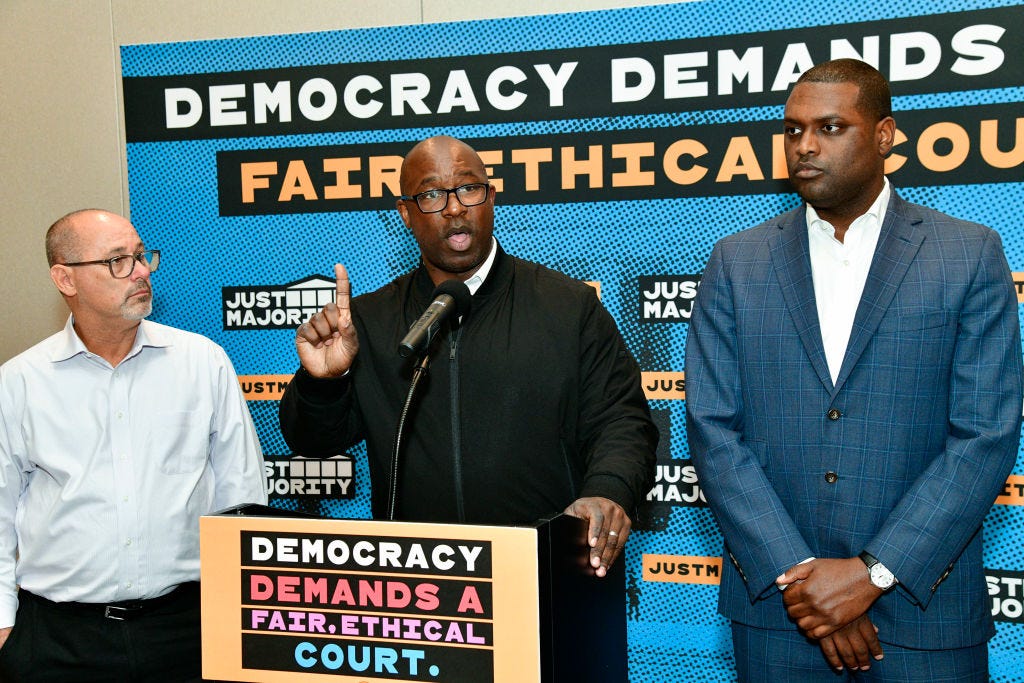

Who Is Mondaire Jones?

A young Democrat sprints to the center

In 2020, Mondaire Jones was open to defunding the police. He was a supporter of Medicare for All. He proudly touted Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s Green New Deal.

Back then, he was competing in an open Democratic primary for Nita Lowey’s old House seat north of New York City. He was a 33-year-old Harvard Law graduate who spoke like a member of the Squad, if he never joined the leftist group in Congress. He was, at the minimum, very popular with progressive activists, and when he won the primary overwhelmingly, he was immediately tagged as a rising star within the Democratic Party. Along with Ritchie Torres of the Bronx, he made history as an openly gay and Black member of Congress. He was also, like another progressive just south of him, the first Black man to represent his district.

Jones and Jamaal Bowman, the Westchester congressman, were allies during their one term in Congress. Bowman was more proudly of the left, embracing the Democratic Socialists of America, but they were aligned on most issues and committed to pushing the new Biden administration leftward. Jones, in particular, had made it his cause to expand the Supreme Court so liberal judges could outvote the conservative majority. Both men, on foreign policy, even drew close to J Street, the liberal counter to AIPAC in Congress.

All of that has now changed. Earlier this week, Jones shocked progressives by endorsing George Latimer, the more moderate Westchester county executive running to oust Bowman from Congress. In his statement, Jones said he was making the endorsement because Bowman was too anti-Israel. “I have been horrified by his recent acceptance of the DSA endorsement, his denial of the sexual assault of Israeli women by Hamas on October 7, and his embrace of Norman Finkelstein, a well-known antisemite.”

How did Jones go from being a Bowman-friendly member of Congress to a candidate for office now endorsing an insurgent beyond his district against Bowman? For all the agita Bowman has generated among Israel hawks and his flirtation with anti-Zionism, he still has the backing of Hakeem Jeffries, the House minority leader and a staunch Israel supporter. Bowman, as a Black member of Congress, has also retained some backing from the local and national Black political establishment, since Latimer is white and the optics of the primary have made some uncomfortable. Jones has long been an identity-focused politician; the 2020 version of himself would never have supported a white moderate challenging a Black progressive incumbent.

Jones is no longer in Congress. He’s trying to get back there by running against a one-term Republican, Mike Lawler, in a Westchester and Rockland County-based district that Biden carried by around 10 points in 2020. Rockland has a large Hasidic Jewish population that has swung hard to the right and the district, overall, has a Jewish vote that Jones doesn’t want to lose completely. The endorsement of Latimer, in every sense, is a political calculation. Jones wants to declare his independence from progressives to appeal to moderates and swing voters. He also senses Bowman is vulnerable and might lose, which lowers the risk of being on the wrong end of endorsing a non-incumbent. This sort of left-punching may prove a winning a strategy. In the meantime, the progressive Working Families Party, which has endorsed both Bowman and Jones, has been put in a bind. “We don’t give the endorsement much weight. Voters know Jamaal has been one of the strongest champions in Congress for our public schools and climate,” state WFP spokesperson Ravi Mangla told Politico.

