This Is the Zodiac Speaking

A chase through the dark heart of America

The darkness at the edge of the modern consciousness is usually a man with a gun.

Intimate death might be the most terrifying death. Mass casualties—outside of the spectacular or the surreal—tend to numb, whether they spring from warfare or viral outbreaks, and it is in the titanic math where comprehension fails. This is one reality of life lived among machines, as it will always be until something truly apocalyptic comes along. What we fear, in the meantime, is the personal. The killer in the night. Wrong place, wrong time. A bullet smashes through skin and the seconds bleed away or a knife plunges deep toward bone. There is no way to rationalize what happens next. There are no more appeals to make. The night closes, and you’re becoming a headline.

Mass society did not invent the serial killer—a term that did not come into vogue until the 1980s—but mass society, with its radios and televisions and bodies converging in finite spaces, made him what what he is, what we understand him to be. Today, the most notorious and sadistic remain as famous as athletes and entertainers, gods of their own twisted underworlds. Ted Bundy. John Wayne Gacy. Son of Sam. The Zodiac Killer, whom police never found. All bubbled up in the second half of the twentieth century, at a time when the dark currents that course through the culture today were first gaining ground and ruining lives. They killed until they were stopped or, in the case of Zodiac, they killed until they receded into history. The police-state, in a world before ubiquitous computer networks and forensic mastery, could only do so much.

Jarett Kobek, the author of I Hate the Internet and the very underrated The Future Won’t Be Long, believes it’s possible he’s found the Zodiac Killer. In two new books being released simultaneously, Motor Spirit: The Long Hunt for Zodiac and How to Find Zodiac, Kobek tells a cultural history of the murderer—infamous for the taunting letters sent to newspapers and the ciphers that came with them—and makes a compelling case for Zodiac’s true identity, a Californian who died in 2007. Kobek is an amateur sleuth, as he notes, but he has come as close as any to cracking the case through a study of Zodiac’s writings, a solved cryptogram, and dogged library research, the sort that too few do these days. Zodiac, Kobek argues, could likely be a man named Paul Doerr, a comics and science fiction-obsessive who belonged, for a time, to the Minutemen, a dangerous far-right group that flourished during the anti-Communist fervor of the 50s and 60s.

This is the news and what will set Zodiac hunters aflame, of which there are many. Kobek has tipped off the FBI and the San Francisco Police Department. Since Zodiac tips come in frequently, it’s unclear when this theory will be followed up on. Since Doerr is not alive to be arrested, the urgency may not be there.

But what beckons you onward is how Kobek situates Zodiac in the context of the moment we dwell in today. He is a writer first and a cultural critic, and it’s in Motor Spirit where we find ourselves enveloped fully in the madness and the myth. In the time of Zodiac, at the end of the 1960s, reality and fiction seemed to crash together for good. In our tiring 2020s parlance, there was a vibe shift, but it was much more than that, with the murdering of icons and the curdling of a counterculture and the violence, rising slowly like seawater, that suddenly seemed to be everywhere. California was the locus. “The future always looks good in the golden land, because no one remembers the past,” Joan Didion once wrote.

The Zodiac Killer’s hunting ground was the San Francisco Bay Area, beginning in late 1968. As Kobek makes clear, the story of Zodiac, in all its terror and unsettling allure, cannot be separated from San Francisco, ground zero of the Beats, the hippies, and the Summer of Love. There is the San Francisco of the imagination—Flower Children in Golden Gate Park, Scott McKenzie crooning through the radio—and the San Francisco the culture would rather forget: the city where people got their motor spirit.

Zodiac had five confirmed murders but claimed at least thirty more, most of which either have been debunked or never verified. His murders came amidst a backdrop of increasing death and a media thirsty to broadcast all of it. “A wave of drug-induced violence starts around 1966 and won’t end until the 1990s,” Kobek writes. “The Golden State is awash in blood. The reporting is more real than the events. The country has gone mad, its people are hopeless in their insanity.” By the time Zodiac shoots and kills a teenage couple, David Faraday and Betty Lou Jensen, shortly before Christmas 1968—firing with .22 long rifle rounds into the night—King is dead, the Kennedy brothers are dead, and Richard Nixon is the president-elect. The governor of California is a former movie actor named Ronald Reagan. His implicit promise, with the Californian Nixon ready to enter the White House, is to break the neck of the counterculture. The war in Vietnam, inevitably, is a disaster.

Back home, the murder rate steadily climbs in large American cities. The causes are debated to this day. The fringes of the American right and left each race toward violence, with white supremacist factions amassing weapons while the Weathermen begin to bomb the U.S. Capitol, the Pentagon, and NYPD headquarters. Life goes on, but cataclysm—or the threat of it—becomes a new normal. In San Francisco, the lurid undercurrent of the counterculture is found in the gang rape and murder of Ann Jiminez, which comes on December 26th, just six days after Zodiac kills Jensen and Faraday.

