To the Other World

On Akira Toriyama and the influence of Dragon Ball

When I was a child, around eleven or twelve, my father would take me to Blockbuster. It was the sort of place you could wander through for an hour if an adult wasn’t there to gently remind you it was time to go. I always knew, in that period at least, what I wanted to buy—not rent—or, more accurately, what I wanted my father to buy for me: Dragon Ball Z VHS tapes. They contained episodes I had watched already on Cartoon Network. But it was important, like possessing any talisman, to have the physical tapes, to not only rewatch but collect them, amass them in colorful rows on my bookshelf. To leap forward into the future, my father had to take me somewhere else—a local video game store, several streets down from Blockbuster, that sold bootleg Japanese VHS tapes. Since not all of Dragon Ball Z had aired yet in the United States, I could only know about the series’ full progression through these tapes. Subtitled, with Japanese commercials for candy and cleaning supplies thrown in, they offered me a thrilling, grainy window into what I could expect. I saw the villains who had not yet arrived on American shores and the terrible sacrifices my heroes would eventually have to make.

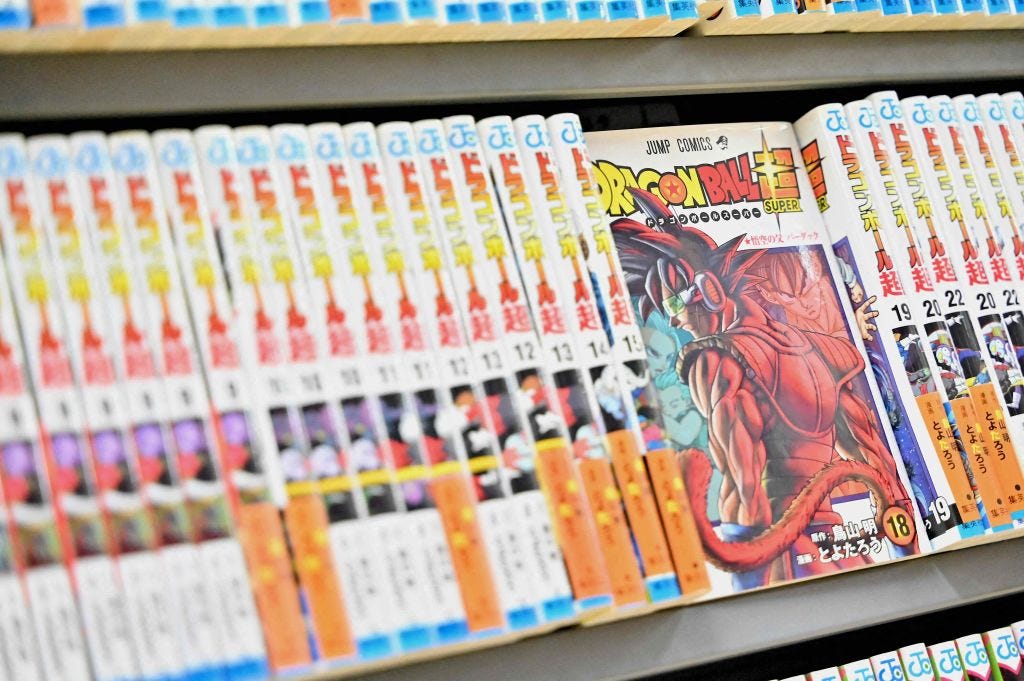

I collected the action figures. I subscribed to fan magazines. I played the video games. I read the manga, once it arrived belatedly in the U.S. I inhabited fully the universe a man named Akira Toriyama, who died last week, had first dreamed up in the 1980s. A giddy visionary who blew open the minds of a generation, chiefly my own, Toriyama was a fusion of Disney and Tolstoy, weaving together fantastic and dizzying story arcs that spanned decades—in Dragon Ball lore, they were called sagas—and made, in their own way, a mockery of the cartoon entertainments offered in America. Almost all anime, manga, and martial arts tropes, in one form or another, sprung from Dragon Ball; after Hayao Miyazaki, Toriyama was the most influential Japanese artist who ever lived. Other kids chased after the X-Men, Spider-Man, Superman, and Batman. I was cared most about Goku, Vegeta, Gohan, Piccolo, and Trunks. I couldn’t look away from Frieza, Cell, and Majin Buu. I wondered, for a period, when androids were going to gain sentience and start killing all of us. Before I ever knew I wanted to be a writer, Dragon Ball Z was there, instructing me on plot, character, world-building, and the glories of propulsive, interweaving narratives.