It’s not uncommon for politicians like Jones to pivot from the left to the center, especially as the political climate shifts. Performative leftism of the like Jones indulged in throughout 2020 and 2022 is not quite in vogue anymore, and it’s especially tough in a district with plenty of Republicans and centrist Democrats. What does set Jones apart, though, is the speed of his ideological shift and his overall political journey over the last two years. Close watchers of New York politics might remember that Jones, in the spring of 2022, was briefly a progressive martyr. A chaotic round of redistricting had left him with few good options for his re-election bid. The easiest option, a new district similar to his own, was suddenly seized by another Democratic incumbent, Sean Patrick Maloney. Maloney, ironically, was the sort of politician Jones has evolved into today: a left-puncher. He had been a close ally of Andrew Cuomo, the disgraced former governor, and delighted in attacking the progressive wing of his party. Left-leaning activists in Rockland and Westchester were appalled that Maloney had strongarmed Jones and even hoped Jones would run in a primary against him. Jones seemed to consider it, but backed away because Maloney, at the time, was a Democrat with seniority and a far larger war chest. Another progressive, Alessandra Biaggi, ran against Maloney and lost. Jones likely foresaw a similar fate for himself.

Foregoing the Biaggi path, Jones moved to Brooklyn. Redistricting had created a new seat in lower Manhattan and parts of Brooklyn. Many Democrats piled in, hoping for a shot at some D.C. prestige. Jones was the only candidate who, quite literally, had no connection to the area. The best he could muster was that he was gay and the new district, the 10th, included the site of the Stonewall uprising. It was a peculiar primary season; Bill de Blasio, the former mayor, was briefly a candidate, and Elizabeth Holtzman, the 81-year-old former congresswoman, entered the race as well. Jones, though, stood out for lacking any real campaign rationale. He was there because he lost his district north of New York City and wanted to stay in Congress. Every other top candidate had deep roots in Brooklyn or Manhattan. To make matters more vexing for the left, Jones was campaigning as a proud progressive in a winner-take-all primary that had morphed, rather quickly, into an ideological proxy war. Dan Goldman, a wealthy attorney, had gained fame for working on the first Trump impeachment but profiled more as a corporate, center-left Democrat, aligned with the real estate industry and law enforcement. His top rival was Yuh-Line Niou, a state assemblywoman with deep ties to the WFP and other progressive organizations. Niou had obvious flaws as a candidate, but she had a path to victory and likely would have joined the Squad if she had won. As election day neared, the primary evolved into a two-horse contest between Niou and Goldman, who was partially self-funding his bid. There were other viable contenders, including Carlina Rivera, a Manhattan city councilwoman, but it was those two Democrats who had the best chance to capture the nomination.

And then there was Jones. He was not talking to many media outlets but he was spending money and trying to win. When the dust settled, he had finished third with 18% of the vote. Niou was second, with about 24%. Goldman was the winner, with 26%, besting Niou by less than 2,000 votes. Did Jones cost Niou the election? There’s an argument to be made he did. Jones ran strongest in Park Slope, Gowanus, and Prospect Heights, affluent liberal bastions where Niou had won outright. There is no way to truly know, to figure out how many Democrats who voted for Jones may have opted for Niou if he hadn’t run. There were other candidates who could have eaten up that vote, including Jo Anne Simon, an assemblywoman from downtown Brooklyn, and Rivera. Jones did hoover up cash and attention from progressive-friendly donors and activists. If Jones had remained in Rockland and Westchester, Niou would have, at the minimum, benefited.

To recap: Jones was a Squad-friendly Westchester progressive in 2020, an aspiring Brooklyn progressive in 2022, and is now, in 2024, a swing district candidate who is actively endorsing against a progressive incumbent who is facing down at least $10 million in attack ads from AIPAC, a right-wing organization committed to empowering the Netanyahu government in its barrage of Gaza. Jones may very well win in November, since the district has enough of a Democratic lean. He might get to Congress and evolve, like Torres, into one of AIPAC’s great allies. All those high dollar fundraisers could drown out the progressive outrage. Like any ambitious New York politician under the age of forty, he may look in the mirror and see a future senator, governor, or president. That is, of course, if he gets back to D.C. Jones can justify his evolutions by declaring, merely, he is following the will of his constituents, and there is truth to that. Voters, though, might wonder what swirls at the core of Mondaire Jones. Who is he? What does he believe? Is there any there there?

This is why local reporting is important, as opposed to blindly voting Democrat.

I grew up there, it is nice to read such perceptive reporting on a place I know well.

My unscientific impression (confirmed by the tone of your reporting on this race) is that Bowman is doomed. My parents still live in the district and I've been driving around it doing some errands to help them move. You don't see any Bowman lawn or window signs even in the more racially diverse parts of White Plains. I've only seen Bowman signs in the parts of Yonkers adjacent to the Bronx. There are more Latimer lawn signs than I've seen for any previous political campaign in Westchester, and I assume that the lawn signs mostly correspond to Jewish voters who are registered Democrats and will make a point of voting in the primary. When Bowman was running against Engle there weren't nearly as many lawn signs, and even in rich Jewish neighborhoods it was about 50/50 between Bowman and Engel. I know the district includes Wakefield, but I can't imagine that the people down there are as jazzed up as the people further north, who see this primary as a referendum on Israel.

It is sad, meaningless gaffes aside Bowman seems more solid as a politician and a human being than Jones, but I worry Jones is the one with a political future.