Zodiac does not kill Jiminez. She is 19, a runaway to the famed Haight-Ashbury, the nexus of the Summer of Love. “The Haight has changed,” she wrote in a letter to her sister dated Christmas Day. Drugs are everywhere. Soon, at least six young men and three girls in her building will gang rape her for up to three hours, all to “teach her a lesson” for allegedly stealing her roommate’s boots. She dies from a blow to her temple after being kicked, beaten and dragged down two flights of stairs. The attackers are high—one has shot a dimebag of speed. Jiminez’s roommate, describing her disgust with Jiminez, declares she doesn’t have “motor spirit.” She doesn’t have amphetamine psychosis. “San Francisco is the epicenter,” Kobek writes. “San Francisco is where you get motor spirit.”

The investigators assigned to the Jiminez case, Dave Toschi and Bill Armstrong, will soon be focusing on Zodiac.

The story of Zodiac is, partially, the story of police failure. Incompetence cannot explain all of it. Before mass surveillance and DNA, their tools are inadequate to the task. “Criminal justice is a story that society tells itself to fashion order from chaos,” Kobek explains, even as he will later detail the travails of Toschi, who grew in fame with Zodiac and later penned fake letters praising his own policework. “Unless someone screws up, unless someone makes a threat before they commit a crime or are incapable of covering their tracks while in commission of that crime or there’s a later confession, then the crime will never be solved. If it is solved, there is a reasonably decent chance that the solution will point to someone who isn’t the criminal.”

The midcentury killers in prison for the crimes they commit are largely those who aren’t terribly sophisticated. The rest, particularly if they’re poor or nonwhite, are there as scapegoats juries can easily file away. Zodiac is not perfect, but he is not sloppy. And he is hungry for recognition.

What makes Zodiac—who, even now, is enough of a household name that the internet can joke implausibly of the 1970-born Ted Cruz being the man behind it all—famous is not the killing itself. Shootings are not remarkable in the late 60s. By the summer of 1969, Charles Manson has the culture in his grip. He is the sadistic Svengali of SoCal. The Manson Family and the murder of Sharon Tate, other than maybe the Moon Landing, is all anyone wants to talk about.

To break through, Zodiac must become a media creation—he must have a brand, a gimmick, a way to reach through the noise and take the culture by the throat. Not all murderers write letters to the press. Zodiac will.

The first letter is mailed on July 31st, 1969, sent to the offices of the Vallejo Times-Herald, the San Francisco Examiner, and the San Francisco Chronicle. By then, an unknown man has shot and killed a young woman, Darlene Ferrin, in Vallejo and badly wounded the man who was with her, Michael Mageau. The shootings come just before midnight on July 4th. Mageau remembers, while sitting in Ferrin’s car, the killer carrying a flashlight and pointing it in his eyes before opening fire. Just after midnight, a man calls the Vallejo Police Department to take credit for the murder, as well as the killings of Faraday and Jensen. Police trace the phone call to a nearby gas station but have few other leads.

The letters bring it all together. “Dear Editor,” Zodiac begins, “This is the murderer of the 2 teenagers last Christmass at Lake Herman & the girl on the 4th of July near the golf course in Vallejo To prove I killed them I shall state some facts which only I & the police know.” He claims to know 10 shots were fired, the “girl” was wearing “patterned slacks,” and the brand name of the ammo used. Included in the letter is the symbol that will make him famous: a circle quadrisected by a cross, resembling a gun scope or crosshairs.

Included with the letters are ciphers that the killer says must be printed in the newspapers. “If you do not print this cipher by the afternoon of Fry. 1st of Aug 69, I will go on a kill rampage Fry. night.,” he warns. “I will cruse around all weekend killing lone people in the night then move on to kill again, untill I end up with a dozen people over the weekend.”

