The War on Genius

Literature and its systems

What is a novel, or any work of art, but the product of its time, of commerce? What is it but another colorful consumer unit, to be slid dutifully on a shelf or hawked through the internet? I’ve been mulling, of late, actions and reactions, the trope of the lone genius and the trope of systems. One held very long in the culture before being defenestrated, in academia at least, over the last several decades. The other is now dominant—at least, among those in the know, those who still analyze literature. In a systems conception, the genius of creation is disregarded and dismissed; no lone spark could truly emerge, no individual could labor, by herself, to write the novels, poems, or plays that endure across the ages, or even get remembered a decade after publication. Christian Lorentzen’s essay in Granta on Dan Sinykin’s otherwise acclaimed book, Big Fiction: How Conglomeration Changed the Publishing Industry and American Literature, strikes at the heart of this sociology of literature, which is well-intentioned, fascinating, and wrongheaded in an obvious enough way: it can say very little about what’s inside the actual books.

Sinykin, an assistant professor of English at Emory University, proposes reading literature through the publisher’s colophon, which is the little logo on the spine that tells you if the book came from W.W. Norton or Knopf or Penguin Random House or somewhere else. “Aesthetics double as strategy. Author and publishing house might be—often are—in tension, a tension that plays out between a book’s lines,” Sinykin writes. “I linger over books in these pages, reading them through the colophon’s portal, in light of the conglomerate era. I show how much we miss when we fall for the romance of individual genius. In novels, the conglomerate era finds its voice.”

Lorentzen calls this perspective “disgusting” and I’m inclined to agree, if I would prefer an adjective like “misguided” or “dispiriting.” Aesthetics is reduced to a sales strategy and the pleasure of reading itself, as Lorentzen argues, is equated to being duped by a marketing campaign. The professionals who work in book publishing are fine, industrious people, and a novel doesn’t merely exist because an individual conceives of it and tosses it into the world (though in the era of self-publishing, this can be true.) The conglomeration era, which began in earnest in the second half of the twentieth century—when smaller publishers began getting gobbled up by larger publishers, and corporations came to be dominant—did impact which books appeared in print and which didn’t, though it’s difficult to say a meaningful aesthetic revolution was brought about this way. The primary change in publishing, I’d argue, that has come in the new century is the diminishment of risk-taking on the side of literary fiction, the abandonment of the concept of a publishing house propping up and nurturing a young literary career, and the end of a certain trust that was invested in individual editors—Sonny Mehta, Gordon Lish, Gary Fisketjon, and a young Toni Morrison come to mind—to curate lists to their taste. This is not the focus of Sinykin’s survey, which takes a much cheerier look at the human beings who devised publicity strategies, retail models, and even book tours. “Conglomerate authorship” is what he writes about and what he believes in, ultimately. The authorship, he argues, we attribute to individual writers is merely a process diffused among the “conglomerate superorganism.”

We are all, in one sense, the products of systems; writers, in particular, are impacted by what is around them and can conform their works to the pressures of a market, the demands of an editor or an agent, or merely peer pressure. Certainly, novels centered around the ugliness of men are on the decline, and there are many reasons why, including a marketplace and editorial bureaucracy that has less regard for these stories than they once did. What this does not mean, though, is that authorship should be downplayed to such a degree that the existence of singular talent independent of a publishing machine’s input is regarded as nearly impossible. I quote John Pistelli, here, on Sinykin’s dismissal of that romantic genius: “just because you’re not doesn’t mean nobody is!”

There’s a curious aside from Sinykin on Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow. The postmodern epic, which I first read in college and for a time was entranced by, was once a favorite of Sinykin’s. “Carrying the book made me feel unique, and reading it made me feel smarter than everyone else, but it was more than that. The language was exhilarating, the sensibility hilarious, the politics strange and enchanting,” he writes. It was, for a time, “a lesson in how to distinguish myself from others based on my taste; a fondness for liberatory politics; and a love of challenging prose, lush language.” This, though, would come to cause him a kind of anguish, since his “pretension to uniqueness, through Pynchon in particular, was repeated by cocky young white men across the United States. I was a type and played to it. In graduate school I met iterations of myself, again and again.” Indeed, in graduate English programs throughout America, there were students, men in particular, drawn to a novel that won the National Book Award and was instantly deemed a modern classic. There were those, even, who were attracted to the cult of Pynchon himself, a buck-toothed Long Islander who never allowed himself to be photographed after the 1950s, plunged headfirst into the 1960s counterculture (he even met Brian Wilson), and once made a cameo on The Simpsons. For whatever reason, as a fellow white male who cultivated a great love of literature in my collegiate years, I never felt any anxiety or shame if I met others who liked the books I did. In fact, I was excited. Literature can be a lonely pursuit, after all, and if community can be found, all the better. Sinykin’s implication, though, is that the “cocky young white men” who claimed Gravity’s Rainbow were a problem that needed to be solved. And the problem did get solved, though not in the way a liberal college professor might have wanted. These men now turn to Andrew Tate, Jordan Peterson, and Reddit. Why cling to a dense, quasi-amorphous, and polyphonic World War II novel when you can stream YouTube eight hours a day?

