"Weapons" and the Long Tail of Covid

A dark allegory in a hit new film

A new horror film is enrapturing America, and it’s well-worth your time. Weapons tells the story of seventeen schoolchildren who all disappear in the early morning and aren’t heard from again. They belong to the same classroom in a small Pennsylvania town and their young teacher is initially blamed for their absence. The film lingers on the teacher, a recovering alcoholic who rekindles her affair with a bumbling local cop, but it wisely takes in the scope of the whole town: we meet a flustered principal, a homeless junkie, an aggrieved father of one of the missing children, and, finally, the one boy who remained in the teacher’s class and will be the key to unraveling the mystery. The structure calls to mind, for me at least, Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio, which derives its power from that sort of human sweep: a town is an organism and its cells, growing and dying, are its people. Weapons, gory and horrifying and often funny, doesn’t lose sight of this.

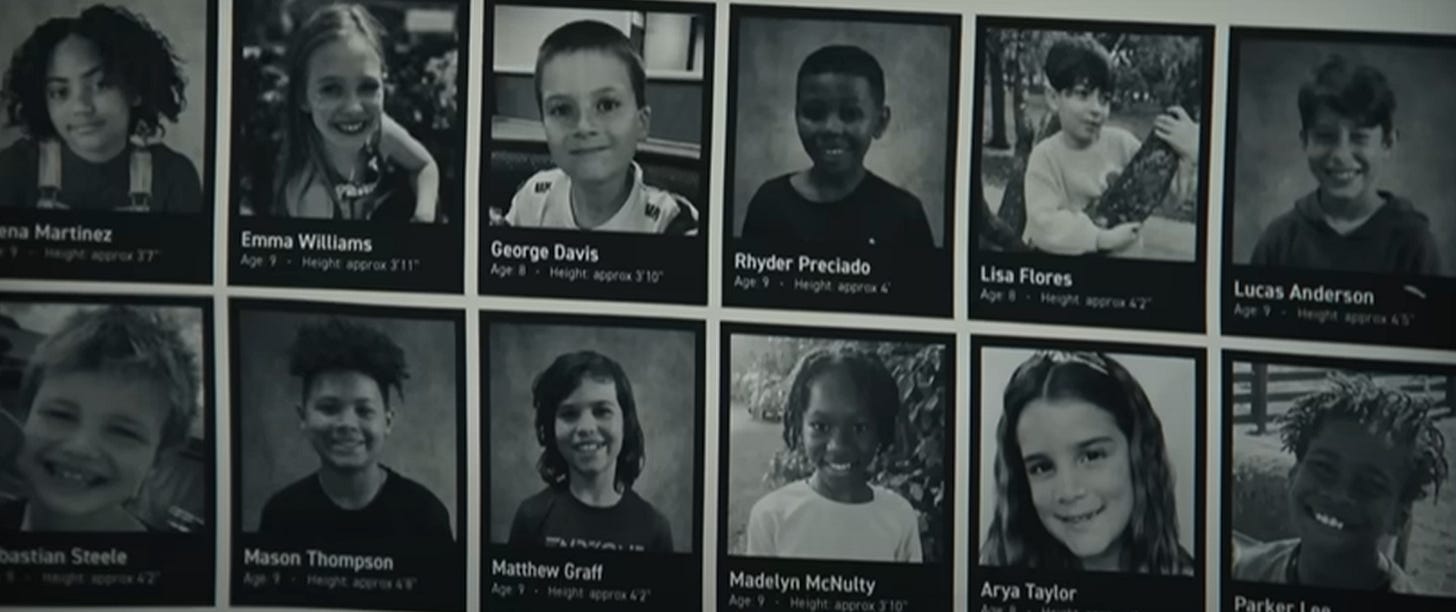

There’s been much debate over what it all might mean, and here is where, to discuss the film further, I will need to spoil it for you. If you don’t want to know anymore, abandon this essay. The children disappear because they are being held captive in the house of the only student who remained in class, Alex. Alex’s parents have a “great aunt” named Gladys who turns out, unbeknownst to them, to be a witch. Gladys is very old and sickly, and Alex’s mother explains that they are caring for her because she has nowhere else to go. But Gladys has other plans: wielding her dark magic, she drains Alex’s parents of their life force. They remain alive, in a kind of suspended animation, and Alex must feed them cold soup to keep them from starving. Alex’s parents, though, don’t provide enough energy for Gladys to survive and thrive. When Alex mentions his classmates to her, Gladys tells Alex to retrieve objects from his classroom and bring them to her. Objects in hand, she uses her magic to summon the kids in the early morning to the house, where they’re herded into the basement and harvested for their energy. Gladys, in turn, gains strength, and she spends the rest of the film—it has a fantastically bloody conclusion—staving off the townspeople, who are naturally desperate to find the children.