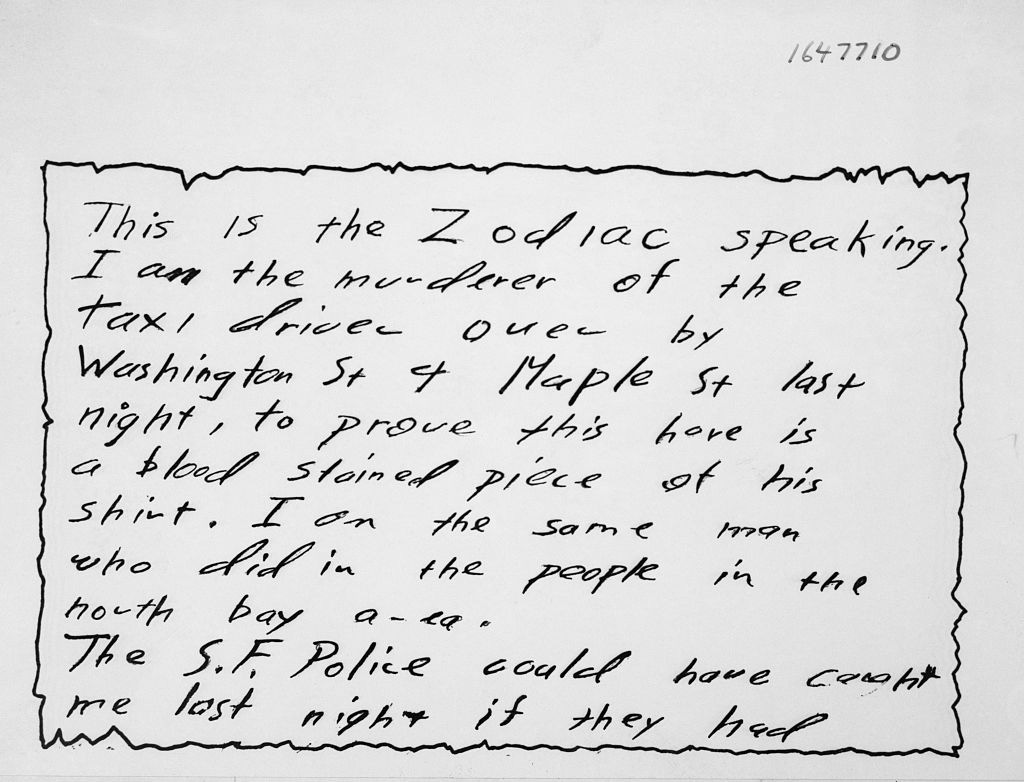

Zodiac is not yet Zodiac. He hasn’t christened himself. He will do this in a letter published August 4th. “This is the Zodiac speaking,” the letters begins. “In answer to your asking for more details about the good times I have had in Vallejo, I shall be very happy to supply even more material.” He does, describing how he shot and killed the two teenagers. And he ends with some blend of warning and lament: “I was not happy to see that I did not get front page coverage.”

The police still don’t have any serious leads and the case is not yet a phenomenon. Zodiac, as he now calls himself, has not yet killed in San Francisco, where real attention will come. Three claimed dead bodies meet the bare definition of a serial killer.

The ciphers and letters, though, are enough to keep news cycles going.

At first, newspapers don’t quite cooperate. They call him the Vallejo Killer or the Cipher Killer. In Kobek’s telling, there’s a possibility that in the way Zodiac described his killing of Farraday and Jensen—using a pencil light technique that might have been copied out of a 1967 advertisement in Popular Science—he may have been taking credit for what he didn’t actually do. That’s one challenge with Zodiac: he talks a big game and will keep talking one for a while.

Readers of the newspapers write in to quickly crack one of Zodiac’s ciphers. The mythos will take another leap forward. The message reads:

I LIKE KILLING PEOPLE BECAUSE IT IS SO MUCH FUN IT IS MORE FUN THAN KILLING WILD GAME IN THE FORREST BECAUSE MAN IS THE MOST DANGEROUE ANAMAL OF ALL TO KILL SOMETHING GIVES ME THE MOST THRILLING EXPERENCE IT IS EVEN BETTER THAN GETTING YOUR ROCKS OFF WITH A GIRL THE BEST PART OF IT IS THAE WHEN I DIE I WILL BE REBORN IN PARADICE AND THE [missing text] I HAVE KILLED WILL BECOME MY SLAVES I WILL NOT GIVE YOU MY NAME BECAUSE YOU WILL TRY TO SLOI DOWN OR ATOP MY COLLECTIOG OF SLAVES FOR MY AFTERLIFE EBEORIETEMETHHPITI

The imagery chills. Kobek argues that police and various hunters of Zodiac over the decades have made the mistake of ascribing too much to the name itself. For anyone in late 60s California who wanted to make a vague gesture toward the occult or the spooky, Zodiac was an obvious choice. “It’s the absolute lamest, squarest attempt to sound like a sinister freak,” Kobek writes. “It’s what someone’s dad would come up with.” Unlike another killer who would emerge later on, the original Zodiac ties none of his crimes to astrological signs.

Manson will bump Zodiac out of the news. The murders are everyone’s worst nightmare of the counterculture gone awry, a savage cult leader who once palled around with a Beach Boy and believed Beatles lyrics heralded an apocalyptic race war. It takes until the end of September, when Zodiac kills again, for the news cycle to shift.

