R.I.P. Sportsfork

On the de facto deaths of Sports Illustrated and Pitchfork

Sports Illustrated and Pitchfork are effectively no more. The former might actually be dead—mass layoffs resulting from a dubious financial arrangement—and the latter will exist, in some diminished form, merged into GQ. The news disquieted me in different ways, and it occurred to me I’m one of the rarer people who, at one time, cared equally about what each publication had to say. For one place, my feelings were uncomplicated, my reverence plain. For the other, resentment and fascination blended, and I was never sure what I wanted out of its future.

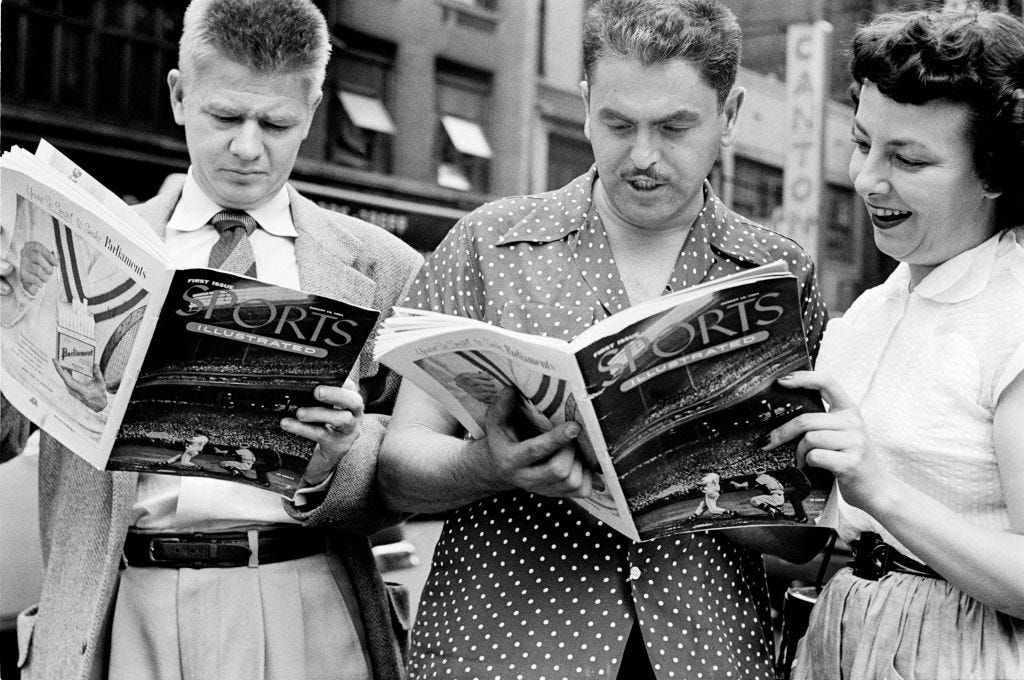

I’ll begin with reverence. As a midway millenial—born somewhere between the older and younger cohort of my generation—I caught the last of the old macroculture, and could marinate in some of the twentieth century’s delicious exhaust fumes. I remember when the internet was ancillary to everyday life. I remember when social media didn’t exist and when it was a mostly irrelevant curiosity. I remember when cable television, print newspapers, and print magazines absolutely mattered, and when cultural life was organized around appointments. The new South Park on Wednesday nights, American Idol at the start of the week, Pardon the Interruption every weeknight at 5:30, with Around the Horn as the lead-in. And a Sports Illustrated tied in with the mail bundle my mother plopped on our cramped dining room table, the magazine passed along to me without hesitation.

A weekly news magazine, merging sports and literature, was once the final word. The baseball preview, Frank Deford, Dr. Z, Faces in the Crowd, Reilly’s shtick in the back, would your team or your player end up on the cover? My favorite covers were those that seemed declarative enough to be a siren call, the start of history: WORLD SERIES. That kind of gravity is what the social media age, to a large extent, has annihilated. The waiting, the wanting, the hoping—and then you beheld, in your hands, the glorious photographs and the attendant prose, and you hoped you didn’t drink it all in too fast before the next issue arrived.

