How Renters in New York City Got a Boost

And why many progressives wanted much more

It is easy and natural, if you live in New York City, to not pay attention to what happens in Albany. The antics of Eric Adams are enough to occupy anyone’s attention and every local ill can feel like some policy failure emanating out of City Hall. But while Adams is, perhaps, the least successful mayor in modern times, he does not have total dominion over the city and cannot be blamed for everything. The governor, through the MTA, controls the subway system, and the state determines the city’s taxation, minimum wage, and housing laws. There is power in being mayor, but much more in being governor. The state legislature, collectively, can also keep New York City in a straitjacket.

Every March (and some Aprils), the governor and state legislature hash out the state budget. This year’s, $237 billion, was several weeks late, blowing past the April 1 fiscal deadline. This fact, on its own, doesn’t much matter; the governor and legislators should focus on producing a better budget, not one that fits a strict deadline. Andrew Cuomo, Hochul’s disgraced predecessor, obsessed over deadlines and exploited rushed budgets to drop in all kinds of policy poison pills. Albany lawmaking remains opaque because legislators and the governor continue to jam many unrelated policy items into a fiscal document. In most states, this kind of haggling would be saved for the legislative process. But Albany, for all the change it’s undergone over the last five years—many younger and more left-wing Democrats have joined the legislature, and Cuomo is gone—still operates, procedurally at least, as it did 50 or 60 years ago.

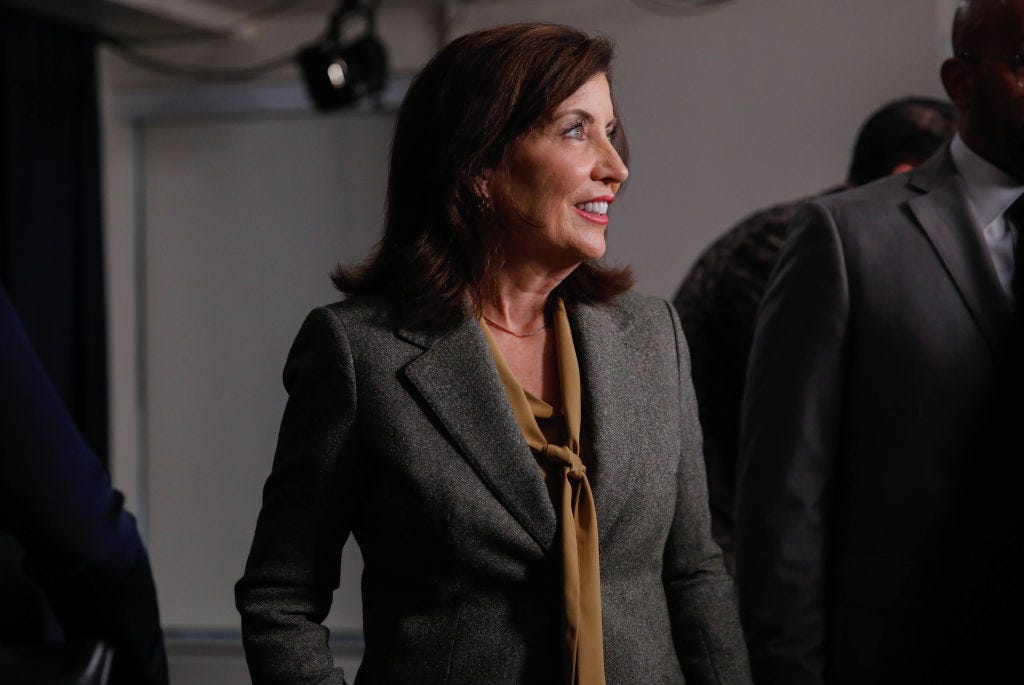

For working and middle class residents in the five boroughs, the most important item of the budget was housing. Remarkably, the housing deal struck between Hochul and the Democrat-run legislature managed to anger conservative and progressive forces alike; both powerful real estate interests and tenant groups sharply criticized the outcome. But the agreement, far from perfect, is underrated, and is going to change the lives of many thousands of tenants for the better. Progressives are smarting because the real estate lobby won some significant concessions and could be primed, in the coming years, to extract more from Democrats. This, for any renter, is worth fearing.

The crux of the budget agreement was that a significant percentage of renters in New York City—between 60 and 70 percent—will be covered by either rent-stabilization or a form of “good cause” eviction, which will limit rent increases and make it harder to evict tenants. If you do not live in a rent-stabilized apartment (your rent increases governed by the city’s Rent Guidelines Board), you might see, by law, smaller increases when your lease is up for renewal later this year or next. Under the new law, rent increases will be limited to over 5 percent plus inflation or 10 percent, whichever is lower. The protections kick in immediately—if you’re renewing a lease in May or June and your landlord is handing out a sizable rent increase, you may very well have the right to challenge it.

The trouble, for tenants, are some of the glaring carveouts in the law.