Two college students are targeted, Bryan Hartnell and Cecelia Shepard. They are picnicking at Lake Berryessa, the largest lake in Napa County. A white man, standing just under six feet tall, attacks them wearing a black executioner’s style hood with clip-on sunglasses over the eye-holes. He points a gun at them, claiming to be a convict escaped from jail. Rather than shoot, he tells Shepard to tie up Hartnell with the plastic clothesline he’s brought. At first, Hartnell believes it’s a strange robbery, but the man draws a knife and stabs them both repeatedly. Hartnell is wounded six times, Shepard ten.

He then hikes 500 yards, as the two are bleeding out, and draws, in black felt-tip pen, the circle quadrisected by the cross on Hartnell’s car door. In full, he writes:

Vallejo

12-20-68

7-4-69

Sept 27–69–6:30

by knife

At 7:40 pm, a call comes in from a pay phone to the Napa County Sheriff’s Office. The caller wants to “report a murder—no, a double murder” and claims he did it. He is wrong, though he doesn’t know it yet—Shepard will die, but Hartnell will survive. A man and his son fishing nearby hear their cries for help and summon park rangers. Hartnell and Shepard are both transported to a nearby hospital. Shepard loses consciousness and never regains it. Hartnell lives to tell his tale of Zodiac.

Kobek reproduces the full transcript of the police interview with Hartnell, who is the only person to talk at length with Zodiac and survive to talk about it. His Zodiac is less sinister occultist than nerve-wracked working-class schlub, blabbering about escaping prison and fleeing to Mexico because he was “flat broke.”

One fundamental contention Kobek makes, rebuking other Zodiac researchers, is that the man who pulled off these murders—the aforementioned Doerr—was a byproduct, rather than a “product,” of the counterculture. He is older, more embittered, ready to exact vengeance against the radicals and hippies who have warped the decade. They’re kids “who rejected everything the lower orders had achieved during California’s post-World War Two prosperity. Worse yet, the kids wanted the lower orders to feel bad about what they’d achieved.”

Resentment, though, will not make Zodiac famous. It will be the letters, the cryptograms, and now the hood and rope, which echoes the Manson Family murders. Zodiac happens in “the imagination zone of the press,” growing in stature as the police flail after him, unable to produce enough evidence to drag in a suspect. At the end of September, Zodiac—still the Cipher Killer—scores the front page of the Examiner. He’s where he wants to be.

In the city of San Francisco, Zodiac is fully born when he kills a cabdriver named Paul Stine. There’s no evidence he’s known any of his victims previously. Stine is like Shepard, Ferrin, Jensen, and Faraday—wrong place, wrong time. In October 1969, he picks up a white male passenger who, shortly after, shoots him in the head with a 9mm handgun, killing him. They’re in Presidio Heights, a neighborhood nestled near the Golden Gate Bridge. The murderer swipes Stine’s wallet and car keys and tears away a section of his bloodstained shirttail.

Three teenagers see the dead victim and the killer leaving his car. One calls the police and puts in a description: white male adult, early forties, heavy build, reddish-blonde crew cut. He’s wearing eyeglasses, dark brown trousers, a dark navy or black Parka jacket, dark shoes.

Instead, a description is wrongly put out for a Black male adult. Systemic bias and incompetence collide. Police cruisers are immediately dispatched to the area and this is their best and last chance to catch Zodiac. One officer later states he saw a man matching the teenager’s description—white, heavy build, eyeglasses—but didn’t know at the time that was who he should be looking for. He had been told to find a Black male. The officer’s description matches how Hartnell, the young man who survived the stabbing attack, saw Zodiac.

The killer walks off into the night.

The rise to infamy comes through the press. There’s no other way. In October 1969, just days after Stine’s murder, the Los Angeles Times, which has a greater reach than any San Francisco paper, runs an exceptionally long story on the Zodiac Killer. It does not mention Stine because Zodiac has not yet claimed him. Instead, it’s a flabby feature, a lookback, and it does what the other newspapers haven’t—it brands the killer the way he wants. The Cipher Killer is no more. Zodiac is here.

The Times piece, according to Kobek, is sloppy, riddled with factual inaccuracies and unfounded assumptions about Zodiac based on alleged expert testimony, like that the misspellings indicate he has a lousy job or that he stabbed Shepard in a pattern resembling the crosshairs or that he only kills women. Regardless, Zodiac will now have fame on his terms.