Dragon Ball, originally a manga (a Japanese comic book series), told the story of Goku, a child-warrior with a monkey tail modeled on the hero of Journey to the West. Like Moses—and Superman—Goku is discovered as a baby on Earth and adopted. And like Superman, Goku is really an alien sent from a planet that was blown to pieces. Here the narratives diverge: Goku’s people weren’t science-worshipping Kryptonians but a savage, warrior race known as the saiyans. Saiyans loved to fight and kill, and most served as mercenaries for a sadistic intergalactic emperor named Frieza. The saiyans toiled for Frieza and resented their subservience. Frieza reveled in the destruction they wrought but secretly feared them. Humanoid with tails, they were able to transform into Godzilla-sized apes during a full moon. Goku’s father, one of the nobler saiyans, decided to lead a rebellion against Frieza. He failed and Frieza blew up their planet, believing he had rid the universe of saiyans.

Goku doesn’t know any of this. He’s a happy-go-lucky child. Dragon Ball, the first series, follows Goku as a naive, pure-hearted martial artist as he travels the world hunting for the seven dragon balls, which summon a serpentine dragon who will grant the person who finds them one wish. Villains in Dragon Ball typically seek to make themselves immortal. Goku just wants adventure and to protect his friends. Characters are able to fly, move at the speed of sound (or light), and fire energy (ki) blasts from their hands. Physical combat occurs on the ground and in the sky. Toriyama, in Japan, did not have to tone down violence for children: Dragon Ball fighters curse and bleed. Their enemies kill in cold blood, committing mass genocide against defenseless humans or horrifically draining them, one-by-one, of their internal organs. But Toriyama had a playful side, too. He loved toying with names—one cavalcade of Dragon Ball villains were named after instruments, including Piccolo, Tambourine, and Piano, and the saiyans had a vegetable theme, beginning with their king, Vegeta—and working gags into the manga and anime that would have been unsuitable for conventional American cartoons, like a perverted, elderly martial arts teacher (Master Roshi, another bit of wordplay, since “roshi” just means “master”) who lusts after younger women.

The heart of Dragon Ball Z is Goku’s adulthood. His saiyan brother arrives from space to menace Earth and steal the dragon balls. Goku, now with his young son Gohan, learns the truth of his past and joins up with an old enemy, Piccolo, to fight his brother off. Goku sacrifices himself, in a battle maneuver, to kill his brother and save the world. In the Dragon Ball universe, death is not taboo—it is, in fact, a part of life, except characters do, with the magic of the dragon balls, shuttle between an elaborate afterlife (the Other World) and the world of the living. Goku, in death, continues his martial arts training with a cooky spiritual deity, and is wished back to life to defend Earth again—this time against Vegeta, prince of the saiyans, who has come to Earth to steal the dragon balls and avenge the death of Goku’s brother, who was one of the last living saiyans.

I could numb you with plot summary. Instead, I’ll linger on what I found so compelling about Dragon Ball Z: character development. Few individuals in the Dragon Ball universe remained static. Consider Vegeta, my favorite. At the start of DBZ, he’s a sadistic, ruthless villain, the murderer of countless civilians on alien worlds. After his sidekick, Nappa, fails to defeat Goku, Vegeta pretends to help him up and instead flings him into the sky, killing him with an energy blast. It’s one of the more brutal scenes in the series. Ultimately, Goku is able to defeat Vegeta, and the saiyan prince, badly bloodied, retreats to space. But Vegeta and Goku cross paths again, and Vegeta slowly morphs from sadist to brooding antihero to, eventually, one of Earth’s defenders. He marries a human, Bulma, who is Goku’s oldest friend, and they have a son, Trunks. Vegeta obsesses over surpassing Goku and never quite can, despite his royal bloodline. It was Goku, for example, who first becomes the messianic super saiyan, an ultra-powerful golden-haired fighter. Rage powers the transformation and it took Frieza killing Goku’s best friend, Krillin, to unlock the once-in-a-millennium power. Goku’s transformation spurs Vegeta to train furiously and become the second super saiyan.

