The Worst of All Worlds

The post-Moses malaise of New York

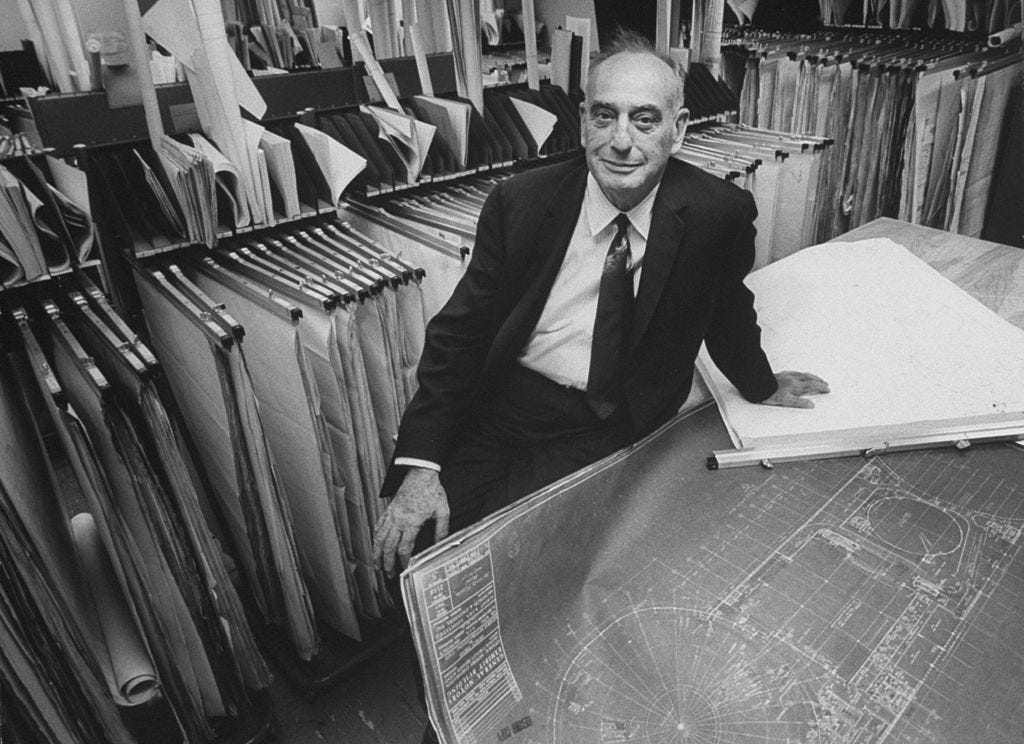

Should Robert Moses be blamed for all the urban failings of the twentieth century? Robert Caro’s The Power Broker, in all its majesty, ultimately answers yes, and it’s this version of history that has dominated among politicians, planners, and city residents since Moses’ death in 1981. Jane Jacobs, his old adversary, has more of a sheen to her legacy, and many more New Yorkers are happy to identify with her successful battles to save Greenwich Village from a horrific expressway. Since Jacobs bested Moses and was right on the merits—an elevated highway through Washington Square Park would have been a monstrosity—it’s easy enough to assign hero and villain roles and move on. Moses, the soulless titan, cared little for people, and it was Jacobs, in her homespun manner, who fought for the little guy.

Or was it so? “The most reductive popular accounts place Moses on the right and Jacobs on the left: Moses the racist prophet of automobility versus Jacobs the anti-authoritarian activist,” writes Sam Stein, the author of Capital City, in N+1. “But one can just as easily present them in the opposite light: Moses, the builder of public housing, pools, and parks, who partnered with labor leaders like Abraham Kazan to build up the city’s social housing stock; Jacobs, the champion of small-scale capitalist enterprise and critic of big government who garnered the admiration of conservative luminaries like William F. Buckley.” Stein, in his penetrating assessment of Jacobs and Moses and those who’ve wrote about them, comes to the conclusion that both famous New Yorkers were too heterodox to neatly organize in any sort of contemporary political context. Each were singularly brilliant. Moses wrought far more destruction, but left behind a tangible legacy of subsidized and public housing that Jacobs, in her defense of the city-as-village, would have little use for.

From my twenty-first century perch, Moses’ greatest sins were twofold: building too many highways and neglecting public transit. But as Stein points out, it was not Moses alone who was blasting apart neighborhoods with megalith expressways, ripping up trolley lines, and defunding mass transit. The federal government in the postwar period believed fully in the future of the automobile. Every major city saw an expansion of roadways at the expense of rail. “If we take this approach and look beyond mid-century New York, we see that many of the transformations that took place in New York also occurred in most cities across the country (and to some extent throughout the world) at about the same time,” Stein argues. “Highways plowed through neighborhoods. Large tower-in-the-park developments replaced low-rise density. Masses of people we displaced.” This isn’t to downplay, in any manner, what Moses did do in New York. The most tragic chapters of The Power Broker, like the Cross-Bronx Expressway’s obliteration of East Tremont and the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway’s blighting of Sunset Park, are always worth rereading, as well as Caro’s damning assessment of Moses’ decisions to kill plans for commuter rail lines down the middle of the LIE and over the two bridges linking Queens and the Bronx. Growing up in Bay Ridge, a neighborhood ringed entirely by Moses highways and split apart by the gargantuan approach for a Moses bridge—the Verrazzano-Narrows, once the largest suspension bridge on Earth—I was keenly aware of how the Master Builder radically reshaped the topography of my city. And I mourned, in my own way, what was lost, particularly when I learned that planned subway expansions from a hundred years ago were never completed because Moses took no interest in them and the city, in the 1970s, ran out of money.

