These Things I'll Be

Brian Wilson 1942-2025

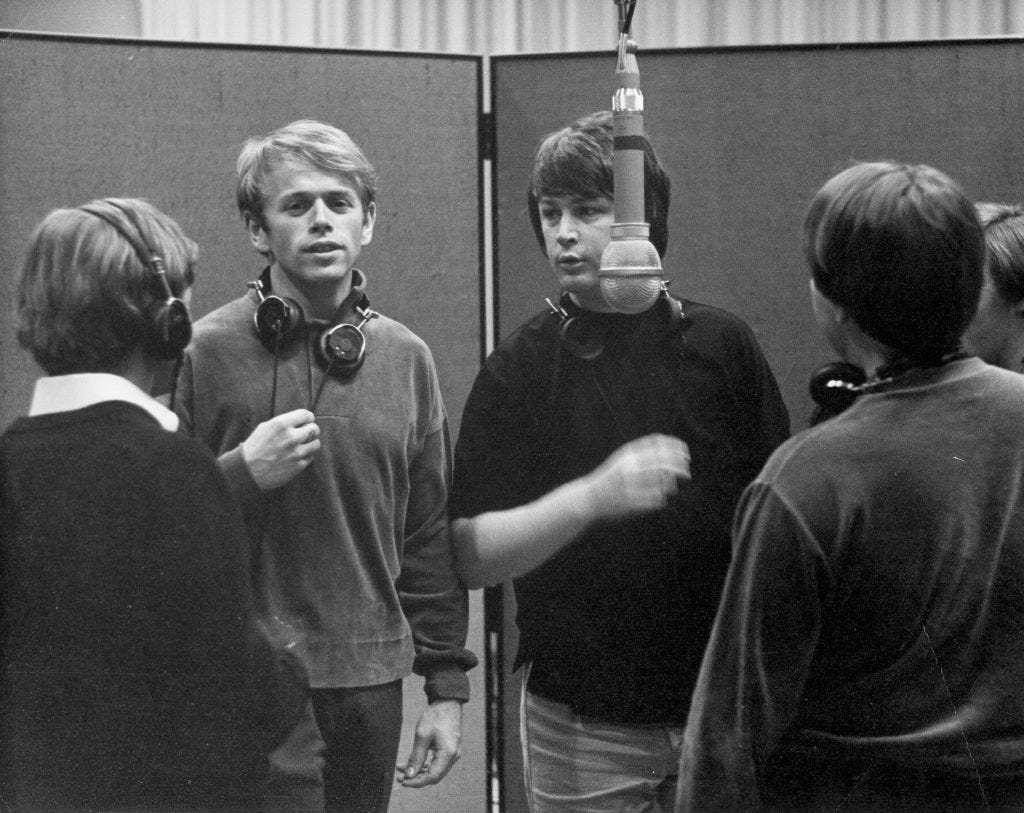

Brian Wilson was more than the Beach Boys, and the Beach Boys were more than Brian Wilson. Both statements are equally true. From the fall of 1962 through the spring of 1977, no American band unleashed a more glorious, glittering, and confounding catalog of music; no one, really, could be their equal. This catalog cannot exist without Brian Douglas Wilson, the working-class son of Hawthorne, California, who dreamed in five-part harmonies and married Mozart with the Top 40. The songs you know were written by Brian, produced by Brian, and sung, somewhere, by Brian. Before Brian, no artist was writing, arranging, and producing their own songs. Capitol Records never wanted to cede any power to a moon-faced kid barely out of high school, but they were forced to reckon with Brian’s genius and bend to his wondrous visions. For a glorious period, all of his ambitions and neuroses could be channeled into music that was played regularly on the radio and beloved by millions. There is a narrative, entirely wrong, that the Beach Boys stopped making great music when Brian drifted into mental illness and drug addiction. Pet Sounds was a pinnacle, sure, and the world of the Sixties lost a great deal when Brian could not finish Smile. But Brian had taught his brothers, cousin, and childhood friend well. For a time, the Beach Boys were even a multiracial juggernaut, with Brian’s brother Carl recruiting South Africans Blondie Chaplin and Ricky Fataar to join the band. In the early 1970s, with Brian in seclusion, the Beach Boys emerged with three albums—Sunflower, Surf’s Up, and Holland—that were as sparkling as any recorded by a rock band in the last fifty-five years. Brian was not wholly absent, and his contributions, remembered by the die-hards and left out of the popular consciousness, were of a breadth and beauty—celestial in their reach—that can never be adequately described. Listen to the second movement of “Surf’s Up” and the coda of “'Til I Die” and report back. That is the miracle of music: Brian is gone, but his aural majesties live on. As long as there is sentient life on Earth, he and his bandmates will be heard.

In 2022, I wrote about 7,000 words on the Beach Boys, and in light of Brian’s death, I am sharing the essay again.