I read Sports Illustrated into college, and my attention naturally drifted elsewhere. I wasn’t watching SportsCenter anymore, either. My father kept up a subscription and I’d read an issue whenever I visited my parents; he was sure, always, to preserve an issue with an article about baseball. For years, Sports Illustrated had been buffeted by the same savage currents that have come for all print newspapers and magazines. The ad market evaporated, the news cycle continually sped up, and the attention-robbing distractions multiplied. Sports coverage, in particular, now revolves around seeding gambling addictions and chasing micro-scoops on Twitter/X. There is still a market for good writing about sports—Grantland was popular before getting shut down—and my hope is that a revived Sports Illustrated or a different magazine can carry on this tradition without being weighted down by a bizarre fiscal structure. A subscription-driven, Defector-style model might work, and it would be wise to keep a print component of some kind. Prestige fades when print dies and a certain number of smaller magazines, over the last few years, have proven themselves quite durable. There’s a path forward to be found.

One of the surprising aspects of the current internet is that it has not eroded long-form writing and reporting. Sports Illustrated needs a workable business model, but the product is not in doubt: there are enough people who will read several thousand words about a topic, particularly if these words are interesting enough. The BuzzFeed era, thankfully past, popularized the mistaken notion that only bite-sized content could succeed. In fact, it’s the larger, more ambitious pieces that attract the most traffic. If you are aiming for some degree of permanence, you are bound to do well. Algorithms have not sapped the longing for excellent writing.

What they have done, unfortunately, is weakened the desire for discernment. The new internet, at least among the professional class, has bred a generation of proud philistines. The poptimist bent in music criticism and appreciation is an outgrowth of this; it is no longer a mark of character or acumen, in certain circles, to think deeply about what art might be worth or how it furthers the culture. I feel, at the very minimum, mixed feelings about the probable demise of Pitchfork. If I was too young for the golden era of Sports Illustrated, I was right on time for Pitchfork’s hegemony. Gen Z might not understand how dominant Pitchfork once was in the worlds of alternative and independent music. Rolling Stone, with few exceptions, never made or broke bands. Pitchfork did. From the early 2000s until around 2010 or so, a Pitchfork review could be the difference between fame, infamy, or irrelevance. Rating albums to a decimal degree—is it a 7.4 or a 7.7???—was brilliant and deranged, and invited endless intrigue. If Pitchfork reviled you, it could be as scathing and amoral as the old Gawker. There was the mostly harmless indie pop band that got signed to a major label, released their first album, and got a 3.3: which, in this context, was literally two frowning pugs. The band’s budding career was effectively over. Pitchfork was happy to punch up, too, handing out a zero to Liz Phair and deriding various Weezer releases. And when Pitchfork decided to champion a band, they were headed to the indie stratosphere. Clap Your Hands Say Yeah, Broken Social Scene, and Deerhunter were all Pitchfork favorites that found fast success, along with bands like Vampire Weekend and Animal Collective that achieved, in various forms, crossover fame.

When I was deepest into new music, in my late teens and early twenties, Pitchfork stood atop the mountain. Indie culture was at its peak. Brooklyn was rapidly gentrifying but was cheap and outlaw enough, depending on where you were, to play host to a remarkable array of popular DIY (and often illegal) venues. If you’re of a certain age and predisposition, Market Hotel, Death By Audio, Silent Barn, Shea Stadium (not the demolished Mets ballpark), Monster Island, and Glasslands will have some meaning to you. They, along with Pitchfork and the smaller blogs, belonged to the mesoculture, that space between the mainstream and the burgeoning digital underground. It was, in retrospect, an exciting moment, if the pretenses proved grating at the time. My close college friends played in a rock band and ended up performing at many of these venues. Through them, I was more of a participant in the 2000s indie culture than I realized then, and hung out a loft space that would prove worthy, in later years, of a New York Magazine oral history.

