AOC Agonistes

A Democratic ladder climber can't also lead the left

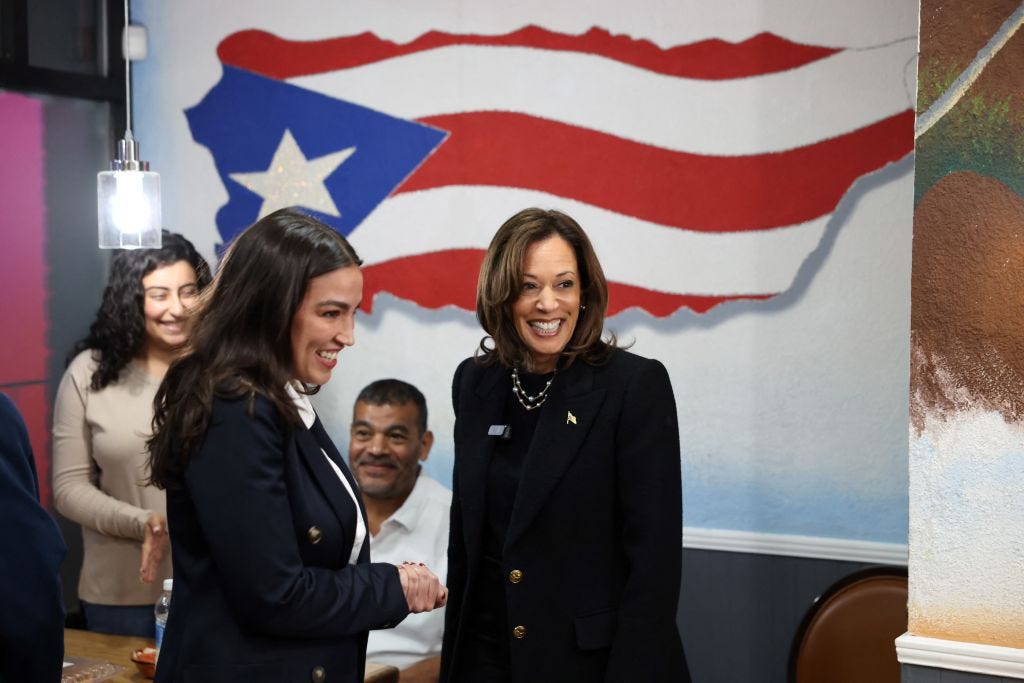

On the morning of the presidential election, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez released a memo. The star congresswoman, seeking re-election herself, wanted the media to know how much she had done for Kamala Harris and the rest of the Democratic Party. “Since August’s Democratic National Convention in Chicago, Rep. Ocasio-Cortez has held more than 30 events in Wisconsin, Michigan, Pennsylvania, Texas, Nevada, and Puerto Rico to campaign for Vice President Harris, Democrats, and progressive candidates up and down the ticket,” her campaign wrote. “Over 7,500 people joined her at these events across the country. Her campaign also supported getting thousands of volunteers to critical swing districts in Pennsylvania in the days before the election. Rep. Ocasio-Cortez on Monday closed out her national get out the vote effort with Vice President Harris at a Puerto Rican bakery in Reading, Pennsylvania.”

“Videos on social media featuring Rep. Ocasio-Cortez consistently perform well,” the campaign boasted, “and effectively move voters to support Democrats.” There were statistics to make the case. A Twitch livestream with Tim Walz racked up 227,000 views. A response to Tony Hinchcliffe’s “floating island of garbage” remark got 10.9 million impressions and 153,000 likes on Twitter/X. Her response to Trump’s McDonald's outing earned 3.7 million plays and 235,000 likes on Instagram, 1.1 million views and 142,000 likes on TikTok, 1.7 million impressions and 23,000 likes on Twitter/X, and 450,000 views on YouTube.

The evolution of AOC has always intrigued me because she is the only famous politician I knew pre-fame. In 2017, I was the first journalist to interview her about her congressional campaign, and when I later ran for office myself, we chatted occasionally as fellow progressives trying to take on the Democratic establishment. We were both born in October 1989 and share generational commonalities: tough memories of 9/11, the financial crisis, and graduating into the kind of precarity that makes today’s inflation seem rather tame. I explain to the youth that everything was much cheaper in 2011 but there were hardly any decent jobs to be had and none of them seemed to pay. I understood her career trajectory very well. And as someone who had written critically about the Queens Democratic Party, I was gratified that someone, at last, was challenging their boss, Joe Crowley.