Sixty years after they first walked into a studio, the Beach Boys still exist. They became a band before the Kennedy assassination and they’re still a band today, in the waning months of 2022. They will be one, probably, until most or all of the members die. There is nothing morbid about this, nothing venal. They’ll play as long as people will pay to listen, and the people will pay. No band embodies a nation, but the Beach Boys came close. America, in all its bigness and brilliance and failure, pulsed through them always.

Last year, I reviewed a new documentary about the Beach Boys, one that left me cold. But it was an excuse to write, anew, on the band that has transfixed me like none other.

Writing on the Beach Boys can feel like writing on America. The task, if done right, is immense: so much sublimity, so much sprawl. There are facts that can be recited, that must be entered into the ledger—that the Beach Boys were founded in 1961 and never, on a technicality, broke up, that they defined the early and middle 60s with their surf guitars, empyreal harmonies, and strikingly complex arrangements, innovating pop like few artists before or after; that they were mostly a family affair, three Wilson brothers (Brian, Dennis, Carl) managed by their abusive father (Murry), and a first cousin penning lyrics and singing lead (Mike); that Brian, the oldest brother, born two days after Paul McCartney, was the American Mozart, driving the band, repeatedly, to the top of the charts while reimagining the very nature of recorded music; that the band, at its peak, rivaled the Beatles, and may have scraped higher artistic peaks; that they were from the unfashionable Los Angeles suburb of Hawthorne and, through their music, transformed California into a dreamworld, despite their inner anguish; that they made Pet Sounds, entirely conceived by Brian, which is widely considered one of the greatest albums ever recorded; that Brian, not long after, descended into mental illness; that Charles Manson once recorded music in Brian’s home studio.

And finally, earlier this year, I wrote a mediation on genius that served as a reminder of Brian’s overlooked creative coups: the albums Beach Boys Today! and Summer Days (And Summer Nights!!)

Sixty years ago this month, The Beach Boys Today! appeared in record stores across the country. The Beach Boys were, in 1965, one of the very few American rock acts to stand up to the British Invasion; they were not only pumping out top ten hits but innovating on the plane of the Beatles or even, arguably, beyond them. John Lennon and Paul McCartney were slightly in awe of All Summer Long, which had appeared a year earlier, and while millions knew the Beach Boys for their cheery odes to surfing and hot rods, musicians understood there were other forces at play: this was an auteur’s band, and the meticulously layered sound—with its ingenuous harmonies, unexpected jazz chords, and startling array of classical instruments—was not quite like any that had been heard in popular music before. Brian Wilson, then barely out of high school, was writing, arranging, and producing these albums—such audacity, at a time of oppressive studio oversight, was unheard of—and he seemed to be, at that moment in time, an unstoppable force in pop, as if Mozart had been transported to the twentieth century and reared on rock and doo-wop. Pet Sounds remains one of the great pop albums in history, and Today!—particulary the second side—is every bit its precursor. In songs like “Please Let Me Wonder” and “Kiss Me, Baby” and “In the Back of My Mind,” Brian is at his glorious, neurotic peak, teaming with Mike Love and his swaggering younger brother, Dennis, to sing on the psychic pain that comes with young love. At the end of 1964, Brian had decided to stop touring after having a nervous breakdown on a flight to a concert. In the popular imagination, it’s Pet Sounds that came from Brian’s retreat to the studio, but the first actual product was Today! It kicked off a stunning two-year period of songwriting for Brian—you may have heard another 1965 hit of his, “California Girls”—that culminated in Pet Sounds and their million-selling single, “Good Vibrations.”

When I think of Brian, who has rightly been declared a genius, or the twin titans of the Beatles, I am always struck by the reality that all of them grew up in relative cultural backwaters. London was, and remains, the center of the British universe. If London were removed from today’s Great Britain, poverty and woe would be left behind. To have the preeminent rock band of the twentieth century be English but not of London is still hard to fathom. Londoners themselves may have been befuddled by a Liverpudlian invasion. And the Beach Boys, if of Los Angeles, were reared in the unfashionable suburb of Hawthorne, near LAX. Hawthorne is not Beverly Hills or Hollywood. Three siblings from one of its unassuming bungalow-style homes emerged to transform American pop music. The Wilsons, like Lennon and McCartney, did not attend exclusive schools or have access to any great wealth to burnish their ambitions. They had parents who took a keen interest in music, which helped, but they were, at best, working-class kids who might have ended up in the machining business like their father if rock music never worked out.

A lovely tribute! I wonder if a present-day Wilson or McCartney would find it as feasible to rise from humble origins to global superstardom - I fear not.

Both Brian and Sly were enormous talents that defined the 1960s. I think some serious serendipity or Kismet is at work here...and Jah let them live until the age of 82... lets play Stand and God Only Knows What I would be without you....😎