The Tragedy of Jordan Neely

What a subway killing says about policing, the law-and-order right, and the progressive left

Before Jordan Neely was choked to death in a New York City subway car, I was going to write about Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and the recent bump in NYPD pay. There was, I believed, something curious about the progressive and socialist left furiously converging around the issue of a unionized workforce receiving a pay increase. I understood, fully, why it happened—Defund the Police retains many followers, there’s a century-old debate over whether police should belong to the labor movement, and NYPD officers genuinely abuse the overtime system, boosting their pay just in time for an early retirement around 42 or 43—and where the discourse would head, but this didn’t make it any less counterproductive for the leftists who have built tangible power in New York but find themselves running up against certain limitations of geography and even income. This is a point I very much want to return to, and will eventually—first, however, there is Neely’s death.

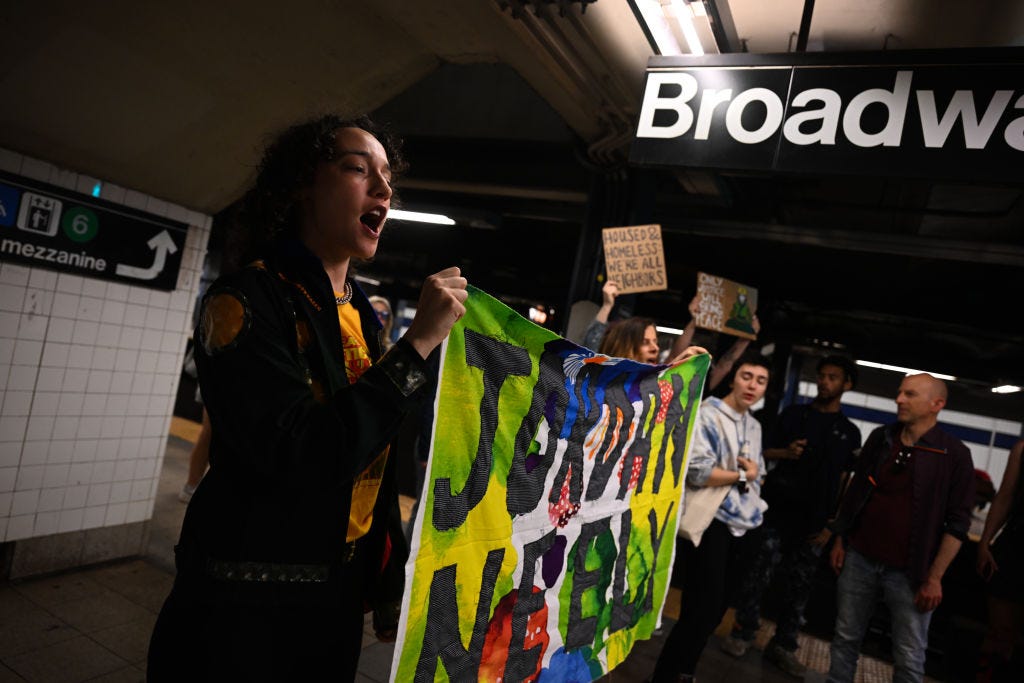

We still do not know many details. But we know enough to sketch an outline. Jordan Neely was a 30-year-old homeless man who had once been a gifted Michael Jackson impersonator. He was ranting on an F train in Manhattan, telling passengers he didn’t want to go back to jail, he was hungry, and he was ready to die. What happened over the next several minutes is not clear. At some point, Daniel Penny, a 24-year-old white Marine veteran, placed Neely, a Black man, in a chokehold and took him to the floor in a minutes-long struggle that ended in his death. Penny was not initially identified and police did not arrest him. The racial dynamics of the killing recalled, for many, the Bernhard Goetz subway shooting of 1984, with reactions polarizing along similar political lines. Many New Yorkers, especially on the left, were horrified. The leader of the progressive Working Families Party called Neely’s death “a modern-day public lynching.” More moderate and right-wing voices either avoided condemnation—Mayor Eric Adams, a former transit police officer, was among them—or outright defended Penny’s actions, arguing working-class people are fed up with disorder in the subway system. Progressives, including veterans of the Black Lives Matter movement, called for Penny’s swift arrest and prosecution. Adams, meanwhile, fumed at Brad Lander, the left-leaning city comptroller, for calling Penny a vigilante. The Medical Examiner ruled Neely’s death a homicide.

What we know, so far, is that Neely was not armed. If he was not brandishing a gun or a knife, Penny’s defenders have little to rest their case on. Chokeholds and restraints can be employed without killing a person. If Neely was merely verbally threatening, passengers could have chosen to leave the car at the next train stop. The F was passing through Manhattan, at Broadway-Lafayette, and stops along that line are very frequent. Neely simply did not have to die. I grew up in New York City, still live here, and I’ve unfortunately encountered many men and women like Neely in my time in the subway and walking the streets. In recent years, the problem has gotten worse, with the concurrent rise in homelessness, the destabilizing nature of the pandemic, and the deficit of adequate mental health services. The lack of suitable institutions, including housing, for the mentally ill is a tremendous public policy failure that dates back a half century. Not all homeless suffer from mental illness—many, in fact, do not—but struggling in such a way will likely lead you to the streets, especially in a place as expensive and unforgiving as New York.

The politics of this all, when you survey it from a slight remove, grow somewhat confounding. There is a strong overlap between those who are calling for Penny’s arrest and prosecution (a very defensible position) and those who have wanted to defund or abolish the police entirely. Police abolitionists hold the most confused position here because someone in a uniform is going to have to put Penny in handcuffs and force him to show up for his trial. A professional prosecutor will need to try his case. A Defund advocate, meanwhile, might say this is what the police are for, to make the just arrests and do their duty in these particular instances. A scaled back police force can still arrest Penny. They will argue, fairly, more mental health services are needed so problems like these never happen in the first place. But supporters of Defund have often argued that police have little function other than to impose state-sanctioned terror and that large, well-funded institutions like the Manhattan district attorney’s office are fundamentally invalid, existing chiefly to force Black men and women to Rikers Island, the city’s notorious jail complex. It is understandable, if odd—given the mass protests of 2020—that the very same people chanting for diminished police are now on the side of arrest and prosecution.