What I didn’t like about Pitchfork was that they shut out too many deserving rock bands and had, at their peak, too few rivals. (My friend, who remains a rock musician, quipped recently that he had outlasted Pitchfork.) As the critic Wayne Robins also noted, they often suppressed the original voices of individual critics. The problem, overall, wasn’t a website dedicated to a blend of thoughtful or overly scathing criticism of rock and other kinds of music. The problem was that there weren’t more Pitchforks, as well as other alternative newspapers and magazines to offer genuine counterweights. Rolling Stone competed with Creem, Spin, and Crawdaddy. Pitchfork rose to power as print newspapers and magazines were beginning their long contraction, with cultural mainstays like the Village Voice already bleeding staff. The internet, before the onset of social media and streaming, was a boon to Pitchfork. But what crushed print would doom Pitchfork, too. A music review website was nothing against Spotify and it could not, in a world of Facebook and Google, command a sustainable digital ad rate.

Who needs music criticism, anyway, now that the algorithms can do the work for us? One misguided journalist seemed to take a mild delight in the death of the “gatekeeper” concept. What I’ll first say to the many writers and critics who are mourning the de facto death of Pitchfork is the plight of the working musician today is far worse. The musician has suffered most in the last twenty years, their work first devalued by illegal downloads, then iTunes, and finally the streaming economy, which tricked a generation of human beings into believing the entire history and present of music should be available for the price of one LP (or less) per month. My hope, as Spotify teeters on financial ruin, is that a better model replaces it.

On the idea of algorithms replacing critics, consider how hard it is to figure out what good music is getting released today. Algorithms do not sort through dross; they merely reflect back to you what you already like. I don’t want a culture forever looking backward. A streamer won’t make new discoveries and it won’t make an argument for anything. It is derivative and inert, suited for the passive. Pitchfork, in its later years, became less interesting, too happy to validate whatever was climbing to the top of the charts and streams. In 2021, Pitchfork cravenly rescored old albums their critics had readily dismissed in the past—or praised too heartily. Grimes came in for a beating, mostly because, it seemed, she had been dating Elon Musk. Foxygen suffered because 1960s-derived rock was not as cool as laptop music. Interpol’s Turn on the Bright Lights had to be downgraded too, though the irony here is that, with the post-2021 indie sleaze revival in full swing, a future incarnation of Pitchfork might have to turn around and raise the album to a 9 again. (Room on Fire, at least, got boosted.) How often do critics post tortured apologies for old reviews? You could sense, in the end, Pitchfork just wanted to be liked. It wanted to coexist comfortably with the algorithms, the dominant tastes. In the whirl of re-ratings and recriminations, it hoped to matter again. Like Sports Illustrated, it does deserve to live on, and it will need paying subscribers to thrive in the new world. Some of the laid off critics might even consider starting a Substack. Make it new, and make it good. The audience may just show up.

Great write-up! "What I didn’t like about Pitchfork was that they shut out too many deserving rock bands and had, at their peak, too few rivals." Couldn't have said it better.

Excellent piece - and the only write-up of Pitchfork's demise that delves into what I think is an often-overlooked aspect of the decline of a lot of media shops: mainly, their rush to hold the same opinions and tastes as everyone else. What you refer to as "Pitchfork just wanted to be liked." Yes, handing out a zero to a Liz Phair album is obnoxious. But that obnoxiousness, whether or not it's someone's cup of tea, was a big part of Pitchfork's identity. You get rid of that and you're basically one of the hundreds of indistinguishable music blogs/websites tripping over themselves to fawn over Taylor Swift. At that point, what does it matter if I read Pitchfork or one of the countless other sites that spout the same opinions and have the same tastes?