My 2020 in Reading

The pandemic robbed my time with books on the subway

I don’t account or tabulate much in my life. I don’t keep a diary, a lists of places visited, or track how many steps I take in a day. I have my memories, my inner life, and the writing I produce that all of you see. There are times I wished I tracked more of what I did—how many professional baseball games have I really attended?—but I am usually content to allow the numbers to slip from me, to embrace the haze of existence for what it is.

The exception is my reading. Since the end of 2015, I’ve tracked every single book I’ve read. This was a tradition that began when I wrote occasional posts on Medium and will now be making its debut right here, on Political Currents. (If you care, here’s 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, and 2019). In the past, I graded each book I read and offered a synopsis and analysis, wearing my literary critic hat. As a novelist as well, this is something I have always enjoyed doing. When I’m asked how someone can become a better writer, my answer is simple: read. Read fiction, nonfiction, poetry. Read the news, read magazines, read whatever it is that is around you. Each text consumed becomes a part of who you are—the language, the spirit, and the audacity of it all pulses through you, and will arrive at the oddest moments.

In this pandemic year, I did what I always did and read. Unlike others, my reading productivity didn’t increase much because I had traded time on the subway for time at home. As an outer borough kid from New York City, I’ve always done the bulk of my reading on long train rides, usually the creaky R. Train rides are a time to think and dream; as a teen, and even now, I have tried to make time for my imagination, to allow my interior life to flourish, even in age of such nonstop distraction and inanity. The train rides were mostly gone in 2020, save for the times I went to teach my journalism class at NYU. You’ve read a lot about COVID-19, from me and many others, and I’m not going to dwell on it too much here. I’ll have a project to announce soon about that—I think you’ll be excited—but today is for the books.

Each year of reviewing my reading has always been an opportunity to take stock of how my life has changed. I consider myself lucky to have lived such a varied existence: strange, sometimes thrilling, and typically fruitful. In 2016, I quit my job and ended up on CNN. In 2018, I ran for office and didn’t win. In 2019, I reconnected with writing. And in 2020, in a time of such crisis, I was privileged to be able to be paid to do what I like to do. I take none of it for granted, including your readership. Thank you for that.

In the past, as I said, I would write reviews of every book I read, but I grew less interested in assigning letter grades to individual books. Instead, I began to highlight some of my favorites of the year and list the rest below. I was fortunate, overall, to read many very good books this year, reaching a career high of sorts. Since 2015, at least, I have never read this many books. Last year, though, was close.

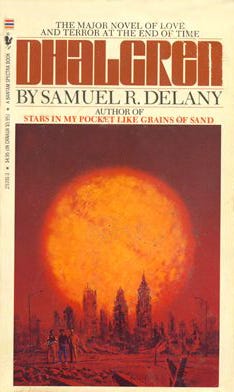

Perhaps the most fascinating and apropos novel of the moment I encountered was the mammoth Dhalgren, considered by many to be Samuel Delany’s magnum opus. My first cousin, who’s a brilliant writer, wrote about Delany in the Times and inspired me to seek him out anew, after reading The Einstein Intersection in college. Delany is one of the more intriguing writers of the second half of the 20th century, a native New Yorker and science fiction pioneer who wrote frankly about race and sexuality at a time when such writing, particularly in the context he labored in, could be a challenge. Dhlagren is classified, broadly, as a science fiction novel, but it’s better understood as a postmodern, neo-Joycean romp through an unhinged urban landscape.

There are no flying saucers, aliens, or planetary federations. As a pandemic read, Dhalgren may be unmatched. Set in the bombed-out Bellona, a fictional city somewhere in the middle of America, the novel follows Kid, a young vagabond and poet who cannot remember his name. Bellona exists both in our world and beyond it—characters reference real cities and real events, like the moon landing, but do not know or particularly care what year it is or how they’ve arrived under such peculiar circumstances. Fires consume buildings without explanation. Food and electricity are scarce. Two moons appear in the sky, and then a supernova sun. On any given day, the lone newspaper could say the date is somewhere in the 1970s, the 2000s, or the 1800s. The Kid meanders, falls in love, attempts his art, and lives, for a time, as the leader of a street gang. It is novel utterly devoid of the mechanics of plot; there is no conventional payoff, no contrived reveal for Bellona.

