What Can Actually Fix the Media?

The bloodletting continues

Every year since I entered the media industry, there have been layoffs. I can’t recall, in my working life, a “good” year for the media. This is, in part, a function of my age. I became a journalist when I was twenty-one in 2011, just three years after the economic crash. Newspapers were collapsing all around me. Digital start-ups seemed to offer a brief reprieve, but smarter people sniffed something of a con—for most of them, there was no serious business model. Investors wanted growth and believed, somehow, the money would follow later. BuzzFeed, emblematic of this era, never had a paywall or a subscription model. It never made itself worthy of one. Predictably, it foundered, and its old editor-in-chief, Ben Smith, is hoping to learn from his mistakes with his latest venture, Semafor. At some point, Semafor will have to start charging users for the privilege of its journalism.

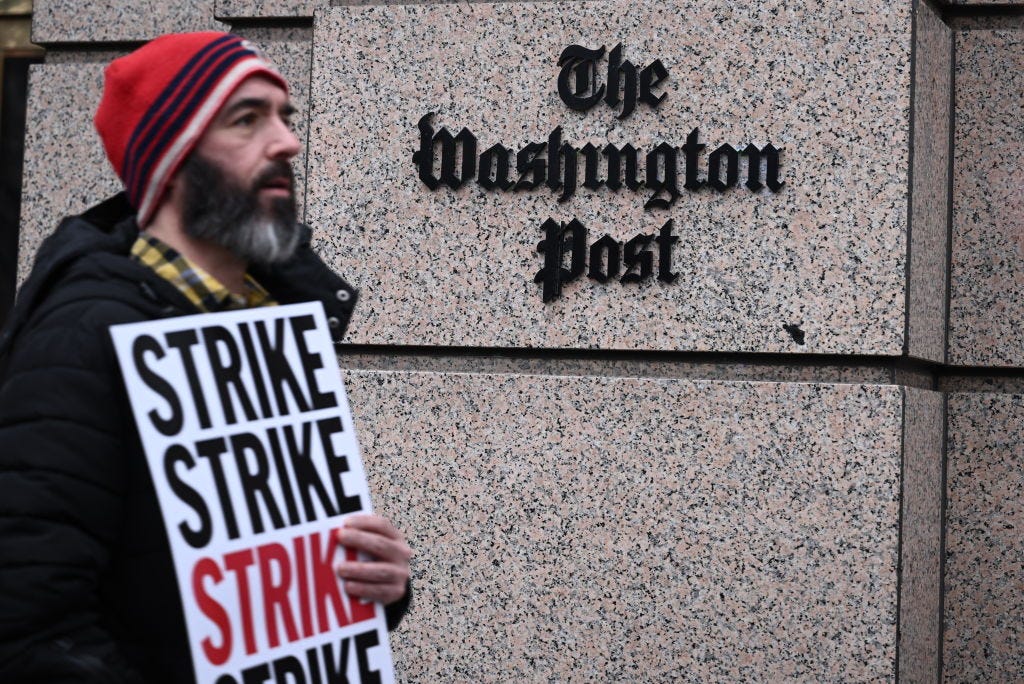

This past year has not been worse than 2009 or 2010 or 2011, but it has been bleak. The relaunched Gawker shut down, Condé Nast laid off staff and made cuts at the venerable New Yorker, NPR cut ten percent of its workforce, and Vox Media laid off four percent of its staff last month. The Washington Post is contracting as Jeff Bezos seems to tire of overseeing a money-losing operation. Meanwhile, local newspapers across America continue to shut down. News deserts are everywhere. By next year, one-third of the newspapers that existed in 2005 will have vanished. This is the actual crisis of American democracy. It exceeds any posed by another Donald Trump presidency.

Why is this happening? It’s an old story. The internet ravaged the print advertising market and blew up the bundle. At one time, to find out the weather or the movie times or the box score or do the crossword or rent an apartment, you had to buy a newspaper. All of this underwrote the accountability journalism that was vital for democracy but could never, on its own, pay the bills. Craigslist killed the classifieds section, but if Craig Newmark hadn’t done it, someone else would have. Newspaper conglomerates adapted very poorly to the 2000s era internet. They decided it was a good idea to take all the paid content in their newspapers and give it away for free online. The Times was smart enough, in 2011, to institute a paywall, but it was too late for most others. Newspapers also found the digital ad market was nowhere near as robust as its twentieth century print equivalent. Digital ads commanded pennies on the dollar of an old print ad. Soon, Facebook and Google were swallowing up most of the revenue anyway because they were far better at microtargeting consumers. Since they had hoovered up so much their data, selling products to them wouldn’t be too hard.

The news industry never recovered from any of this. It has gotten so bad that there is now a market inefficiency to be exploited for local news. As Matt Yglesias pointed out, so little local coverage now exists, a publication that did something straightforward like write much more about D.C. crime and local public schools than the state of Congress could probably scoop up paid subscribers. Yglesias also argues for less opinionated news reporting, which is a decent business proposition in an era of hot takes and supposed moral clarity.

But the problems are bigger, of course. Newspapers lose money, online startups lose money, and nonprofits hang on for dear life.

What can actually be done? How can all of this be fixed?