More letters arrive. In one dated October 13th, Zodiac officially takes credit for Paul Stine’s murder, tucking a piece of his bloodstained shirt into the envelope sent to the Chronicle. He taunts the police and threatens to “wipe out a school bus some morning. Just shoot out the front tire & then pick off the kiddies as they come bouncing out.” The letter closes with his trademark crosshair symbol.

This letter is page one news. Panic is here. Kobek astutely points out that the Chronicle, by indicating the letter was written in blue ink with a felt-tip pen, has offered a roadmap to a generation of poseurs. Many will soon pretend to be Zodiac.

In November 1969, Zodiac sends another letter. This will be later known, among afficionados, as the “Bus Bomb” letter and it runs seven pages. Like the last dispatch, the envelope has a piece of Stine’s bloodied shirt. Zodiac claims to have killed seven people, though there isn’t hard evidence for this, and never will be. “I have grown rather angry with the police for their telling lies about me,” he writes. “So I shall change the way the collecting of slaves. I shall no longer announce to anyone. When I comitt my murders, they shall look like routine robberies, killings of anger, & a few fake accidents, etc”

It's a convenient boast, one that will permit Zodiac—and those tracking him—to ascribe all kinds of mayhem over the coming decades to him. He is an early terrorist, maximizing the power of fear. And since he’s delivered already, his words must be credible now. In the letter, Zodiac describes how he will build a bomb with ammonium nitrate fertilizer and use it to annihilate the school bus. “I think you do not have the manpower to stop this one by continually searching the road sides looking for this thing.” He taunts the police further, claiming he spoke with cops on the night he killed Stine.

The police are scrambling. For a time, the SFPD even recruits an astrologer. As 1969 bleeds into 1970, Zodiac fever arrives, as the authorities and press warn of imminent attacks. The schoolchildren aren’t safe. The press and the police speculate on motives. Handwriting experts, analyzing the Zodiac letters, venture new guesses: the killer is “impotent,” “shrewd,” “paranoid.” A man claiming to be Zodiac calls into a television station and talks about wanting to kill kids, but when his voice is played for Bryan Hartnell, the college student who survived the stabbing, and the dispatchers who heard earlier phone calls, they don’t recognize it. The caller is a fake.

The fever holds. People are arrested on the suspicion of being Zodiac but clearly aren’t Zodiac. Foreign reporters descend on San Francisco, wanting to know more about the new letter-writing killer taking America by storm. The police have almost nothing to go on; journalists have everything.

Before the internet, the newspapers are everything, and Zodiac is prime newspaper fodder. Another greeting card arrives with a cipher that won’t be cracked until 2020. Zodiac asks for the cipher to be printed on the “front page.” It’s another dispatch from hell with no new information.

I AM NOT AFRAID OF THE GAS CHAMBER BECAUSE IT WILL SEND ME TO PARADICE ALL THE SOONER BECAUSE I NOW HAVE ENOUGH SLAVES TO WORK FOR ME WHERE EVERYONE ELSE HAS NOTHING WHEN THEY REACH PARADICE SO THEY ARE AFRAID OF DEATH I AM NOT AFRAID BECAUSE I KNOW THAT MY NEW LIFE WILL BE AN EASY ONE IN PARADICE LIFE IS DEAT

Even if Zodiac doesn’t kill again—no school bus is ever bombed—he has joined the future. The press can only tire of him for so long and the police will keep scurrying around, hunting down bad tips. On the first anniversary of the Jensen and Faraday murders, Zodiac sends a letter to a famous attorney, Melvin Belli, claiming he needs help or he will “loose control” and “take my nineth & possibly tenth victom. Please help me I am drownding.” Again, he threatens to bomb the schoolchildren.” Belli’s name had been mentioned in Herb Caen’s Chronicle column next to an item about Zodiac.

Kobek argues there’s a pattern to Zodiac: he writes after he’s mentioned in newspapers, feeding a loop of fresh coverage. The media writes on Zodiac, Zodiac writes to the media, and the media writes on Zodiac again.

It helps that Zodiac, at the dawn of the 70s, is an obsession. A Virginia state assemblyman who is an amateur astrologer claims Zodiac plans his murders according to the waxing and waning of the moon. In Los Angeles, five people call the LAPD claiming Zodiac sounds like someone they probably know. A Zodiac wanted poster is brought to the San Francisco Hall of Justice. A reporter in Ohio runs a classified ad asking Zodiac to give himself up in return for legal and medical help. Also, the reporter will “write novel on your life and series of articles for widespread publication.”

