The Twenty-First Century Category Error

An aside on Bret Easton Ellis, the Drift, and Walter Kirn

In the latest edition of The Drift, the popular literary magazine founded in New York, is an intriguing essay about the novelist Bret Easton Ellis. The writer, Gabriel Jandali Appel, makes a study of Ellis’ career and his latest novel, The Shards, and also deconstructs his success as a podcaster. Appel argues, convincingly in my view, that not enough reviewers of The Shards noted its genesis on Ellis’ podcast and how the auditory medium informed what the written novel became. Appel also notes that Ellis, so disdainful of trauma narratives and the politics of sexual orientation, has very much written a painful bildungsroman of sorts about a young gay man in Los Angeles—Bret Easton Ellis. I found this same surprising vulnerability in The Shards, and I argued that it was his best novel since American Psycho.

There’s a sentence in Appel’s essay, though, that rankles me—one that, in the writer’s imagination, must have been something of a throwaway, or at least one that wasn’t intended to be a fulcrum of anything in particular. In a bid to elucidate Ellis’ podcast for those who may have heard of it but never heard it, Appel explained that the novelist, in both his literary heyday and the online culture wars of the 2010s, had a habit of verging close to “reactionary conservatism” and inviting on his show the most “annoying voices on Twitter.”

“Recent guests include Walter Kirn, Anna Khachiyan, and Amanda Milius, all of whom routinely attract attention by parroting right-wing talking points,” Appel writes, before hurrying to his next paragraph, a familiar quasi-indictment of Ellis’ politics, which have always been, somewhat intentionally, half-baked—Ellis professes to care not too deeply about American politics at all—and were mostly set down in White, his uneven 2019 essay collection. Ellis, who lives in Los Angeles, spent years mocking wealthy liberals who were terrified of Donald Trump’s rise and the shallow resistance-style politics that became dominant in the late 2010s. Ellis, to use the inelegant phrase, can be clearly sorted into the “anti-woke” camp, which makes him a hero to a segment of the internet and a heinous bigot to others. Much of the debate obscured Ellis’ singularity as a contemporary writer. That is always the danger when you branch out into other mediums.

