We're Still Waiting for the Eric Adams Agenda

Day One is Almost Here

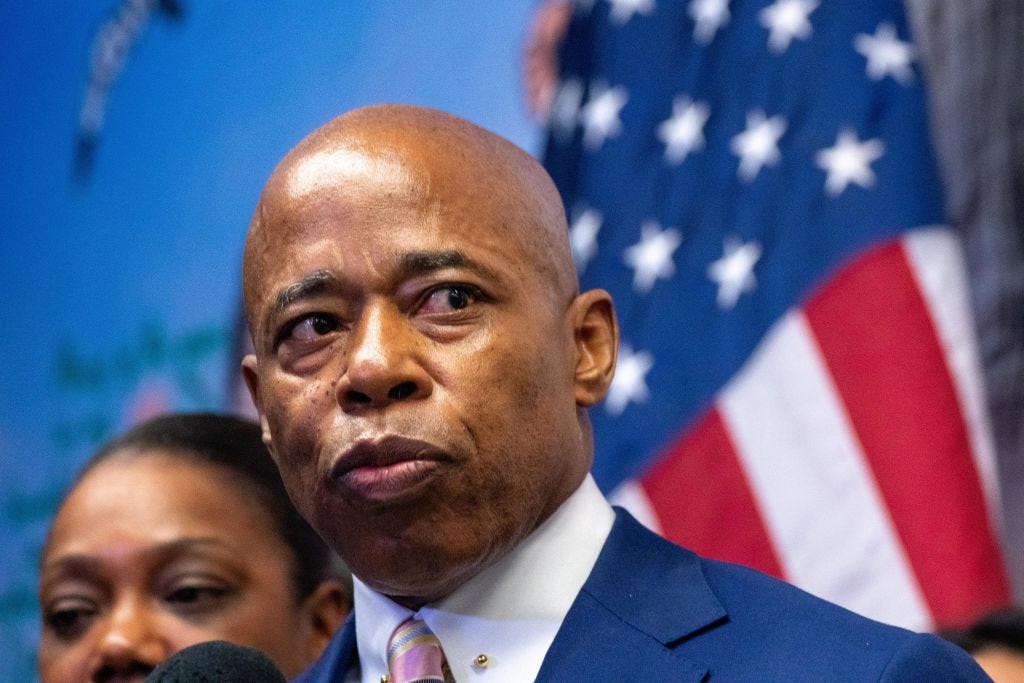

In a few days, Eric Adams will be the mayor of New York City. Omicron’s rapid spread may have dampened the usual enthusiasm and attention to this transition, but it remains momentous. Soon Adams, the outgoing Brooklyn borough president, will have one of the most important and challenging jobs in America.

Adams has already announced a slew of hires: five deputy mayors, all women, along with a police commissioner, a schools chancellor, a corrections commissioner, and a transportation commissioner. He has held a series of press conferences to introduce some of the new leaders to the public. A communications director, who is a Schumer veteran, is joining his team too.

A former police captain, Adams spent much of his time on the campaign trail talking about how he’d drive down the number of shootings and murders in New York City following the pandemic-era spike. He has called himself the “face” of the Democratic Party and taunted its left flank. Unlike Bill de Blasio, he has openly embraced the business community, promising some kind of return to the Bloomberg era, though that remains thinly-sketched. Most of his incoming deputy mayors and agency heads are veterans of the de Blasio and Bloomberg administrations, promising some synergy of the two worlds.

I am still waiting to see what this all adds up to. In the next print issue of the Nation, I wrestle with this question a bit more and I still don’t have a great answer for you. It remains entirely unclear what Adams wants to do on day five, day fifty, or day one hundred of his term. There is no defined agenda waiting—or if there is, he hasn’t told us about it.

Instead, the Adams City Hall seems to be pursuing issues on a case-by-case basis, treating news cycles as opportunities to flush out positions. One week, he cared a lot about cryptocurrency. Lately, he has said he would reinstate the practice of solitary confinement on Rikers Island—or, as it is technically called, punitive segregation. The replacement policy the de Blasio administration has enacted, known as the Risk Management Accountability System—it is supposed to give inmates at least ten hours outside their holding a cell a day—does not fit the United Nations’ Mandela Rules for the minimum treatment of prisoners’ definition of solitary confinement: 22 hours or more a day without “meaningful human contact.”