In April 1970, Robert Michael Salem, a gay man, is murdered in San Francisco. He’s stabbed in the chest and the back, his throat cut, an ear removed. He’s nearly decapitated. A bloody Egyptian ankh has been drawn on his stomach. On the walls, in Salem’s blood, is the message “Satan Saves Zodiac.” In normal circumstances, the newspapers of that era could downplay or ignore altogether the murder of a gay man, but the Zodiac angle can’t be dismissed. Frenzy builds until the fingerprints found in the apartment do not match the partials taken from Stine’s cab. Frenzy momentarily abates.

Zodiac, though, cannot die. He keeps sending letters. In one, he makes a curious request: people in San Francisco should wear buttons with his gun scope symbol around town. He says doing this will keep him from building and deploying his bus bomb. Another letter arrives expressing anger about the lack of Zodiac buttons and includes ciphers that are all but unsolvable. He now claims, instead of building the bus bomb, he shot “a man sitting in a parked car with a .38.” No evidence, though, links him to such a killing.

Suspects are continually floated. The writer Robert Graysmith, in his 1986 book Zodiac, advances the possibility of a pedophile named Arthur Leigh Allen as Zodiac. In 1992, Allen dies, and in 2002, the SFPD develops a partial DNA profile of Zodiac from saliva on stamps and envelopes of Zodiac’s letters. Allen’s DNA does not match. The 1966 murder of an 18-year-old college student, Cheri Jo Bates, is theorized as Zodiac’s first victim, with the Chronicle’s Paul Avery taking up the cause. Strong evidence never emerges for such a link. In 2007, David Fincher’s Zodiac is released, based on Grayson’s books.

The Zodiac sleuthing never ends. It is a relic of the twentieth century well at home in the demented twenty-first.

Kobek, as he writes in How to Find Zodiac, is a reluctant sleuth. He struggles to complete a new book after 2019’s Only Americans Burn in Hell, starting first on an account of every murder in San Francisco in the year 1974. He tries out a biography of a Swiss banker. The pandemic interrupts his research, cutting him off from the Swiss Archives. Another project on YouTube stars who’ve committed suicide fizzles. Like Norman Mailer in Armies of the Night, Kobek writes in the third person, but he’s not an intrusive narrator here. He is a character ready to recede when need be.

Kobek gets an idea: write on Richard Gaikowski, the San Francisco writer and filmmaker, now deceased, who some on the internet insist is the Zodiac Killer. Kobek does not believe this at all. Like with other Zodiac suspects, the evidence is flimsy. It’s far weaker than Graysmith’s case for Allen.

The Zodiac Killer had an American obsession with fame, with being known far and wide. He read his own press and sniffed hungrily for more clippings. “The mass shooter had a special knowledge,” Kobek writes. “They knew that America was not going to give them what they wanted. If they could not be rich and famous, they could be dead and famous.”

If Gaikowiski didn’t do it—nothing credible ties him to the murders in Vallejo or San Francisco—then who is this person who scrawled out letters and ciphers? Who dared to compete with Manson?

Kobek decides that someone who wrote to newspapers to broadcast his murders probably had some experience writing to newspapers—and with writing generally. But he doesn’t want his book to be a hunt for Zodiac. It was intended to be, as Motor Spirit became, a story of a cultural moment, of myth. “He couldn’t think of anything more boring than finding Zodiac, of having the magic word appear in the first clause of one’s obituary,” Kobek says of himself. A correspondence with a friend who is an expert on Golden Age comics happens upon a different possibility: Zodiac’s letters appear to contain references to comics and science fiction of the time approaching midcentury. Anyone who wrote the letters might possess some useful knowledge of the period. There are possible callbacks, in Zodiac, to a rare 1952 comic, Tim Holt #30. A card Zodiac sent contains a strange symbol that appears to mimic something found in Tolkien.

It was still the time of fanzines, low-cost periodicals on extremely cheap paper that told stories of the future. Astronauts, space aliens, superheroes. “Toilet literature consumed by the working-classes,” Kobek writes, and therefore “freed from the pretensions of Literature.” Since the Zodiac killings started in the Vallejo area, Kobek decides to punch “Vallejo Fanzines” into a Google search. A PDF scan of a science fiction fanzine called Tightbeam pops up.

On its twelfth page, there is a letter from a man named Paul Doerr. A return address is included. Box 1444, Vallejo, California, 94590.

Doerr is fuming about rising postal rates, the “anti-poverty” people who had forced the post office to hire “unqualified workers.” The letter meanders, and ends with a question: “Is anyone around the Bay interested in skin diving or sailing?”

From there, the chase through time begins. Kobek’s stated goal is to rule out Doerr as a Zodiac suspect, as he ruled out Gaikowski. One Zodiac letter demonstrated a knowledge of sailing and navigation, and internet searches for Doerr revealed that he served in the Navy as a medic during World War II and Korea. Born in 1927, Doerr worked for decades at the Mare Island Naval Base in Vallejo. He died in 2007.

