A Long and Winding Road

Reflections on "Glass Century," two months later

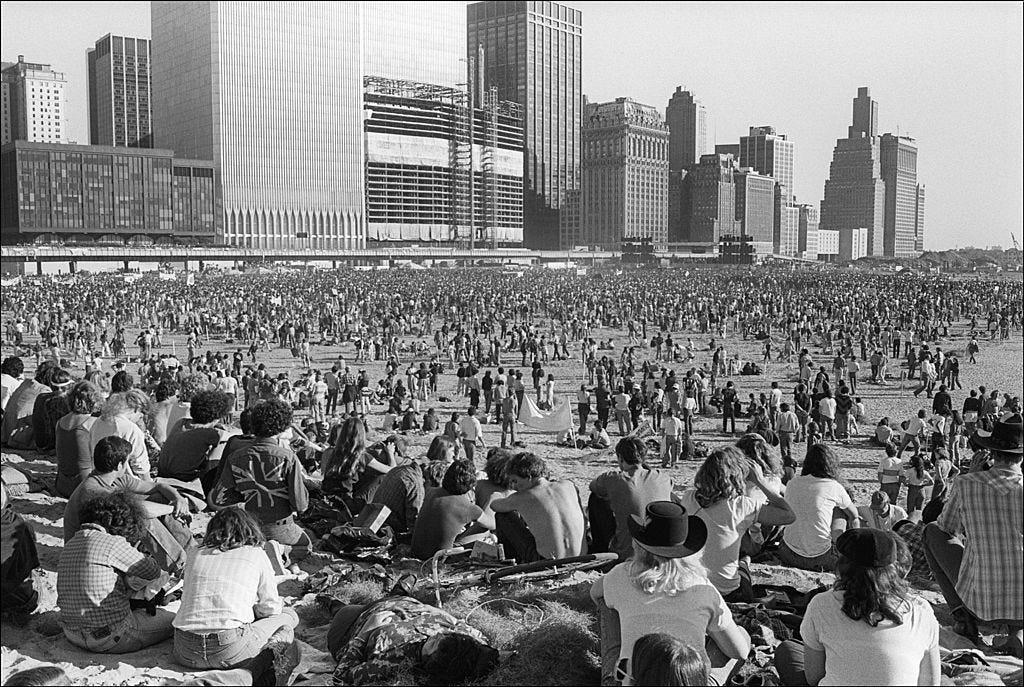

On May 5th, my new novel, Glass Century, was published. You may have known this because you read this newsletter. In fact, if you joined up at any point in 2025 and read with even cursory attention, you may have heard about this book, a family saga and social novel spanning from the 1970s to the pandemic. This was, of course, entirely intentional.

I am thirty-five now; old enough to have spent more than a decade toiling at a trade, and young enough to still have some greenery to work with. Glass Century was not my debut book, nor even debut novel—I had published two other novels, to little attention, and a work of nonfiction—but it in many ways felt like a debut, like I was one of those debutantes nervously descending the staircase. I’ve been known, chiefly, for my writing and reporting on politics, as well as my essays. Glass Century was never a pivot—not in my mind, anyway—but I understood, to most of the public who read what I wrote, it was a new venture. Huh, Barkan is a novelist, too? My sense is, in the twentieth century, this would have been a smaller hurdle to overcome because the worlds of fiction and nonfiction merged much more seamlessly. Prominent journalists and essayists wrote novels, and novelists would, on a quasi-frequent basis, publish essays or even reportage. Jimmy Breslin wrote novels. Joan Didion wrote novels. Norman Mailer showed up at plenty of national political conventions. James Baldwin was equally renowned for his essays and novels. Now, we’ve got our siloes, our specialties, the journalists a bit more philistine, the novelists a bit less adventurous. I don’t like this very much. A young British writer, not long ago, asked me if I thought of Gore Vidal in my own career—if, for example, I considered myself a version of him—and, without sounding too hubristic, I answered that Vidal was sui generis but he was certainly the ideal I pursued. The novel and the essay, what glorious forms! Why choose? The novel, I’ll always love most. But one can be a bigamist with forms.

Despite the fact that Glass Century appeared with a very small press, it was reviewed fairly widely. It was the first novel of mine to not simply disappear. This has been gratifying, and my sense is there’s more runway left. I do believe self-promotion played a role: today, especially, a writer can’t be quiet about their own work. I do understand the wariness around self-promotion because, before 2025, I never liked talking about my novels much. Writing fiction felt like a sensitive, personal activity, one I undertook in the shadows. Discussing it to any great degree was like opening a door to my inner life, and I’m an introvert at heart. You’ll find personal writing on this newsletter, for example, but not nearly as much as you’d find somewhere else. A novel is not a personal essay, of course. It is far more intimate, though, than a politics column or an essayistic argument. You are naked, your soul flashing at the world. Since I believed so much in Glass Century and had a small publisher, I understood I’d have to talk about this novel a lot if I had a chance to make it stick. The shyness would have to be forced out of me.

