proponents of capitalism and socialism can be equally alarmed. What is most startling, arguably, is the stunted imagination of the tech elites, their fundamental inability to fathom utopias for the human race. They aren’t promising us wonders that will free us from the drudgery of work and they aren’t working, in concert, to eradicate poverty or dismantle the military-industrial complex. They have not produced medical marvels to end the most virulent diseases. They do not plan new cities. At best, like Musk, they long, child-like, to escape the Earth altogether, with little sense of how this would make billions of people better off. They are a reason why there is any new Romanticism at all. They’ve designed better and more efficient nooses than anyone in recorded history.

Downstream from it all is the culture itself—literature, music, cinema, the visual arts, and television. All that still, in varying forms, nurtures us. The tech advances of the last decade and a half have curdled these offerings. The analog age knew faster cultural advancements, more brio, and greater experimentation at the level of mass entertainment. The institutional machines, for all their avarice, could be trusted then. Now we beat on into a murkier future. There is good news still, flickers of light in the fog. A serf cannot liberate himself until he knows he’s a serf. He must survey the land, his life, and his relation to power to see that he must get free. That is as hard as breaking the chains themselves. A decade ago, there was not much of this. There was a poppy effervescence about tech, an Obamaian optimism about how we could be made a tool of these conglomerates and it would all, somehow, sort itself out. Now we have woken to the world in front of us. Illusions are melting away and we are, for all of our flaws, a less deluded people than we were before. It is difficult to know what shape this era will take and what dangers may be in store. It is difficult to know how much more slop might be forced on us, and if we will choke on it all. I am sure, at least, we aren’t finished. Human agency hasn’t been snuffed out. There is a world, as sickly as it might seem, to still win.

Hello. Substack is turning me into a true haunter of the literary vs. technological discourse, and I’m fascinated by everyone’s takes.

I’m curious about this critique of cultural stagnation, technological overreach, and AI’s failure to deliver meaning—yet it never interrogates how this critique itself is shaped by the same system it laments. This isn’t a flaw in your thinking—it’s the nature of the landscape itself. The critique isn’t separate from the system; it is produced by it.

There’s an underlying nostalgia here—a longing for an era when capitalism “did creativity better,” when artistic ambition felt grander, when cultural production seemed to work in ways it no longer does. But this isn’t just about cultural decline; it’s about a fundamental shift in human cognition.

Meaning isn’t collapsing due to poor artistic vision or corporate laziness; it’s shifting because cognition itself is no longer individual, but externally scaffolded, algorithmically mediated, and nonlinear. The frameworks we use to evaluate art might not even apply anymore.

I feel like the “New Romantic” argument assumes we still have static agency—that we can “pivot” to a new artistic mode that incorporates elements of the old, as if resistance is just an aesthetic choice. But when the brain itself is becoming more algorithmic—pattern-seeking, nonlinear, hyper-vigilant—how much of this ‘resistance’ is just another performance within the system? If the critique itself is mediated through digital structures, then what does it mean to position yourself as outside of them? You diagnose the symptoms but ignore the deeper rewiring of perception itself.

Assuming physical spaces inherently produce more “real” artistic engagement ignores that these spaces have always been gatekeeping mechanisms. Who gets to be in the room? Who never even gets an invitation? The idea that young people are “tired of being indoors” universalises a particular kind of digital alienation while erasing the reality that, for many, the internet has been the only place their voices have ever been heard.

Bringing back "the Romantic"—or even theorising its mutations—isn’t radical. It’s an old model that has always prioritised social capital over artistic innovation. Of course, in-person artistic communities matter, but framing them as the primary mode of cultural production ignores how digital spaces have already redefined participation, accessibility, and influence. Meaning isn’t tethered to a single location. It exists in both digital and physical spaces. Pretending otherwise isn’t rebellion—it’s nostalgia for a world that never functioned the way you want to remember it. And that nostalgia, ironically, hazes out the very people you want to reach.

And this is what makes the argument not just misguided, but ironic. Because what happens after the readings, the literary gatherings, the in-person artistic movements you champion? They are documented. Uploaded. Reviewed. Clipped. Stored. Shared. They enter the same digital pipeline as everything else. The very internet you claim to resist becomes the scaffolding for your legitimacy.

So what exactly is being reclaimed here? That meaning only exists in a room full of the right people? That literature is only “real” when spoken in one specific postcode—before inevitably being archived and distributed through the very technology you dismiss?

And this is why the rejection of meta isn’t about rejecting complexity—it’s about rejecting hierarchical control over meaning. The tech overlords want predictability. That’s why they are scrambling to impose rigid structures on a system that is inherently slipping away from them. The real battleground isn’t digital vs. physical—it’s the fight to keep meaning fluid, decentralised, and ungovernable.

Rebellion, if it’s going to mean anything, can’t be a retreat into the past. It has to confront the actual structures of control in the present. Otherwise, it’s just an aesthetic exercise—a salon, a room full of the same people talking about the same things, waiting to be archived.

If this critique is meant to illuminate rather than lament, it has to reckon with the conditions we’re actually working within—not the ones we wish still existed. Resistance isn’t nostalgia. It’s adaptability.

Would love to chat further if you're interested. Thanks for helping me think. xxx

A tour de force; you should read it. I realize I'm biased because I substantively agree, but I want to praise the structure of this essay. You ease from popular culture into world historical, questions, so that the reader isn't saying "yeah but" from the outset. You also get the tech and the economics quite right, which is no small feat. And you leave us with a grim synopsis, but real hope, too -- and that is indeed the state of play, as I see it anyway. Bravo.