When a Major Political Candidate Took on the PBA and Won.

Remembering Ed Koch's 1977 mayoral campaign, which put attacks on police unions front and center.

Next year, New York City will be treated to another wide open mayoral race. No one knows what will happen or how it will be waged, with the possibility of coronavirus still looming. Mayoral races can be raucous, festive affairs, even in times of crisis—candidates stump in crowded subway stations, street fairs, beaches, housing complexes, and even meat lockers. My introduction to real municipal politics was the 2013 mayoral race, a zany contest best remembered as the staging ground for Anthony Weiner’s comeback attempt and second, of many, sexting scandals. That summer, I chased around all the candidates, spending inordinate amounts of time with Weiner, Bill Thompson, John Liu, Christine Quinn, and the long-shot, Bill de Blasio. There were times I was the lone reporter with a candidate, since they were so many events. No one wanted to sweat it out with de Blasio in a Bay Ridge subway station on a random July day. After the implosion of Weiner’s campaign, it was only Jacob Kornbluh and I who followed him out to a pre-Passover tour of Borough Park storefronts, where the former congressman engaged in a shouting match with a patron that went viral and later made the documentary. I also chased around a former governor named Eliot Spitzer who was, to everyone’s shock, running for city comptroller. Truthfully, there wasn’t a better way for a 23-year-old reporter to spend the summer. To this day, I don’t think I’ve ever enjoyed an assignment so much.

The 2013 election season, in retrospect, may have been the second-most fascinating of the last 50 years in New York. What still topped it all was 1977, when a host of high profile Democrats piled on Mayor Abe Beame, who was reeling from the city’s fiscal crisis and rising crime. Mario Cuomo, the future governor of New York, took on Beame, with a problematic son named Andrew helping to head up the campaign efforts. Former Congresswoman Bella Abzug, the feminist icon and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of her era, entered the race after narrowly losing a bid for the Senate. Percy Sutton, the Manhattan borough president, sought to become New York’s first Black mayor. Herman Badillo, the first Puerto Rican to serve in the House and the former Bronx borough president, was in the race, attempting to make history as the city’s first Hispanic mayor. Rounding out the field was a Manhattan congressman named Ed Koch who was punchy and colorful, but not expected to win.

The backdrop of the race was utter chaos: the 1977 blackout, which resulted in looting that far surpassed any seen this spring, and the Son of Sam murders. Buildings in poor neighborhoods were set ablaze for insurance money. Roger Starr, an influential urban planning voice of the era, advocated for starving low income neighborhoods of resources. It was a grim time and Koch, once a reform-oriented liberal, read the electorate very well. Those out of work or underpaid were growing resentful of New York’s powerful municipal unions. Outer borough white backlash was underway against the city’s social services, which were a particular lifeline for Black and Puerto Rican residents. (The term Latino was not yet in vogue; almost all Spanish-speaking New Yorkers of this time were from Puerto Rico.) Koch set out to carve a path in the Democratic primary as a “liberal with sanity” who would challenge traditional Democratic interest groups, like organized labor. Though he didn’t identify with the term at the time, Koch campaigned as a Third Way Democrat; leaders like Bill Clinton would rise to prominence a decade later, arguing for an embrace of big business and a rejection of the New Deal legacy.

It was a savvy decision for Koch, who had come up as a Greenwich Village liberal in the anti-Tammany Hall movement. The Democratic electorate, viewing the John Lindsay brand of social liberalism with growing disdain and regarding Beame as an ineffectual New Dealer—Beame did not want to accept the devastating austerity measures imposed by the banks and federal government—increasingly turned to Koch, who had a message distinct from Cuomo and Abzug, his two most prominent rivals outside of Beame. In blunt television advertisements, Koch took direct aim at municipal unions, portraying himself as a tough-talking outsider who would stand up to them on behalf of non-unionized New York. In addition, Koch ran on an aggressive law and order message not so different than what we hear today from Donald Trump. He repeatedly called for the death penalty to be legalized in New York, though it was a state issue, not a municipal one. In a high crime era, Koch’s promise to increase arrests and ultimately kill more people resonated.

One surprising element, at least from a historical perspective, was Koch’s campaign against the Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association, the city’s most prominent police union. As I reported for the Nation, the PBA and other police unions have been a roadblock to reform for a half century, in part because politicians were afraid to challenge them. With crime on the rise, police unions could threaten politicians with slow downs or strikes if they pursued reform policies, potentially triggering increases in violence. Democrats and Republicans who wanted to campaign on tough-on-crime platforms inevitably courted and defended police unions.

Koch, though, was up to something different.