What is the allegory? Zach Cregger, the writer and director, has remained coy, allowing others to interpret his film for him. It’s refreshing that the moral is not straightforward, that Cregger is daring his audience to wrestle with ambiguity. The 2010s-style signpost era, when a director would hammer the viewer with a party line or make an implicit demand of them, is coming to a close. The two most popular interpretations of Weapons revolve around school shootings and Covid, though neither of these seem particularly right to me. Or, I should emphasize, the Covid allegory isn’t complete. It’s easy enough to see why these two interpretations, one left-coded and one vaguely of the right, have taken hold. In the film, the school is closed for a month after the disappearance of the children. The children who haven’t vanished are kept home as the investigation continues. When the administration realizes the school cannot be shut down indefinitely, the teachers and students return. And then, later on, one of the parents of the missing children has a dream of an AR-15 materializing above the town. The children, gone from the classroom, are like those, perhaps, who have been slaughtered in Sandy Hook or Uvalde. Of course, the children of Weapons aren’t actually dead, merely missing, and the school shooting allegory doesn’t go far beyond that dream. The commentary on Covid era closures, if understandable, doesn’t penetrate deeply because school is in session for the vast majority of the film. This isn’t a story about children staying home. We see packed classrooms, packed auditoriums, and a beleaguered public school administration grappling with a tragedy no one can explain.

But a darker current related to Covid does pulse in the film. John Pistelli, the novelist and critic, landed on it first, and he explains it well. “Critics have decided to talk about everything else—it’s about alcoholism! it’s about gun control! it’s about consumerism! it’s about fungus!—but no, it’s about a sick old woman who sacrifices a group of schoolchildren for her health, only to see those youth rise up and tear her limb from limb,” Pistelli wrote. If, he added, “a horror movie doesn’t convey an underlying unconscious unwholesome fantasy, it will be ignored and forgotten: horror movies are what Freud thought dreams were … the sparagmos of the witch, the youth-revolt slaughter of the elderly parasite, the disarticulation of a social order coded as both a gynocracy and gerontocracy. Ugly story, amusingly told.” Conscious or not, this is the vision Cregger brings to the screen, and it’s one derived from the sideways spirit of our age. The pandemic itself, hitting in 2020, was initially a collectivist enterprise, many of us staying home to save lives. (The working-class and poor, unable to default to the laptop screen, could not cocoon themselves.) If we did this long enough—to some indeterminate future point—we’d flatten the curve and get 2019 back. While lockdowns could be more successful than right-wing critics would admit, they were not sustainable. As the pandemic dragged on, the scientific establishment, along with a large number of politicians, would argue for indefinite closures as a means of protecting the elderly and the immunocompromised. Unlike the pandemic of a century ago, this one ravaged the old far more than the young: the single greatest comorbidity was age, followed by underlying health challenges like obesity. In the pandemic’s second year, as vaccines were rolled out and lockdowns were lifted in some states and sporadically reimposed in others, the new fault line became the vaccine itself. The scientific establishment argued for an all-of-the-above strategy, injecting healthy children and young adults at the same rate as seniors—we’re all in this together, remember—even though the vaccines were produced in an incredibly short timeframe and would, as even venerable liberal news outlets would later concede, occasionally cause severe injuries. For the elderly, taking on the risk of a very new, Trump-produced vaccine made sense because Covid was such a grave threat to them. But why force a perfectly healthy 29-year-old to receive a Covid vaccine? The argument, proved to be faulty as Covid inevitably evolved, was that the vaccinated could not spread the virus so readily. The emergence of the delta and omicron variants put that bit of fake news to bed. By now, with the vaccinated still catching and passing on Covid, no one can seriously argue the vaccine stopped the spread of the virus. What it did do was present the worst health outcomes; it was always vital for the elderly and immunocompromised to receive their updated Covid vaccines. For the rest of the population, though, the arguments for Pfizer’s wares were much more specious. Young and healthy people did get sick and die from Covid, but many more batted it away easily enough and could have lived, by 2021, with a great degree of normalcy.