The genius of DBZ derived from the unexpected twists, evolutions, and regressions. Vegeta does not simply become good. Deep into the series, when he’s settled on Earth and raising a family, an evil warlock appears who is trying to free a magical, destructive entity named Majin Buu. The warlock tempts Vegeta, offering to make him all-powerful by releasing the darkness in his heart. Vegeta takes the deal because he still wants to surpass Goku, who has been allowed to return from the afterlife for a single day (Goku died a second time, sacrificing himself to save the Earth from the android Cell). Goku, naturally, does not want to fight Vegeta. To lure Goku into combat, Vegeta obliterates a stadium’s worth of people. Now branded with a black “M” on his forehead—for Majin—Vegeta gets his epic battle with Goku, his attempt, even with black magic, to prove himself worthy. Thanks to the energy released from their fight, Majin Buu, Dragon Ball Z’s last villain, awakens. Slowly, Vegeta understands just what he has done, since Majin Buu is far stronger than anyone on Earth, including him.

Here, the series reaches a level of pathos rarely seen in contemporary animation. Vainglorious, blood-thirsty Vegeta realizes how much suffering he has caused. He sees, too, there is only one way to try to stop Majin Buu. He goes to his son and holds him for the first time since he was a baby. When he knocks him out cold, along with Goku’s young son Goten, it still seems Vegeta is grappling with evil. But he has done this only so Piccolo, another fighter, can take the boys far away from the battlefield.

“You’ll die, you know that,” Piccolo tells Vegeta, who is about to face down Majin Buu alone.

Vegeta simply asks if he’ll meet Goku in the afterlife.

“I’m not going to lie to you, Vegeta, although the answer may be difficult for you to hear. This is the truth: Goku devoted his life to protecting the lives of others,” Piccolo replies. “You, on the other hand, have spent your life in pursuit of your own selfish desires, you’ve caused too much pain. When you die, you will not receive the same reward.”

Vegeta can only so smile.

“Oh well, so be it.”

Buu toddles closer and Piccolo flies away. Another hero, flying with Piccolo, calls Vegeta “crazy” and says Buu will easily destroy him. “For the first time,” Piccolo tells him, “Vegeta is fighting for someone other than himself, controlling his own fate.”

The episode ends with Vegeta, powered up one final time, exploding in a great ball of atomic light, immolating his own body so Buu can be destroyed.

Toriyama, of course, can’t leave it there. Vegeta’s sacrifice fails. He is dead and Buu, ever-demonic, resurrects himself.

No American show had ever seized me in such a way. The Joker could not reform himself, marry a woman in Gotham City, fight alongside Batman, give in to temptation and try to kill Batman again, and later, when confronted with an even stronger villain, blow himself up to save his family and Gotham. Toriyama simply dreamed of narrative differently. He was an original, and his creations will long outlive him; Dragon Ball retains its remarkable global reach, with fans in South America, Asia, and the U.S. consuming new series with equal fervor. DBZ spawned GT and now Super. There are always new movies. I’m no longer a die-hard, but I still, years after my Dragon Ball heyday, worked in an oblique reference to Vegeta killing an android in my first novel. No matter how long ago it was when I first bought those VHS tapes, the otherworldly adventures Goku and friends will loom large in my mind. For that, I have Toriyama to thank.

It's wonderful to read such a detailed explanation of how consciousness develops from childhood. It almost (but not quite) makes me want to watch these things. My formative consciousness builder was a French children's book written in the 1950's, Tistou of the Green Thumbs, by Maurice Druon. If you can find a copy, I highly recommend it.

It would not be overstatement to say that DBZ was my childhood. Great piece Ross!