In this election, Ocasio-Cortez was a proud foot solider of the Kamala Harris campaign. She stumped across America for the vice president, called Jill Stein’s Green Party campaign “predatory”—best, for the Democrats, to have a young leftist do this—and delivered a rousing speech at the Democratic National Convention, where she praised Harris for “working tirelessly to achieve a ceasefire in Gaza.” For many mainstream Democrats, 2024 was when the left-wing rebel grew up and joined the club. Suddenly, the MSNBC set didn’t mind her at all. Whereas Bernie Sanders never seemed particularly enthusiastic about Harris, sensing perhaps she was eager to abandon Joe Biden’s economic populism, AOC was all-in. If she were ten or twenty years older, there would have been chatter about a bid for a cabinet post in a Harris administration.

Until the night of Nov. 5, these moves seemed canny, if ultimately cynical. How could Ocasio-Cortez, who once promised a political revolution herself, be so enthusiastic about a milquetoast product of the California Democratic establishment, a politician who, while racing to the center, was boasting about America’s “lethal” military and her own prized handgun? Harris, on foreign policy, was an enigma, but no one could say with a straight face she was working “tirelessly” for a ceasefire as tens of thousands of Gazan bodies piled up. It wasn’t as if Jake Sullivan or Lloyd Austin needed to seek advice from a former one-term senator from California. Throughout her career, Harris had been nurtured by power elite, and her presidential campaign was backed by many billionaires, including Barry Diller and Mark Cuban. Each were open about their desire for Harris to dump Lina Khan, Biden’s Federal Trade Commission chair and the architect of his antitrust policy; their hope, plainly, was to elect a Democrat who was friendlier to corporate America and Silicon Valley. Harris had even made overtures to the cryptocurrency industry, indicating that their great enemy at the SEC, Gary Gensler, was living on borrowed time. This was AOC’s candidate? But the democratic socialist is ambitious. She wants to be with a winner. Team players get further in D.C., anyway.

The election did not go Ocasio-Cortez’s way. This can be said of any Democrat. What’s rough is that her campaigning came to so little. She outran Harris in her own district, but her Spanish-speaking constituents swerved hard toward Trump. After the “island of garbage” controversy, AOC all but promised an enormous wave of Puerto Rican voters would rise up against Trump. Instead, the nation’s most prominent Puerto Rican politician looked on as heavily Puerto Rican neighborhoods in Pennsylvania and New York City gave more of their vote to Trump than they did in 2020. The youngest millenials and Gen Z did not necessarily follow the lead of the politician who was supposed to be their generation’s lodestar. In a sign of a burgeoning counterculture that the liberal left would love to discipline out of existence, more and more of them chose the incendiary Trump.

Ocasio-Cortez has spoken about an “inside-outside” political strategy which pairs outside organizing and agitation with the painstaking work of legislating within institutions. She’s been a diligent congresswoman, no doubt, and the progressive left in America has been better off for her advocacy. What she may soon come to understand, however, is that one cannot be inside and outside in perpetuity. This election demonstrated that she has mostly made her choice. She wants to be an insider. She might want to chair the Congressional Progressive Caucus one day or run for the Senate in New York. A presidential bid feels inevitable. She might be potent in a Democratic primary for president, if her grip on the electorate—that progressive and Latino coalition—suddenly seems tenuous. If she’s another center-left lawmaker, how will she distinguish herself in a crowded presidential field? She’s got years to ponder that.

What AOC has plainly decided not to do is be a genuine leader of the American left. Sanders does not have a successor. Were he a decade younger, he would probably be contemplating a third presidential bid. This may speak to a paucity of current options on the left than any greater vanity on Sanders’ part. Sanders is not a terribly introspective politician and, even in his eighties, he has seemed to give little thought to what will happen to his movement after he’s gone. He’s an important figure in American history, but he’s not the organizer or party boss progressives and socialists need to increase their power in the future. He has, for good reason, returned to the news cycle because a growing number of Democrats are waking to the reality that his political instincts in 2016 were largely correct: you win on economics and you can’t lurch too far to the left on culture. The Hillary Clinton wing of the party deemed Sanders a racist (“If we broke up the big banks tomorrow … would that end racism? Would that end sexism?”) and soundly rejected his contention, even after the fall of Roe v. Wade, that campaigning on abortion rights wouldn’t be enough to keep winning. He was chastened in 2022, but it became obvious, as the presidential election neared, voters were supportive of referendums legalizing abortion but were not otherwise reflexively choosing Harris. They needed something else to vote for—promises to bring down the cost of groceries, the cost of rent, and the interest rates. Some also wanted a tighter border.