The move to bring back solitary confinement, defying a majority of the City Council which has called on him to not reinstate the practice, comes after he suffered his first political loss. Despite Adams heavily backing Francisco Moya, a candidate for City Council speaker with little organic support, labor unions and a large number of council members overrode the mayor-to-be, choosing another moderate, Adrienne Adams. Adrienne Adams, of no relation to Eric Adams, is not ideologically opposed to the new mayor, but she is likely to face pressure from the body’s left flank to be independent of him whenever possible. The office of council speaker, due to term-limits—the last two speakers presided over the body for four years —continues to weaken, with individual members gaining more and more clout over legislation and committee assignments. What is still to be determined is what the Eric Adams legislative agenda actually is, what he’ll try to force through the Council or cajole members into supporting. He has not touted a list of bills or talked of any in particular.

The same applies to Albany. Adams made much noise over the last few months over mounting some sort of campaign in the Democrat-run state legislature to weaken the historic criminal justice reform laws passed in 2019. Sensing, eventually, Senate and Assembly Democrats had no intention of enacting the changes he sought, Adams announced he would instead appoint the “right” judges in Criminal Court that would make sure “those who pose an imminent threat to my city” stay off city streets. Fair enough, but that’s not a legislative agenda. Instead, Adams has taken positions in piecemeal.

All of this is a stark contrast to the month leading into Bill de Blasio’s mayoralty. Much-maligned these days, de Blasio was a deceptively accomplished mayor who had a defined legislative agenda for his first year in office. He wanted to go to Albany to demand a tax hike to fund his new universal pre-K program. He wanted to sign into law a long-halted bill that would guarantee paid sick days for all city workers. He wanted to stack the Rent Guidelines Board with tenant-friendly appointees. He wanted to bring a municipal ID to New York City. At no point was there a question of what de Blasio wanted to do—you either agreed with him or didn’t.

The possibilities for an Adams administration are boundless. He might end up, as a blend of Koch and Dinkins and Giuliani and Bloomberg and de Blasio, a startlingly successful mayor, drawing from the best of all these men. He might be a disaster. He may land somewhere in between. These are banal predictions, to some extent, but they’re all we have.

One danger Adams will face is treating City Hall like another Borough Hall. This does not just mean his penchant for soft corruption—there will be plenty of that to go around—but governing in a reactive and impulsive manner. Like de Blasio, Adams will become mayor after holding a largely ceremonial post. The borough president’s office has little formal power and exists, these days, as a place to stuff patronage and burnish political careers. As borough president, Adams mostly chased news cycles, fulminating about rats or fast food or whatever, on a particular day, struck his fancy. Over eight years, it was hard to find a defined message, policy agenda, or particular project Adams applied his bully pulpit toward for an extended period of time. In the mayoral election, he leaned into his experience as a former police captain, bypassing his time in the borough presidency and the State Senate to speak directly to voters on the issue of crime. He read the electorate well and was rewarded with a narrow victory.

Now he will have to do much more. Bloomberg and de Blasio each had visions for how they would guide New York through the twenty-first century. Adams has, so far, offered little comparative sweep. There is still time to do so. Reeling, once more, from the pandemic, the city needs a leader to inspire, to point the way forward to a greater future. What projects will he champion? What legislation? What will he leave New Yorkers with?

DeB had a detailed sweeping progressive agenda and a list of impressive achievements, and extremely low approval ratings. Constantly pilloried by the NY Post and progressives, he leaves office with no political future and looked upon by voters as a failed mayor.

Do newly elected mayors need sweeping agendas? No one has answers for crime or homelessness, every city from mid sized to large grapple without much success. We know numbers of police have little impact, harsh policing, longer sentences, going back to the Guiliani days satisfies the Post and angers the Council.

A 9% unemployment rate is both disastrous and is not decreasing.

Perhaps a mayor as fireman putting out fires will satisfy the populace more than sweeping policies- an anti deB

You are one good reporter/ journalist.