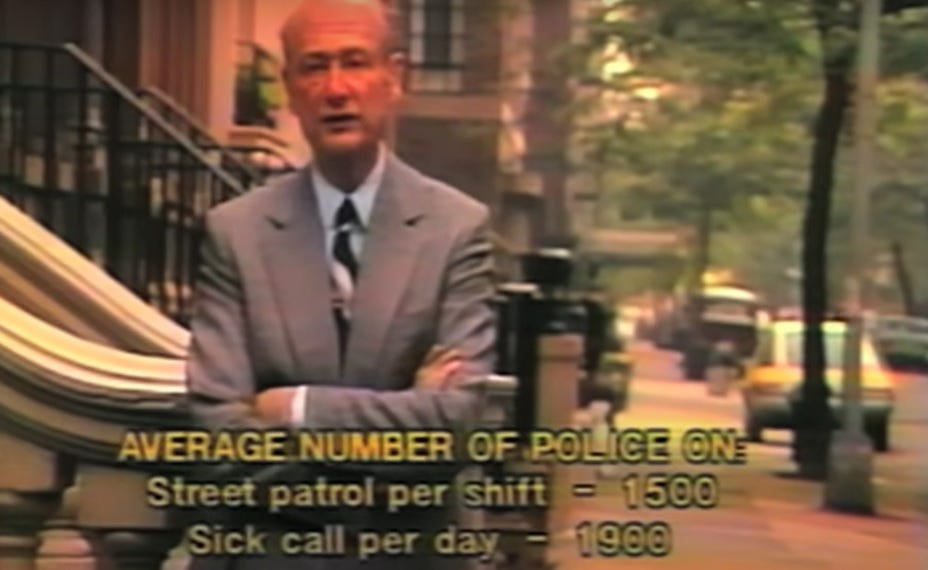

“We pay the average police officer $30,000 a year in salary and benefits to protect us,” Koch said in one TV ad, trying to underscore how well-compensated cops were by the standard of the 1970s. “But of 25,000 police in the city, only 1,500 patrol the street on an average shift. More cops than that call in sick every day. Obviously we need more police on the streets and we can do it without spending more money by better use of the police force we already have. That may mean taking on the police bureaucracy and the PBA but that’s what a mayor has to do.”

Even Bill de Blasio, campaigning on a platform to overhaul the police in 2013, didn’t dare say in a television advertisement—or anywhere, really—that he’d “take on” the PBA. But it was message Koch returned to, again and again. “Mr. Mario Cuomo is catering to Sam DeMilia — the same Sam DeMilia who asked police officers not to volunteer to work on the ‘Son of Sam’ case on their own time,” Koch said that September, referring to the president of the PBA at the time. “Mr. Mario Cuomo did not have the courage to say to Sam DeMilia that that was terrible thing to say.”

“I“m not afraid to take on Sam DeMilia,” Koch added.

Koch blamed the PBA, like other municipal unions, for almost bankrupting the city. "The union requires the city to give cops two days off if they give blood,” Koch liked to say on the trail. When Koch gave blood, rather, he’d “grab a cup of coffee.”

Koch’s calculation was that the people who wanted more police on the streets had no particular loyalty to organized labor. The outcome of the election would prove him right: he narrowly finished ahead of the field in the September primary and bested Cuomo in a bitter runoff. Cuomo, remarkably, didn’t even concede then, racking up 41 percent of the vote on the Liberal Party line that November. Ed Koch was elected mayor.

Koch would not be a mayor in opposition to the PBA. Rank-and-file cops, like most white working class voters, embraced Koch and the police unions followed suit. He had no great interest in overhauling an insular police department beset by allegations of corruption and brutality. It would be the man who defeated him, David Dinkins, who would successfully introduce civilian oversight of the NYPD.

In 1989, as Koch was seeking a fourth term and trying to fend off Dinkins, the PBA proudly endorsed him.

'“No one, no mayor in recent history, has been more supportive of police officers,'' said Phil Caruso, the PBA president. ''No one has been more aggressive in terms of law enforcement on all the issues - drugs, the death penalty and putting more police officers on patrol.”

Caruso was asked at the press conference why the PBA was endorsing Koch and not the Republican prosecutor gearing up for the fall campaign, Rudy Giuliani. “We have been consistent supporters of Mayor Koch because he has been supportive of us,” he said.

Though his mayoralty had fulfilled certain progressive aims, like building far more affordable housing, Koch was never going to give ground on any issues pertaining to criminal justice. Once out of office, the former mayor would only drift further to the right, backing George W. Bush for president after the invasion of Iraq.

By the 1980s, he had left his liberal past long behind.

“You stand between us and the murderers and the rapists and the assaulters,” Koch said to the PBA. “You are that thin blue line.”

'Once out of office, the former mayor would only drift further to the right, backing George W. Bush for president after the invasion of Iraq. '

He took this to his grave, too, making himself out to be a martyr in the vein of Daniel Pearl. A noxious thing.