Yet it took years for that normalcy to arrive. In 2021, I encountered a strong amount of resistance when I critiqued, in a national magazine, the efficacy of vaccine mandates and passports. It is easy to forget now, but it was literally against the law in certain cities, if you did not receive the Covid vaccine, to enter a restaurant, a movie theater, or other public indoor spaces. The unvaccinated were fired, en masse, from their public sector jobs, even though they theoretically enjoyed the protections of a union. Private sector employers, under pressure from the government, mandated vaccines for most kinds of work, creating a two-tiered system that locked many Americans out of the job market altogether. The science behind all of this was dubious at best and idiotic at worse. Democrats do not want to admit this, but their party suffered deep damage from this phase of the pandemic that they, to this day, have not truly recovered from. If Cregger had no intention of nodding to this era, he will have, like a good Freudian, perhaps inhaled the remnants unconsciously. In Gladys, we behold it all.

The pandemic was devastating for the elderly because they were most likely to die. But it punished the surviving youth in a manner that was especially cruel, given that, for all the technological advances we’ve made as a species, we’ve found no way to recover time. A generation of teenagers and twentysomethings were denied their high school graduations, college graduations, and proms. They lost out on in-person work and in-person play. Pivotal years of development were washed away. A middle-aged or elderly individual, isolated during Covid, could at least look back on a life well-lived, the many years they had relished before isolation arrived. But the youth had no such consolation, and they were expected to sacrifice what they did have for a goal that was nebulous and made less sense as the months leaked away. On a greater scale, they beheld the gerontocracy itself: the aged who had accrued vastly more wealth and political power, who lived in the White House and dominated Hollywood and owned much of the land beneath them. Joe Biden, at age eighty-one, demanded his second term, and would have stumbled deep into the general election had he not possessed the Lear-like hubris to debate Trump at the start of summer. Trump, of course, is a Baby Boomer himself, and will have been something of an eternal president to these beleaguered youth, spending more than a decade at the center of the public consciousness by the time his second term is through. In the 1960s, a youth revolt—the power was in the numbers, the sheer amount of human beings born between the years 1945 and 1955—seized the culture and vaulted it forward. Now we find stagnation, with this same cohort, in their retirement years, still standing at the summit. The youth, in Weapons, slay their ancient tormentor, but they are not exactly free—many remain catatonic, and the narrator implies some, as time passes, will regain a semblance of their old selves. The damage, in one sense, is done, just as the scars from the pandemic still linger, even if we now mostly ignore them. Gladys, in Weapons, might be gone, but we are left to wonder what it meant for these children to disappear in the first place and have their bodies harvested. This is not an allegory most filmgoers want to mull for too long. It is more politically fraught than gun violence, a red versus blue clash in which the latter occupies the moral high ground. (No other advanced nation on Earth tolerates firearms like the United States.) It unsettles far more than the old battles over school closures; there has been a detente reached between red and blue, with the latter tacitly acknowledging they overreached and everyone agreeing, in 2025, flesh-and-blood schooling is absolutely necessary. The remote experiment was a failure. But it’s taboo, still, to reflect on the tradeoffs made in the name of science, the civil liberties so easily wiped away and a generational tug-of-war that robbed, temporarily at least, the adolescents and young adults of their milestones. We are now in a post-pandemic world and it is hard to know, if another deadly virus comes, how we as a society will react. Would we be any better off? What will we have learned? How will politics bend us? These are questions, we hope, we will never have to answer.

I don’t buy your argument that the science behind healthy younger people getting vaccinated was faulty. For one, myocarditis was more likely to be the result of getting covid than from getting the vaccine. As for its effect on spread:

Early (Alpha/Delta) data showed vaccinated people were less likely to get infected and to pass it on in households. With Omicron, protection against infection and onward transmission dropped and waned faster, though there’s still a measurable reduction for a few months after a recent dose. For example, one California prisons analysis estimated ~30% indirect protection against Omicron transmission within 3 months of vaccination.

It wasn’t “fake news” that the vaccinated couldn’t spread the virus as easily prior to the emergence of the delta and omicron variants — it was a reasonable position based on what was known at the time. A lot of these kinds of criticisms of the COVID response rely a lot on hindsight bias.