And that’s the lesson, I suppose, I can impart to other writers: DeLillo and Pynchon can afford to be gnomic (or absent), but you can’t. In truth, with few exceptions, writers always had to be hustling, whether it was Whitman hawking poems door-to-door or the Modernists self-creating their own mythos in real-time. It is very tough to talk about a work of art. Fiction doesn’t lend itself to soundbites, and never will. Yet there’s a bit of wisdom from an old baseball Hall of Famer, Bob Feller, that I’ve sought to follow, at least in my thirties. Feller, known for relentlessly signing baseballs and talking up his exploits, used to tell reporters—or anyone who’d listen, really—that he was the greatest ever. If you’re not going to promote yourself, he asked, who will? For anyone to believe in me, I’ve got to believe in me. Readers are a distracted bunch. Bashful writers will have a harder time catching them.

All of this comes back to the meta topic, Substack. A Substack on Substack, how trite! I’ve got various thoughts about contemporary literature burbling up in me, some more grandiose than others. I do not know if Substack will save literature. I cannot predict, truly, what is coming next. What I can tell you is that I wrote Glass Century in 2019 and 2020 and felt a great urgency to publish it not long after. I tried, for a year, to get my agent to read it, only to find she was going to pass on it for reasons that were never fully clear to me. I spent another year finding a new agent, one who took the novel on but never seemed overly passionate about it. In 2023, after delays that also never made a terrible amount of sense, the novel went on submission, and it was either rejected or not responded to at all. More than twenty publishers, in some form, passed. In early 2024, nearly fed up, I took Glass Century to the small publisher, Tough Poets Press, that put out my debut novel in 2018 and asked them if they’d like to publish my new novel. Thankfully, they said yes. A date was set for May 6th, 2025.

This spate of delays, as infuriating as they were, would play to my advantage in the end because my Substack would continue to grow. Had I gotten my druthers in 2020, Glass Century would have appeared no later than 2022. If that were the case, my audience, in May 2022, would have been five times as small as it was in May 2025, when it finally appeared. Without Substack, I do not know how my novel would have gained any sort of attention because independent books in this environment, sans Substack, have an extraordinary challenge. Book review sections have dried up and competition is fierce. Substack writers talking about my novel—my novel circulating in that ecosystem—made the difference. The writer Naomi Kanakia has dubbed 2025 “Substack Summer” and that feels right to me because this year has marked its arrival as a platform for effectively promoting and discussing new literature. A writer without a Substack, unless already famous, will struggle for an audience. In the 2010s, Twitter was where books catapulted to prominence, and TikTok briefly took its place in the 2020s. Substack, soon, is going to supplant Twitter/X, and new novels may be made or broken here. Substack, like YouTube, has a lot of growing still to do. Whatever you think about the platform, the horizons are bright.

As for myself and Glass Century, novels do not vanish after two months. At least, they aren’t supposed to, not if the author has a bit of verve and the public is willing to pay attention. I’ll have more books to hammer you with, since I do love to write, and there will probably come a time, at some point, when you hear less about Glass Century. But that novel, I promise, is not going to go gentle into that good night. I worked too hard on it, and care too much. For the author, the novel is a little bit like a child, and we’ve got to be protective of our children. This doesn’t mean our children can do no wrong—bad reviews happen—or others can have differing opinions of our children. What it does mean, though, is staying loyal. Don’t slag your children in public, and don’t be dismissive of your work. Be proud of what you’ve done. Share it with others. Own what you’ve accomplished. A novel, any novel, is a feat, a triumph of artistry and, ultimately, will. You write them alone. You reach, perpetually, inward, and the days with your book may be achingly long and slow. With Glass Century, I’ve tasted some glory. I got to do a launch party that more than one hundred people attended. I went on a podcast with one of my literary heroes. I saw my novel reviewed kindly in one of America’s largest newspapers. But still, you are alone—it’s the solitary art, and the best kind, even when it causes you pain. My first and self-interested piece of advice is to buy my book. But my second is to keep writing. You don’t know when your ship will come in. These kinds of journeys, as I’ve learned, are very unpredictable. And they can end well.

I enjoyed Glass Century. My sense is it is better coming out now than three years ago. It seems to fit the mood better.

Very inspiring for writers on Substack! I'm curious about what it was like to negotiate a publishing deal w/o an agent, even with a small press.