Days and weeks bend in on themselves. At some point, the city fell from a 20th century peak, and we never learn why. But that’s not the point. Delany published Dhalgren in 1975, and it’s easy to read it as a funhouse distortion of New York in the 1970s—the malfunctioning services, the petty crime, the squatters rummaging through abandoned apartments. At the same time, Bellona can mean liberation. It is a zone beyond the grim machinery of nation-states. No bosses, no commands, no need for money, with plenty of time left over for camaraderie and sex. It is a world haunted by loss, but a world that has also forgotten what it is, in the first place, that has been stolen away. Dhalgren, William Gibson once wrote, is not a riddle meant to be solved. I think that’s right.

Along with Dhalgren, Martin Amis’ Inside Story, published this year, was one of my favorite reads of 2020. Amis is a writer more famous in the U.K. than here; an enfant terrible who rose to fame in the 1970s writing novels on the sexual liberation experienced by his Baby Boomer cohort, Amis—along with Salman Rushdie, Ian McEwan, and Julian Barnes—was a true literary heavyweight of late 20th century Britain. He has continued publishing strong works into the 21st century, including a very good Holocaust novel, The Zone of Interest, and Inside Story, the 71-year-old Amis claims, may be the final “long” novel of his life. It’s a book he’s been trying to write for years; part-memoir, part-fiction, it electrifies the wearying genre of autofiction, infusing it with Amis’ daring and flair. Autofiction, for me at least, can often be too dry a harbor, a series of meditations from minds that don’t warrant any sort of great airing. (Ben Lerner is the exception here.)

At its core, and where the novel is most affecting, is in its portraits of two of the writers who meant the most to Amis: the Nobel Prize-winning Saul Bellow, who was a second father to Amis, and the essayist Christopher Hitchens, an exact contemporary, friend, and eventual soulmate. Amis the narrator, as in Amis the flesh-and-blood man, watches them both wither and die. Bellow, in his 80s, struggles with dementia, unable to process the tragedy of 9/11; once so witty and garrulous, Bellow is reduced to placidly watching Pirates of the Caribbean and forgetting where he resides. Hitchens, who achieved more fame and notoriety in America than Amis, rages against religion and urges on what was, for him, a holy crusade to invade Iraq, baffling old leftist comrades. On a book tour in 2010, he learns he has oesophageal cancer. Amis, with deftness and vulnerability, describes Hitchens’ punishing treatment regimens, his refusal to embrace God, and the steady march of the cancer that will kill his best friend. The famed and miserable British poet, Philip Larkin, dies of cancer too, and there is a current of the novel that concerns a fictionalized lover who tells Amis that his father is really Larkin, not his (actual) father, the novelist Kingsley Amis. Larkin, in some sense, was everything Hitchens wasn’t; the glum son of a Nazi wannabe, he shunned the lush vistas Hitchens raced so headlong toward. Ironically, Larkin seemed to fear dying much more, despite his miserly distrust of the living. Amis saves time for his usual, intriguing fixations—Israel, existentialism, center-left politics, a few useful writing lessons—and all the detours, in their own way, are satisfying. It is a feast of novel, brimming with footnotes, digressions, and the many threads of a life unwound for all to sift through. If this is it for Amis, it is as good a final bow as any.