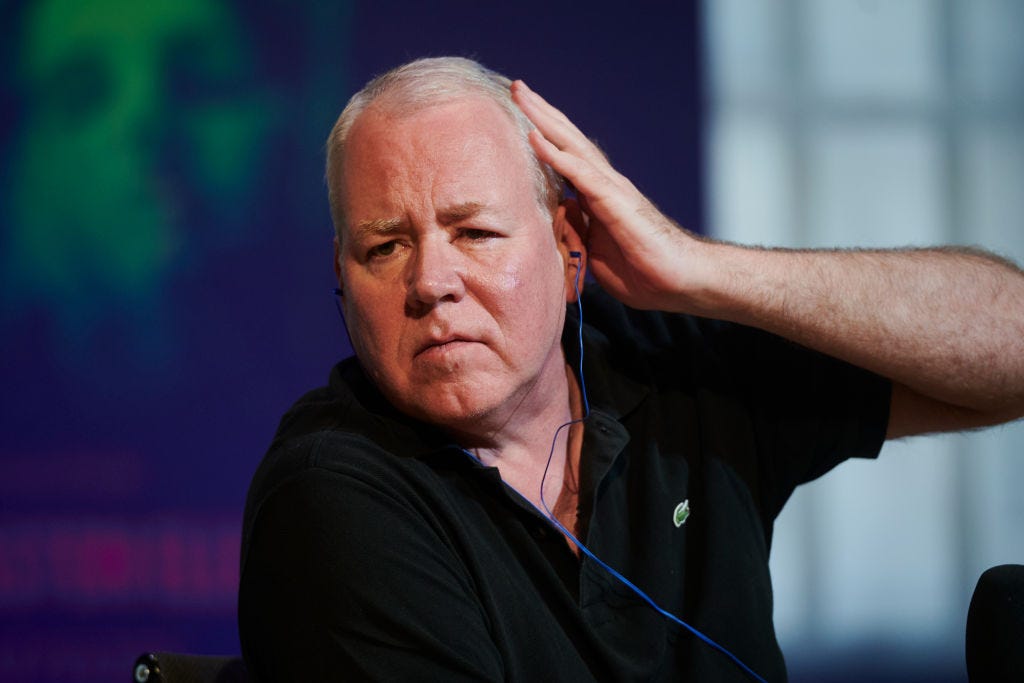

But it was the mention of Kirn that was particularly irksome, and called into question, for me at least, the entirety of Appel’s essay and even the project of The Drift itself. Walter Kirn’s sole mention in a journal of literature and ideas cannot be as a podcast guest who is “parroting right-wing talking points.” He is a novelist and an essayist, a former book critic for New York Magazine, a former columnist for Harper’s, and a former contributing editor at Time. He is the author of Up in the Air, a fabulous novel that was turned into a middling but well-regarded movie, and a very good memoir, Lost in the Meritocracy. Born in 1962, he is among the most talented writers of his generation. These days, in addition to writing books, Kirn pens occasional columns for Bari Weiss’ The Free Press and Compact Magazine, online publications that offer consistent criticism of left-liberal politics. He co-hosts a weekly podcast with Matt Taibbi, a one-time hero of the left who is now dismissed, by these same readers, as a reactionary. Weiss is reviled by most liberals, for reasons that are both understandable—she is a free speech advocate who has nevertheless spent much of her career vilifying those speaking up for Palestinian rights—and somewhat overheated. Compact is a mixed venture, publishing conservatives and economic populists. I’m not an inveterate reader of either, but have found worthy pieces in both, like Ethan Strauss’ recent feature on the Cavender twins and this study of Thomas Pynchon.

I’m also not a regular listener of Ellis’ podcast—I prefer the books—but I have listened to two of Kirn’s appearances, as well as read most of his recent published work. Since Kirn is not, explicitly, a left-liberal, he is swiftly categorized as someone who appears on Ellis’ podcast to parrot “right-wing” talking points, implying he has little agency of his own—he simply arrives to say whatever it is Rupert Murdoch has told him. Many readers here will ask, then, what is Kirn? Isn’t a guy who hangs with the “wrong” sort of folk or makes occasional appearances on Fox’s Gutfeld! clearly aligned with Team Red in our hyper-political age? Can’t a literary journal group him with Amanda Milius, someone who actually served in the Trump administration?

One answer is that MSNBC isn’t expected to know any better, but The Drift should. Literary publications exist, in theory, to be an escape hatch from hyper-politics, to excavate what cannot be so neatly sorted into a tiring binary. Kirn does not advocate for the election of Republicans. He does not endorse Donald Trump or any Republican rival, and I don’t know him to be privately supportive of any of these people, either. If you are going to insist on an ideological or formal grouping—or take his writings on politics and society and reduce them to something digestible—I would argue Kirn has a libertarian streak and an age-old skepticism of American elites, both in the corporate realm and the federal government. Kirn writes with a Twainian twinkle and is unafraid of flaying shibboleths. I don’t always agree with him, but that’s true of most people who challenge. Kirn grew up in the rural Midwest and went to Princeton, and his writing is informed by this duality, escaping what many, though not him, regard as a cultural backwater and “making it” among the elites who determine, one way or the other, the course of events. Kirn and Ellis, when they got together on the podcast, were mostly two Gen X novelists talking shop and swapping memories of a vanished world many younger writers wished they lived through. They recommended novels to each other. I read Joseph Heller’s follow-up to Catch-22, Something Happened, after listening to Ellis and Kirn talk in 2020.

Not every writer is going to be a left-liberal. Not every writer is going to have “good” politics. If the 2010s and 2020s orthodoxies reigned a century ago, a literary critic would have tossed together Father Coughlin, Robert Taft, and T.S. Eliot in the same sentence, dismissing all three as “annoying” figures who upheld or trafficked in right-wing politics. And Eliot, certainly, is not someone I would want to start a political club with; he was a monarchist and devout Anglo-Catholic. Ezra Pound, of course, was a fascist, and Louis-Ferdinand Céline, despite counting Philip Roth as an admirer, was a vile anti-Semite. For many decades, those who wrote about literature and created art themselves knew what to do with such men. Their politics were exposed and denounced. Their reputations waxed and waned. But it was understood they were, despite their inherent rottenness as people, consequential artists who had made inarguable contributions to the literature of the twentieth century. Since they were not politicians, even if they advocated for the fascists, it was plainly accepted that they were not going to be held to the same standards as a Republican senator from Ohio or a highly influential radio preacher. Eliot was in the business of Modernism, not excoriating the Labourites in Parliament. “The Waste Land” and “The Hollow Men” and “Prufrock” came first. They always would.