And? A knowledge of sailing doesn’t make Zodiac and Kobek is self-aware of the road he’s traversing down. Identifying a new Zodiac suspect is old hat in the internet age, ever since it became possible to speed across time and space to knot threads together that have little to do with each other.

One advantage Kobek has is that Doerr, unlike other suspects, was an obsessive and inveterate letter writer. Doerr couldn’t help himself. He left an immense paper trail. He seemed to relish in placing classified ads. He was a certified gun nut, placing ads for assault rifles and all kinds of weapons, looking to buy and trade. He did it in the 1960s. He did it in the 1980s. He fantasized, in his writings, about killing young people. A hard right libertarian, he was an open supporter of George Wallace, the arch-segregationist who ran for president in 1968, 1972, and 1976.

As Kobek plunges, more bits of intriguing circumstantial evidence are excavated. Doerr, for one, was a local who knew cryptography. In Hobbitalia, a J.R.R. Tolkien fanzine, Doerr wrote a cipher, broken by Kobek, that asked for fans of Tolkien to meet up for a “Tolkiencon.” A postmark on the fanzine from Doerr showed a 12-cent stamp from the Prominent American line, the same used on most Zodiac correspondences. Another coincidence Kobek notes, though isn’t overly enthusiastic about.

One question lingering over Zodiac lore is why he dressed in a medieval executioner’s hood in an attempt to kill both Bryan Hartnell and Cecelia Shepard at Lake Berryessa. The outfit, to the surviving Hartnell, was curious and was not one Zodiac was ever known to don again. Kobek’s research turns up yet another point of intrigue: a very large Renaissance fair ran the weekend of the murder, an hour and a half drive from Lake Berryessa. It was a place where thousands of people dressed up. It was plausible for Doerr to be there.

Still, Kobek is aware that doesn’t add up to enough. And part of the pull of How to Find Zodiac is Kobek’s attempts to fight his own confirmation bias. He keeps running into Doerr, who ran classified ads in both science fiction and underground hippie newspapers in the 60s and 70s, hoping to build communal farms or get a “girl for sailboat trips” even if public records indicate he was married and had a child. In one ad, he offered to sell unlicensed and illegal mail order guns. In another magazine Doerr created—he had many of these odd, seemingly short-lived ventures—he railed again gun control and the ban on mail order guns, something Zodiac referenced in one of his taunting letters, telling the police his murder weapon was untraceable.

The search for Zodiac picks up when Kobek discovers Doerr writing out, in one of his magazines, the formula for an ammonium nitrate or ANFO bomb, the same described by Zodiac in his threat to blow up a school bus. Both, according to Kobek, make the identical mistake of neglecting the primer, something that explodes first inside the mixture and triggers the larger, deadlier explosion.

ANFO would make its public debut in 1970, when radical students protesting Vietnam blow up a central building at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Later used in a number of bombings worldwide in the 70s and 80s, ANFO becomes most known in the United States for the Oklahoma City bombing of 1995.

What’s notable, for Kobek, is that Zodiac displayed a working knowledge of ANFO before 1970. The formula appears chiefly in specialty publications that can be hard to find. Relatively few people knew how to make such a bomb. Doerr, who kept a P.O. Box in Vallejo, was one of those people.

How did Doerr learn about ANFO? Kobek uncovers hard evidence that Doerr, at one point, belonged to a rabidly anti-Communist and racist organization known as the Minutemen, which obsessed over a left-wing takeover of the United States. Their founder was a biochemist from Missouri named Robert DePugh. As a means of keeping members educated for warfare that was supposed to be inevitable, a magazine was issued called On Target! A 1966 edition published the formula for an ammonium nitrate bomb. Another edition advised fellow Minutemen to buy guns that were untraceable, as Zodiac claimed he had done.

It is irrefutable, at the minimum, Doerr belonged to the Minutemen. When DePugh is later arrested, the authorities seize a cache of documents and weapons, including a list of more than 2,800 names—all those who belonged to the Minutemen in North America. Doerr’s name and Vallejo P.O. Box are among them. Kobek uncovers Doerr’s name there while searching an online academic database.

Minutemen publications stressed cryptographic communication. With law enforcement or left-wing elements potentially watching them, they believed it was crucial to know how to communicate in secret.

And finally, there was their mantra: “Traitors beware! Even now the cross hairs are on the backs of your neck.”

A symbol came with the slogan, one that the group recommended its members paint in all public places. The Minutemen put the slogan and the logo on stickers. It was part of an alleged large-scale psychological warfare plot to destabilize American communists, which the group would always insist were everywhere.