Conservatives and law-and-order types are hypocritical in their approach and disturbing in their bloodlust. Is Penny a vigilante? If you believe he was meting out justice, then yes. Penny is not an NYPD officer. He’s not even active duty military. In every sense, he was taking the law into his own hands. If you support the concept of a well-funded police force that has a state-sanctioned monopoly on violence in a major American city, how is any of this defensible? How is it good for the NYPD that a Marine veteran believed it was fine to restrain a man to the point of death? Neely’s criminal record doesn’t make the death valid. No past arrest would justify getting choked to death like this—certainly not in New York, where the death penalty has never been employed.

The crux of this all is simple enough: many people only want law-and-order for their perceived enemies. A conservative who otherwise decries bail reform, progressive prosecutors, and clemencies for prisoners hopes Penny can walk free. They may even want to celebrate him, as they once did for Goetz. Breaking the law is fine as long as the right person is doing the breaking and the wrong person is being punished. A Black homeless man is a sufficient target. Since Penny wasn’t shoplifting from a CVS or taking illegal drugs, his crime is worthy of exoneration.

Progressives swept up in the fervor of 2020 have their own reckoning to undertake. A mass movement was built upon the concept of drastically reducing policing. Some of the most radical and vocal factions of this movement called for the end of all prisons and police. They cast doubt on whether a criminal justice system should even operate in the United States, if the pursuit of prosecution and juries and trials should exist. The trouble, of course, is that the world is a very complex place, and sometimes it’s the people you don’t like (or like) who need to be brought to justice. And who does that bringing? In a world without prisons or police, where is the accountability for Penny? Who tries him? Who puts together the jury pool? Who jails him, if he’s found guilty? Who pays for all of this? Absent the flawed procedures we have, there is mob justice. The criminal justice system, indeed, requires great reform. The NYPD remains hyper-militarized and far too unaccountable to the public. Reform, however, should not equal anarchy.

Finally, there is the difficult question of how to treat the mentally ill. Adams angered many on the left when he announced last year that police and emergency medical staff will begin forcefully hospitalizing people on the street who appear to be a danger to themselves. Forced institutionalization has many critics. The involvement of police can inevitably lead to violence, as it did in the tragic killing of Deborah Danner, an elderly woman who struggled with schizophrenia. There are no straightforward solutions. But there are people who may harm themselves or others if there isn’t forced intervention. Mental illness itself does not allow for clear decision-making. Jordan Neely should not have spent his last years on the streets, in the throes of crisis. He should have been in a safe facility receiving treatment. How to get men like Neely to professional treatment is a practical and political question. Police, in many instances, don’t have the best training or even the temperament to do it. A social worker, though, is not going to want to face down a potentially violent situation alone. Pairing police and mental health professionals together seems like a logical solution, and one that will cost money—money, the Defund advocates at least, may not want to spend. Conservatives will balk too. Solving this crisis will cost many billions of dollars. New psychiatric facilities will have to be constructed. A healthcare system in which psychiatrists refuse Medicaid will have to be revamped. Can the political will be summoned for any of this? Or will this tragedy simply give way to the stasis know now, the one that led to the death of a young man on a subway car?

Here is my perspective. I lived in New York (from 2000 to 2005), took the subway almost every day (often multiple times per day), and was immensely grateful for the freedom that the subway provided. It was also, I'm sure, a relatively good time to be a subway rider in New York in terms of safety.

Having said that, there were at least 4-5 instances during those five years where someone was acting dangerously erratically or simply intentionally intimidating other people in the subway. And while I was never particularly worried for myself personally, I can absolutely remember being terrified as I thought about what I was going to do if the situation became truly violent and the person began to physically attack another rider, particularly a woman. I remember thinking how I would have to do something (the Kitty Genovese story made a huge impression on me as a teenager; and I vowed never to sit back and do nothing while someone was attacked like that), but how awful it would be to die or be seriously injured because I happened to be on the train with the wrong person and got knifed or shot trying to help. I remember desperately looking around the train trying to figure out if who if anyone would come to my aid if I intervened and how we could coordinate action.

In those moments, I can't tell how much I wished there was someone like Daniel Penny on the train with me, especially someone who was willing to take that first (and by far the hardest) step forward to intervene. I feel badly for Jordan Neely, who obviously was the victim of tremendous misfortune in his life. I absolutely wish that that his Mom had never been killed, that he had a stronger family to rally around him when it did, and that our society had better systems and programs for dealing with the mentally ill as he got older and became more and more unbalanced. I strongly support higher taxes to make such programs possible.

But I absolutely draw the line at tolerance of the threat of physical violence toward others. There can be no tolerance of that in society, particularly in spaces like the subway. And so I'm grateful that Daniel Penny was willing to step forward in that moment, especially since I know I would not have the physical courage to take that first step. But I'm also sure I would have been one of the people to step forward to assist Penny as he tried to keep Neely subdued by holding Neely's arms. And while I absolutely wish Neely had not died, if I'm being honest, in that situation I would not have wanted Penny to release him before we were all certain that Neely was no longer a threat, even if it risked serious injury to Neely.

The same people I see weekly with a table in the park calling for the abolition of policing and incarceration, this week had a table this week calling for Penny to be arrested and incarcerated. I'm not using a metaphor here, this literally happened.