I hope for more from The Drift and the other literary upstarts of this neo-“little magazine” era that has been, largely, invigorating. In 2022, The Drift attracted a great deal of attention, and it drew many comparisons to the chic literary magazine of a prior era also founded by Harvard graduates, N+1. The N+1 generation, including Elif Batuman, Mark Greif, Chad Harbach, and Keith Gessen, went on to much acclaim, and the same may come for The Drift writers who include, among their ranks, Zain Khalid, one of the strongest novelists of his (and my own) generation. A greater question for The Drift will be how they eventually hope to distinguish themselves from N+1—or any other literary journal founded by New York or New York-adjacent Ivy League graduates. Will they develop a distinct aesthetic or, absent one, genuinely welcome the sort of people who will not conform to the politics or the moods of other well-educated, left-leaning people? Will they, or anyone else, subvert? Will they surprise? What will be their argument for a permanent place in the culture? I eagerly await what’s to come.

I'm not very familiar with the Drift, but I found n+1 to be mostly an intellectual ground zero for a generation of rich, privileged Brooklynites from Ivy League schools that gentrified that once-vibrant borough to insane smithereens and simultaneously created a "ideologically pure" political mindhive that ironically let themselves off the hook for offenses they were most guilty of, but loved ferociously, heinously calling everyone else out on. This group simultaneously near-destroyed all American subcultures and countercultures, and then moved on to infiltrate and destroy old-world cultural institutions throughout New York, and made a mockery of left spaces, who are now all totally run by smug yuppies from Brooklyn's laptop community. These are the people who think they're qualified to debate Adolph Reed on race and have become intrinsically anti-working class (and reactionary and puritan when you get down to it). They've made leftism and liberalism (and maybe even the idea of "culture") a dirty word for most working and middle class people. These are probably the worst people in recent US history. And I say that as someone who knows, and mostly likes on a human level, a lot of those people, and it makes me sad to see what they've devolved into on Twitter these last few years.

As far as the ignorant and continuing attacks against people who I'd actually consider on the actual left-liberal side of politics - but not going for some fake, dishonest purity - like Taibbi and Kirn, whose weekly podcast is full of truth, wisdom, warmth, humor, alongside a deep, profound literary knowledge - it's par for the course for rotten schmucks who invaded and destroyed New York's now-worst borough. They can't handle Taibbi and Kirn's honesty, and any criticism of - and especially bad news about - the new, post-liberal, post-left Democrats because it implicates them wholesale. I'd also argue that Anna Khachiyan has become one of New York's most important cultural commentators, because she sees through that empty cohort and knows how to deflate them thoroughly in a few sharp words, and she's turned archness into a high art form.

People should ask themselves why they're more mad about gentle, humorous and honest commentary from free-thinking liberal, literary types than actual conservatives? And what happened to open discourse and discussion and the exchange of ideas? Ten years ago Taibbi, Kirn and Khachiyan would have been NYC's intellectual heroes, and while they certainly are to the non-bodysnatched, Brooklyn wants to scare you away from even knowing what they say. (Even the Village Voice would be considered forbidden contraband now. We could certainly use a new Nat Hentoff, who'd also be considered dangerously "problematic" now.)

Kirn's Lost in the Meritocracy was one of my favourite reads of the past couple of years. The book really delves into the mindset of the modern-day literary/intellectual social climber that Kirn so refreshingly is honest about. To dismiss him as some kind of shallow political parrot because you disagree with his contemporary views is childish.

The first thing I ever wrote for my Substack a few months ago was partially about Kirn's book: https://salieriredemption.substack.com/p/the-dorky-social-climbers-of-the