I read two engrossing biographies this year, one of the writer Nelson Algren, once a titan of midcentury, and the other of the pitcher Jim Bouton, best remembered for writing Ball Four. Colin Asher, the author of the Algren biography, and Mitchell Nathanson, the Bouton biographer, render their lives in full, never dipping into hagiography. Algren lived a whirlwind, if tragic, life, finding great fame but never making enough money—and failing to hold onto what he did. A more artful proletarian novelist who counted Ernest Hemingway among his many admirers, Algren was a committed leftist who never lost his connection to the downtrodden of Chicago, where he lived much of his life. He may have been the first major American writer to render, in frank and brutal detail, drug addiction on the page, capturing the harrowing descent of Frankie Machine in The Man with the Golden Arm. Asher’s research uncovered that the FBI was tracking Algren for decades and likely contributed to his decline, barring him from travel—he had a long-running love affair with Simone de Beauvoir—and future writing opportunities. For Don DeLillo fans, there’s a cameo from the writer himself, where he tells Asher he encountered an aging Algren on Fire Island years before he ever knew he would be a novelist himself. Algren died in Sag Harbor, just before his induction into the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters, on the brink of a new and satisfying phase of his life that he could never enjoy.

The late Bouton, another man of the left, did not unwind in such a dismal way. A very good pitcher for a two-year period in the 1960s—for a time, he was an ace on a Yankees staff that included Whitey Ford—Bouton briefly had his own fan club and would have secured a place in Yankee lore for his outstanding pitching performances in the 1964 World Series against a vaunted St. Louis Cardinals team. The Yankees lost in seven games and their dynasty ended overnight; Bouton’s life as a pitching star was finished too. Arm trouble followed, as well as clashes with management: Bouton, by the late 1960s, was a favorite of the new, progressive breed of sportswriters who sought to write about more than just the box score. He spoke openly about his opposition to the Vietnam War and expressed support for the Civil Rights movement.

In 1969, Bouton turned 30, and headed west to the expansion Seattle Pilots. The rest was history: his account of that season, and the hijinks and drug use and poignant struggles of athletes on and off the field, became the grist of Ball Four, perhaps the best athletic memoir ever written. Nathanson delves deep into the writing process and Bouton’s own shortcomings: his ego, his strained marriage, and an odd attempt to airbrush his co-writer, Leonard Shecter, out of history as the decades wore on. Still, Bouton emerges as an important figure in not just the history of baseball but in sports writing itself, helping to demolish the mythos that hung around the professional leagues through the 1960s. Nathanson gives Bouton the biography he deserves.

This year, I also spent a lot more time reading Gore Vidal, as you’ll see from my list below. Vidal is one of those people I wish were living today; I can only imagine what witty, sweeping essays he’d write on Donald Trump, the Democratic Party, social media, and late Empire America. Vidal, who died in 2012, always had my admiration because of how multifaceted he was—he was a remarkably talented novelist, essayist, screenwriter, and playwright, blessed with a rare kind of range and professional success. He ran for office twice and, unlike Norman Mailer, he did it competitively. (Netting more than 40 percent of the vote in a 1960 congressional race in the Hudson Valley, Vidal claims Democratic Party bosses wanted him to seek a Senate seat in New York. He later ran and lost in California.) His critiques of American capitalism and foreign policy only prove truer with each passing year. As a novelist, he never got his due from the academy—I was surprised to learn he’d won hardly any literary awards—but he was an important writer, particularly for the risks he took to write about love between two men and later, in Myra Breckinridge, about a man who becomes a woman. Like Delany, Vidal was an elegant stylist and sensual writer, utterly unafraid of plumbing the essential and lovely murk that makes us human.