The symbol, of course, resembled Zodiac’s crosshairs.

One of Kobek’s contentions is that the internet era has made it far easier to assemble a credible case for the identity of Zodiac. Kobek can read through digitized fanzines, letters, and classified advertisements without struggling to find them in dusty boxes. He can find, online, Doerr’s name in Minutemen documentation. Before the 21st century, little of this would be searchable without a remarkable degree of intensity and luck.

Kobek finds a Google Street View image of Doerr’s house in the city of Fairfield. A little-known feature allows users to view the full history of a location. This sort of privacy invasion had its upsides when people looking at past images of Street View found Joseph James DeAngelo, the serial killer and rapist known as the Golden State Killer, the Night Stalker and the East Area Rapist. A 2007 image of Doerr’s home turns up a vehicle: a dilapidated, American compact car that matches the description of the one Zodiac drove after shooting Darlene Ferrin and Michael Mageau.

Later on, Kobek unearths photographs of the mustachioed Doerr that show he has a striking resemblance to the police sketch of the Zodiac Killer. Kobek prints the photos.

A palindrome in a text quoted by Doerr in a fanzine first mailed in 1970 resolved into a cipher sent by Zodiac three days earlier. It also resolved another Zodiac cipher sent two months later. At the end of How to Find Zodiac, Kobek includes an academic paper he wrote on the subject, and explains extensively how he found the text and the palindrome.

Another discovery is a Doerr murder confession. In 1974, in the letters section of another obscure magazine, Doerr offered counsel to someone embroiled in a dispute. “It might be better if you don’t print this part of my letter,” Doerr wrote. “As you can see I’m not the turn‑the‑other‑cheek, don’t‑get‑involved typed. I was in a vaguely similar situation some years ago and there are fewer people here because of it now. The Law is not dependable.”

In a different magazine, Doerr detailed, more explicitly, how to write a “simple yet difficult-to-break” cipher, the sort that Zodiac employed. This matters because most of the floated Zodiac suspects had no apparent knowledge or connection to cryptography. If there was one truth about the killer, he had a strong grasp of how to encrypt a message.

In other letters, Doerr demonstrated a deep knowledge of crimes in the period. He wrote a 1979 letter that mentioned the horrific murder of James Schlosser, who was dismembered and partially eaten in 1970. According to Kobek, the murder received relatively little coverage in 1970. Yet Doerr, who likely possessed “encyclopedic knowledge of California crime,” managed to never once reference Zodiac in any letter or missive. Zodiac was the gaping hole.

But omission is not enough to prove anything. Rather, it is the accumulation, once-disparate facts beginning to swim together.

Kobek now must believe one of two things. That in the third week of April 1970, a person in the Bay Area was interacting with a 13 character Ancient Greek palindrome that resolved into Z13 and Z32 [Zodiac’s ciphers], and that this resolution could be simulated with a blind, procedurally generated computer test. And that this person in the Bay Area interacting with the Greek palindrome also looked like the Zodiac sketch, owned the right car, knew about cryptography, had knowledge of navigation, addressed letters to local newspapers in the same fashion as Zodiac, was into treasure hunting, knew the ANFO formula, collected comic books, was into space colonization, wrote in multiple fanzines about his desire to kill young people, had almost a decade later remembered the incident that provoked the Z13, once had membership in a group that sent out anonymous letters using the crosshairs symbol, and had written a confession to multiple murders.

And was not Zodiac.

Or.

Doerr was Zodiac.

Was Doerr Zodiac? Without DNA, nothing will be conclusive, and gathering it to make a match will be up to the police or the FBI. Doerr left behind family. Kobek didn’t reach out to them. In the coming weeks, months, or years, Kobek’s theory could be put to the test. If Kobek is right, a chapter in American history will close. The Zodiac hunters will have to find somewhere else to trawl. And if Kobek is wrong, the myth will hold. This is the Zodiac speaking. How many more decades will we know these words so intimately?

Nope comely missed it. The writer is wrong. The Authentic Zodiac is Albert Hurvey Hardeman. Details on The JFK Zodiac Killer Connection FaceBook group page. Case Solved.

Read Thomas Henry Horan’s book (s).

Zodiac is a literary creation of author Robert Greysmith and Velejo (?) county sheriff Hal Snook. None of the five canonical Zodiac murders have any physical evidence in common, and Greysmith lied about the evidence situation in his two books. Greysmith worked at the SF Chronicle and had full access to the phony letters. All of this was done to GIN UP sales of the SF Chronicle

as your author/sleuth Mr K posits - - “The newspapers were everything…” (media-wise). Zodiac is not real… he is a literary creation from a cartoonist who worked at the SF Chronicle.