But there’s no reason, really, why those proposed subway lines—trains to the Nassau County border, down Utica Avenue, down Nostrand Avenue, over to College Point, tracing the Van Wyck Expressway, and across the bay to Staten Island—couldn’t have been built in the 40 years since Moses died. London, Tokyo, and Rome build new train lines all the time. New Yorkers don’t quite fathom that they travel around on a public transportation grid designed for a city of the 1910s and 1920s. In fact, the New Yorker of 1923, sans automobile, had more transportation options—outer borough street trolleys and elevated subway lines running up and down Manhattan, including along the Second Avenue route politicians have spent the last 100 years, literally, attempting to recreate in piecemeal fashion. A New Yorker, before 1950, was always being treated to new marvels of infrastructure. And these subways, tunnels, and bridges were built in rather rapid fashion; the new Hudson River tunnels will take a longer time to complete than their twentieth century antecedents. All of this is deeply dispiriting and embarrassing. It is exciting that Gov. Kathy Hochul wants to build a new commuter railway in Brooklyn and Queens, but there is no serious timeline attached to the project and it will likely end up taking longer than any of the subway digs of the early 1900s. I don’t have a good answer as to why, other than that New York wastes astronomical sums of public dollars on relatively straightforward infrastructure initiatives. In a wise and just world, all of this work would be farmed out to foreign experts.

Recently, I found out the walking and biking path at Marine Park, one of the great and overlooked gems of New York City, is undergoing a renovation. Full laps, this summer, won’t be run on the track. I wondered how long the construction would last and went on the Parks Department website. Unlike in Moses’ time, this kind of information is accessible and kindly spelled out. How long do you think it will take this city to renovate a 2.5 mile oval? Five years, apparently. The design phase of the project began in 2019; ground was broken this June. Construction is expected to end in September of 2024. All of this will cost at least $10 million. It’s enough, sometimes, to make you long for the ghost of Moses to trundle out of his grave and get this city back on track. But that’s a simpleton thought. There can never be another Robert Moses because city and state governments aren’t structured like that anymore. One tyrant can’t chair a dozen different departments and commissions. There is much more democracy today, and that’s good—other countries with better functioning democracies than ours build much grander and more efficiently. Italians, British, French, and Japanese don’t long for any Moses-like men to get stuff done. It’s not needed. They have saner procurement processes and streamlined layers of government. Federal and local officials cooperate with relative ease.

One of Stein’s most trenchant observations is that Moses and Jacobs would have, for different reasons, loathed Hudson Yards. The West Side megadevelopment was a signature project of Michael Bloomberg’s mayoralty. Enormous sums of public subsidies were channeled towards building out an entirely new neighborhood near a neglected railyard. At one time, Bloomberg was hoping to lure a stadium there for the Olympics and the New York Jets, but New York lost out to London and the Jets stayed in New Jersey. Today, Hudson Yards is an intriguing but ultimately wasteful expanse of luxury housing that is largely unoccupied and office complexes that will probably never, in this post-pandemic world, reach full capacity. Bloomberg did pump city funds into a one-stop expansion of the 7 train to Hudson Yards, which was treated, at the time, as an ingenuous feat because New York has added so little subway capacity in the last hundred years. I remember attending the ribbon cutting and riding one of the inaugural trains. I could pretend, for a moment, I was witnessing history.

Hudson Yards wouldn’t impress Moses because there isn’t any public housing. Like a Roman emperor fixated on the next millennia, Moses was conscious of creating durable goods for the masses. He also wouldn’t have cared for an extra subway stop, given his obsession with automobiles. Hudson Yards, as Stein points out, would have also flown in the face of the “kind of urban development Jane Jacobs defended in her conflicts with Moses and other advocates of large-scale redevelopment. It was built all at once rather than slowly over time, and it contains only new buildings, rather than a mix of old and new. “ Bloombergians, though, loved invoking Jacobs and Moses when forcing through Hudson Yards. Their approach to housing development was intended to merge the best of both worlds; an attention to detail and neighborhood context while still building big. In actuality, Bloomberg’s development policies helped fuel the crisis the city finds itself in today, with exploding asking rents and surging evictions. Rather than build everywhere, the Bloomberg administration selectively downzoned wealthier neighborhoods in the outer boroughs. Luxury towers would transmogrify the Brooklyn and Queens waterfronts while single-family home neighborhoods successfully retained their 1950s character. Affordable housing, for the Bloombergians, was never much of a priority, and many of these new condos would house, almost exclusively, a well-heeled professional class. And the wondrous new parks—Brooklyn Bridge, the High Line—would be cultivated where this professional class liked to flock. Moses, meanwhile, dreamed of turning the ash heaps of Flushing—that dark valley of Gatsby lore—into the greatest public park of them all. Take the train to Flushing Meadows Corona Park today and enjoy the sights. You won’t be disappointed.

You are echoing what Aaron Gordon wrote on his Substack earlier this month: "New York has become a city of second-hand policies implemented by third-rate politicians playing with yesterday’s ideas. Behind on everything and late to every party, New York is being governed on tape delay."

One reason for why it takes so long for city-controlled transportation improvements to happen is a relative new obsession with community consultation. We used to just trust experts like engineers and planners. Now we undercut them by letting every moaner and complainer have their say in endless public meetings. Exhibit A: McGuinness Boulevard. None of this is necessary. We don’t insist the public weigh in on where we put vaccination sites or when the trash gets picked up, do we?