Sanders fits much more neatly into this matrix than Ocasio-Cortez. He has called the concept of open borders a “Koch brothers” proposal. He never wanted to defund the police. And he has embraced alternative, dissident media. When running for president in 2020, he appeared on Joe Rogan’s podcast. Rogan was smitten enough that he endorsed Sanders. The fresh calls for a “Democratic” Rogan to counteract the Trumpian right miss a much more brutal truth: these voters were there for the taking, if only Democrats bothered to listen to them. Ocasio-Cortez, for all her youth and savvy, couldn’t grasp the future as well as a man born during World War II. After the Sanders campaign promoted his appearance on Rogan, Ocasio-Cortez refused to aggressively stump for him in the early voting states. During one campaign speech in Iowa, she even declined to mention Sanders’ name. This was the height of the social justice era, and Ocasio-Cortez was at its vanguard. Progressives, preaching a big tent, were rhetorically closing it in the name of protecting the marginalized. Rogan did not belong, and those who enabled Rogan did not belong. A year later, in the wake of the George Floyd protests, Ross Douthat of the Times posited that Sanders had lost the future. “Rather than Medicare for All and taxing plutocrats, the rallying cry is racial justice and defunding the police,” he wrote. “Instead of finding its nemeses in corporate suites, the intersectional revolution finds them on antique pedestals and atop the cultural establishment.”

This had been true. Now, a new era blooms, and the intersectional left—the so-called woke—is falling out of vogue. Politics and culture are untethering again. Trump’s return will not reverse a trend that had been accelerating for the last three years. Ocasio-Cortez, for all her association with democratic socialism, was an identity-first liberal at heart, someone who was fully fluent in the language of the professional class. Sanders, who grew up poorer than she did and never abandoned the Marxist flavorings of his youth, could never operate in that mode. He believed, fully, in the dream of a multiracial working-class coalition. He knew, to get there, he would have to knit together disparate clusters of human beings—those, in fact, who held views that might be considered impolitic or even ugly. There was no shunning Rogan if that was your grand goal: the working class listened to him, and so Sanders would go there. This was why he showed up on Fox News, too.

Sanders, as a candidate, was plenty flawed, and it’s reasonable ask why, in Vermont, he ran behind Harris on Tuesday. He is not always a nimble thinker. While calling himself a socialist—and limiting his appeal, ultimately, among the broader electorate—he has done little to bolster the only functioning socialist organization in the United States. Our Revolution, which was supposed to be the vehicle for Sanders’ politics, has amounted to little. What Sanders has bequeathed to Democrats is a comprehension, finally, of the need for a class-based politics, one that takes material need seriously. If Sanders was a college graduate, he rarely spoke like one, and he understood why politics had to be made tangible. And for the sake of the left itself, he grasped that it was vital to hold yourself beyond the Democratic establishment. For some socialists, ironically, Sanders was always viewed as too accommodating, endorsing both Clinton and Biden and campaigning for them. He certainly championed the Biden administration. Now, upon Harris’ loss, he is blasting away at the Democratic establishment anew.

Ocasio-Cortez is not. She is not at the forefront of this new reckoning over what a defeated party needs to do. She has a bright a future in Washington if she remains in Congress; she can accumulate seniority, chair committees when the Democrats win the House eventually, and perhaps wait out Chuck Schumer’s retirement. What she will not be is the next leader of the American left. Perhaps she doesn’t want this any longer and is more comfortable playing surrogate for whomever party elites anoint. She didn’t have to campaign harder for Harris than she ever did for Sanders. She obviously felt motivated. A more difficult question for her might be, as the decade wears on, where are political base truly resides. If Latinos are too culturally conservative for her and young leftists drift away, what does she have? Will she, one day, see the utility of Rogan or Lex Fridman or Theo Von and go where the young now congregate? Will she break from her professional class cloister? If not, she’ll only matter so much.

It always seemed to me that progressives and Democrats rejected Rogan not because they didn’t grasp his immense popularity, but precisely because they did. And legitimizing him within their circles would’ve meant diluting their own influence.

AOC is so young that she has time to evolve as she herself matures and as our politics evolve. It will be fascinating to watch her career.