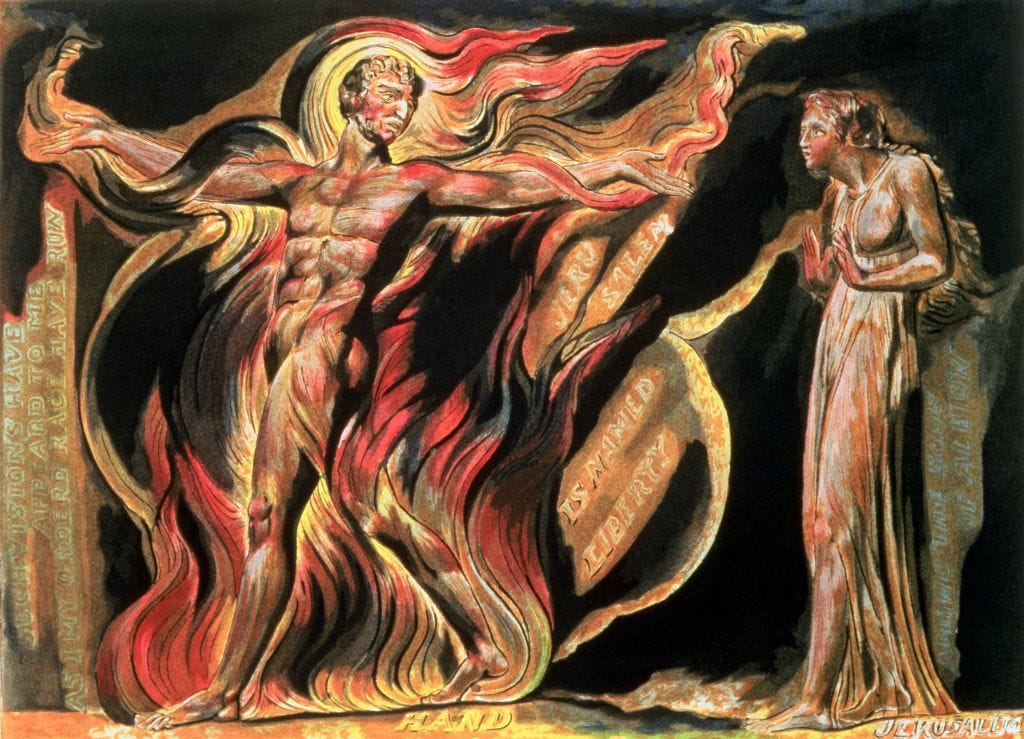

Making a defense of the novel or even the plausibility of genius flowering in such a form can make you, in this new world, an alien or even embarrassing creature. Genius? How gauche! Read the colophon! Never mind that Pynchon, for one, is a genius, and that is why enough readers stick with him still. Publishing houses, publicists, agents, and even editors do not create works of literature. The creator does; the creator logs thousands of hours at the laptop or the notepad or, if they’re feeling ambitious and antediluvian, the typewriter, and this process, for all the ways we quantify and commoditize everything in American life, remains mysterious, even in our budding artificial intelligence age. A writer sits and thinks and words, somehow, appear. Ideas can be kismet. Language percolates in the shadow of a thought, and these shadows do not have much to do with marketing directors. The attractions, obsessions, and even hatreds of the individual make what a novel is, and pieces of the creator, unpredictably, lie everywhere. Writing is communion—there is no god or world-spirit, necessarily, telling you what to do, no magic current bearing you aloft, but there is the alchemy between brain and digits, that light-speed spark which remains difficult to explicate to anyone. And there are images. How do words render images? Where do the images of the mind begin, these counter-worlds, these dreams? A full book can arrive in a month or a decade. A great book is rarely written. No conglomerate superorganism can make it so—it’s up to that lone ranger, the author, digging in for long days and nights, groping toward beauty. It’s up to the author to care and believe in it. If you aren’t trying to write a great book, one that crackles with genius, what’s the point?

I loved Lorentzen’s article. His main target, to my mind, wasn’t necessarily Sinykin’s argument but rather his approach, an approach that you rightly point out has become dominant in English departments. This is the material, or the sociological, or the cultural approach, the approach that looks to the book as a product which can reveal something about the society that produced it, rather than regarding the book on its own terms as an aesthetic object to be analyzed.

Both approaches have merit, but the issue is that Sinykin’s mode has become so, dare I say, hegemonic in English departments that there’s barely any room left for close reading of the text, as well as analysis of style, form, and language. I was an English major and trying to explain this to non English majors was incredibly difficult. I’d tell them that we don’t really read books as English majors, but we talk about postcolonialism, Marxism, feminism, psychoanalysis…Usually they’d say, oh that sounds cool, and I’d say, well, actually I just want to read books and talk about them, but apparently there’s nowhere to do that anymore in the university! I’m exaggerating a bit, but anyone who has studied English knows what I’m talking about. The best way to deeply engage with novels at the university is probably via a Comp Lit major or by studying a foreign language. Or, outside of academia, via the local library and substack.

Yes to this article, yes in every flavour and colour scheme. Cannot get on board with this strange and oxymoronic idea that there's something liberating in saying 'I, unlike the other termites, know full well that I am a termite'.

For god's sake, the sin of the age is its almost total disregard for the dignity of the individual. I'm perfectly aware of the dense weft of social influences even unto the subvocals I get in my head when reading, but we've known this since forever. Aristotle knew it! This really doesn't mean that one isn't also a human being.

In the end, I love reading because I do, because there is something about the communion of voice to mind, the feeling of the universe being opened a little more*. That's enough for me.

(*NB not a clumsy plagiarism effort, surely one of the better known lines of the American novel in the last seventy years. Just a disclaimer.)