A second essayist I encountered this year was Vivian Gornick. Another native New Yorker, Gornick is now 85, still writing and publishing. I read her most recent collection of essays, a selection of literary criticism published this year—I particularly enjoyed her exegesis on Thomas Hardy, though I haven’t read Jude the Obscure—and one of her more well-known works of nonfiction, The Romance of American Communism. Gornick has all but renounced the work of oral history, which first came out in the 1970s. The child of American communists, Gornick is a skeptic of doctrinaire ideological movements, and in the introduction to the book she is self-critical, chastising her younger self for lurching too deep into psychoanalysis and purpling her prose. I somewhat agree, but the book remains a classic of oral history, and is deeply resonant as portrait of the men and women most captivated by the American brand of communism, which reached its apex in the 1930s. For those who had long left the movement, that time of belonging, solidarity, and purpose could not be replicated in ordinary life, even when they had repudiated the politics of their youth, learning of Stalin’s atrocities. They were men and women who believed revolution was as near as the next baseball season, that each day—a trip to the market, a ride on the subway—could be freighted with world-historical significance. At first, I felt sadness for these people, for how a movement could so thoroughly subsume their lives and never deliver upon its golden promise. But Gornick shows us that we are not meant to merely pity the American communists. They had what too many of we aimless, 21st century moderns lack: community. In the whirl of the politics, they rarely felt alone, infused with such delicious longing. You may want to go back, if just for a day, and feel what it is they felt.

There were two more excellent books of New York history I read: New York in the Fifties, a wonderful Greenwich Village memoir by the writer Dan Wakefield, who managed to befriend James Baldwin, Jack Kerouac, Joan Didion, and host of other 20th century luminaries, and The Hardhat Riot, an incisive history of both the 1970 hardhat riot in downtown Manhattan and a widescale examination of white working class grievance in the United States of America, from Richard Nixon to Donald Trump.

And, I should add, I finally discovered why Robert Stone is such an American original.

Now, without further ado, all the books I read in 2020, in chronological order.

All the Books

The Hike by Drew Magary

It Didn’t Happen Here: Why Socialism Failed in the United States by Seymour Martin Lipset and Gary Marks

Antisocial: Online Extremists, Techno-Utopians, and the Hijacking of the American Conversation by Andrew Marantz

Moonglow by Michael Chabon

The Spirit of Science Fiction by Roberto Bolaño

Nowhere Man by Aleksandar Hemon

Never a Lovely So Real: The Life and Work of Nelson Algren by Colin Asher

Apartment by Teddy Wayne

The Cactus League by Emily Nemens

Never Come Morning by Nelson Algren

The Body Politic by Brian Platzer

Empire City by Matt Gallagher

New Waves by Kevin Kwan

The Future Is History: How Totalitarianism Reclaimed Russia by Masha Gessen

Last Night in Montreal by Emily St. John Mandel

August by Callan Wink

Bouton: The Life of a Baseball Original by Mitchell Nathanson

The Names by Don DeLillo

Dog Soliders by Robert Stone

Hall of Mirrors by Robert Stone

Normal People by Sally Rooney

Bernie’s Brooklyn: How Growing Up in the New Deal City Shaped Bernie Sanders’ Politics by Theodore Hamm

Death in Her Hands by Ottessa Moshfegh

Asymmetry by Lisa Halliday

Parable of the Sower by Octavia Butler

Here We Are: My Friendship with Philip Roth by Benjamin Taylor

Point to Point Navigation by Gore Vidal

Dreaming War: Blood for Oil and the Cheney-Bush Junta by Gore Vidal

Mumbo Jumbo by Ishmael Reed

Something Happened by Joseph Heller

Baseball As I Have Known It by Fred Lieb

Myra Breckinridge by Gore Vidal

The Romance of American Communism by Vivian Gornick

New York in the Fifties by Dan Wakefield

The Silence by Don DeLillo

Real Life by Brandon Taylor

The Socialist Awakening: What’s Different Now About the Left by John. B Judis

Dhalgren by Samuel Delany

The Hardhat Riot: Nixon, New York City, and the Dawn of the White Working-Class Revolution by David Paul Kuhn

Unfinished Business: Note of a Chronic Re-reader by Vivian Gornick

The Soul of Yellow Folk by Wesley Yang

The Companions by Katie Flynn

Inside Story by Martin Amis

All His Breakable Things by Jiordan Castle